The Invisible War: Inside the electronic warfare arms race that could shape course of war in Ukraine

Ukrainian military practice flying drones at night using thermal vision in Lviv Oblast on May 11, 2023. (Paula Bronstein /Getty Images)

When Ukraine received Excalibur artillery shells in March 2022 from the U.S. shortly after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, it was immediately the military’s weapon of choice.

Thanks to their GPS navigation system, these expensive munitions had a high-precision flight trajectory and could be used in urban combat.

Fast forward one year to March 2023 and the Excaliburs suddenly started missing their targets.

Russian electronic jamming, which overloads a receiver with noise or false information, was blocking the artillery shells’ GPS, causing the ammunition to miss its mark.

Similar issues began to occur in April 2023 almost immediately following the delivery of Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAM) guided aerial bombs and Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System GMLRS long-range missiles, which can be used with U.S-made High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS).

To make matters even worse, Russian soldiers were also jamming communication with Ukrainian drones, causing both reconnaissance and strike drones to crash, land on the spot, or in the best case, return to base.

In a war where both sides have relied heavily on the use of all types of drones — so much so that this war has been dubbed the “War of Drones” — Russia’s jamming capabilities have presented a major challenge on the front lines.

Electronic jamming is just one example of electronic warfare (EW), an entire set of invisible weapons that use electronic means on air, sea, land, or space to obstruct and mislead enemy communications and electronically-guided weapons systems.

EW systems vary in size and form, from pocket-sized devices to truck-mounted radar arrays and transceivers. They can be divided into several types, which differ in their purpose, including:

- Devices for countering and suppressing the enemy's radio-electronic means (radio and satellite communications, radars, etc.), as well as guided missiles and kamikaze drones.

- Devices for protecting personnel, military facilities, and equipment from the influence of enemy EW.

- Means for detecting coordinates and information about the location and actions of the enemy thanks to the intercepted signals of communication channels.

Depending on their operational range, EW can be divided into: tactical (up to 50 kilometers), operational-tactical (up to 500 kilometers), and strategic (over 500 kilometers).

On the closest-range tactical level, there is also "trench EW" — radio-electronic devices that work up to 10 kilometers and are designed to cover small tactical groups from reconnaissance and FPV (first-person view) drones.

Russia has traditionally invested heavily in growing its EW capabilities, with development placed into overdrive as the full-scale war against Ukraine continues. As the front lines have stabilized, its military has been able to place large numbers of its EW assets where they can have the greatest effect.

In his controversial opinion piece for the Economist published in November 2023, now-former Commander-in-Chief Valerii Zaluzhnyi wrote that Russia’s superiority in the number of its EW assets was one of the main threats to the war turning positional, which is not in Ukraine’s favor.

"Along the Kupiansk and Bakhmut axes, the enemy has effectively created a tiered system of electronic warfare, the elements of which constantly change their location," Zaluzhnyi wrote.

Acknowledging the importance of achieving parity in EW, the Ukrainian government is also working to speed up the process to get new technologies onto the battlefield.

Russia’s dominance in electronic warfare

Russia's density of the EW systems it can deploy is thanks to years of investment.

Ukraine and Russia began the conflict with differing starting capabilities. Nearly 65% of the Ukrainian Armed Forces' jamming stations were produced during the Soviet Union.

Russia on the other hand has been particularly active in developing its own EW systems since 2009, partly as its response to NATO’s network-centric systems and as EW troops have become a separate branch of the Russian armed forces.

A separate branch of the Russian military dedicated to EW has existed since 1991, developing over 60 different EW device models with various purposes and ranges. This has allowed the country to do away with its outdated equipment almost entirely, Valery Zaluzhnyi mentions.

Russian forces' use of EW in Ukraine goes far back before the launch of the full-scale invasion.

During the 2014-2022 war in eastern Ukraine, Moscow sent propaganda and fake orders to Ukrainian troops and civilians by spoofing the local cellular network, probably using the RB-341B Layer 3 system, according to volunteer investigative initiative InformNapalm.

It also helped them find the location of the Ukrainian personnel who at that time mainly used mobile phones to ensure communication.

At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the imbalance in EW between the two sides had a minor impact.

Now, with the front line largely static amid positional fighting, Russia has positioned one large EW system along every 10 kilometers of the front line, the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) reported.

Russia’s Shipovnik-Aero EW complex, according to the RUSI report, is particularly effective at countering Ukrainian drone operations. The system has a range of 10 kilometers and can take control of a drone while simultaneously obtaining the coordinates of the operator's location with an accuracy of one meter.

It can then relay this information to an artillery battery that now knows where to aim to inflict the most damage.

At least three out of five Russian electronic warfare brigades, whose operators gained experience in Syria, are involved in the war in Ukraine, wrote Bryan Clark, director of the Institute’s Center for Defense Concepts and Technology. This is not taking into account the specially trained company in other brigades.

Capable of operating at a distance of up to 300 kilometers, the Krasukha-4 is one of Russia's most advanced electronic warfare (EW) systems and the central element of its strategic EW system. The system is designed mainly for jamming airborne or satellite fire control radars.

Krasukha-4, which was too powerful and bulky to be useful during Russia’s initial offensive on Kyiv, is now being used in Donbas and southern Ukraine. It is able to disorient AIM-120 AMRAAM homing missiles and Patriot air defense radar stations and interfere with Ukrainian lines of communication, preventing Ukrainian forces from detecting Russian artillery points.

There are no developments of a similar level in Ukraine since strategic longer-range EW was not a priority direction for the Ukrainian military-industrial complex before the full-scale invasion.

Chinks in the armor

Despite Russia’s abilities on the battlefield to deploy EW, not everyone is convinced they are as superior as they appear.

"Russia has made this into a separate branch of the military and boasts of significant developments, but I constantly say that Russian EW is overrated," Anatoliy Khrapchynsky, military aviation expert and deputy general director of anti-drone rifle and EW company Piranha-tech, told the Kyiv Independent.

"Most of their developments are related to working in the areas known during Soviet times — navigation, suppression of radio signals, interception of communication frequencies, etc."

Khrapchynsky pointed to the shooting down of four Russian aircraft in May 2023 as examples of where Russian electronic warfare has failed.

In that downing, above Russia’s Bryansk Oblast, two SU-34 and SU-35 fighter jets and two Mi-8MTPR-1 escort helicopters were destroyed.

EW systems designed to protect aircraft from anti-air missiles with radar targeting can be installed on a fighter, but they are quite heavy, limiting the overall armaments the plane can be equipped with.

As such, it is helicopters that are usually equipped with powerful EW equipment and ordered to fly 10-30 kilometers from the front line to create obstacles for enemy radars in the bombing area until the aircraft completes its mission.

Russia’s Mi-8MTPR-1s are equipped with “Rychag-AV” stations, which were supposed to protect the fighters from being detected by Ukrainian air defense and their radar systems.

A similar situation was repeated with fighters at the front in the Avdiivka area. In five days in February 2024, the Defense Forces of Ukraine destroyed seven Su-34 and Su-35 fighters.

However, it is currently unknown whether Russians used escort helicopters Mi-8MTPR-1, of which they have less than 20, or whether the Khibiny EW system. It is attached to a fighter jet which, according to the Russian media, was specially modernized for the war in Ukraine.

Ukraine’s little-known, powerful EW system

Meanwhile, on a national level, Ukraine is developing a system designed to help it cope with constant Russian missile and drone strikes.

Named Pokrova, little is known about the system, but it appears capable of both suppressing Russian satellite navigation systems like GLONASS and spoofing them by replacing genuine signals with false ones.

It is also likely able to mislead missiles into believing they are somewhere where they are not, according to the Ukrainian military journal Defense Express.

Missiles have several guidance systems: a programmed trajectory, GPS control points, and a radar surface measurement system that compares the terrain with loaded data.

EW can create certain locations where the missile loses its sense of presence and cannot understand its coordinates.

As a result of suppressing these systems, the missile loses accuracy and fails to reach its target.

Pokrova was first publicly mentioned by Zaluzhnyi in his November 2023 piece for the Economist. Following Russia’s Jan. 13 large-scale missile attack, the Head of the EW Department of the General Staff of Ukraine’s Armed Forces Colonel Andriy Starykov said on air that the Pokrova system “is already working.”

Of the over 40 missiles launched by Moscow in the Jan. 13 attack, the Ukrainian Air Force said that more than 20 had failed to reach their targets.

At least some of them were diverted by electronic interception methods, according to Ukraine’s Air Force.

"Over two years, the Air Forces were able to build a tiered defense that directly incorporated electronic warfare means, which includes both air defense and electronic countermeasures,” Khrapchynsky said.

“Due to the construction of the Pokrova, Ukraine managed to reduce the accuracy of spoofed missiles by 40%. This technology has matured for a long time, but the enemy is changing tactics and combining strikes, using more and more ballistic missiles.”

Khrapchynskyi also added that in order to more effectively protect Ukrainian cities and infrastructure from enemy long-range missiles and drones, it is necessary to build systems of low-altitude radar fields that could see such airborne targets even at a height below 500 meters.

From volunteer orders to state contracts

The technology race continues at the front line. Special tools for silencing enemy radio signals and conducting reconnaissance are needed for every unit.

Andriy Znaichenko, director of military tech company Kvertus, broadly categorizes electronic warfare systems into "large" and "small" EW.

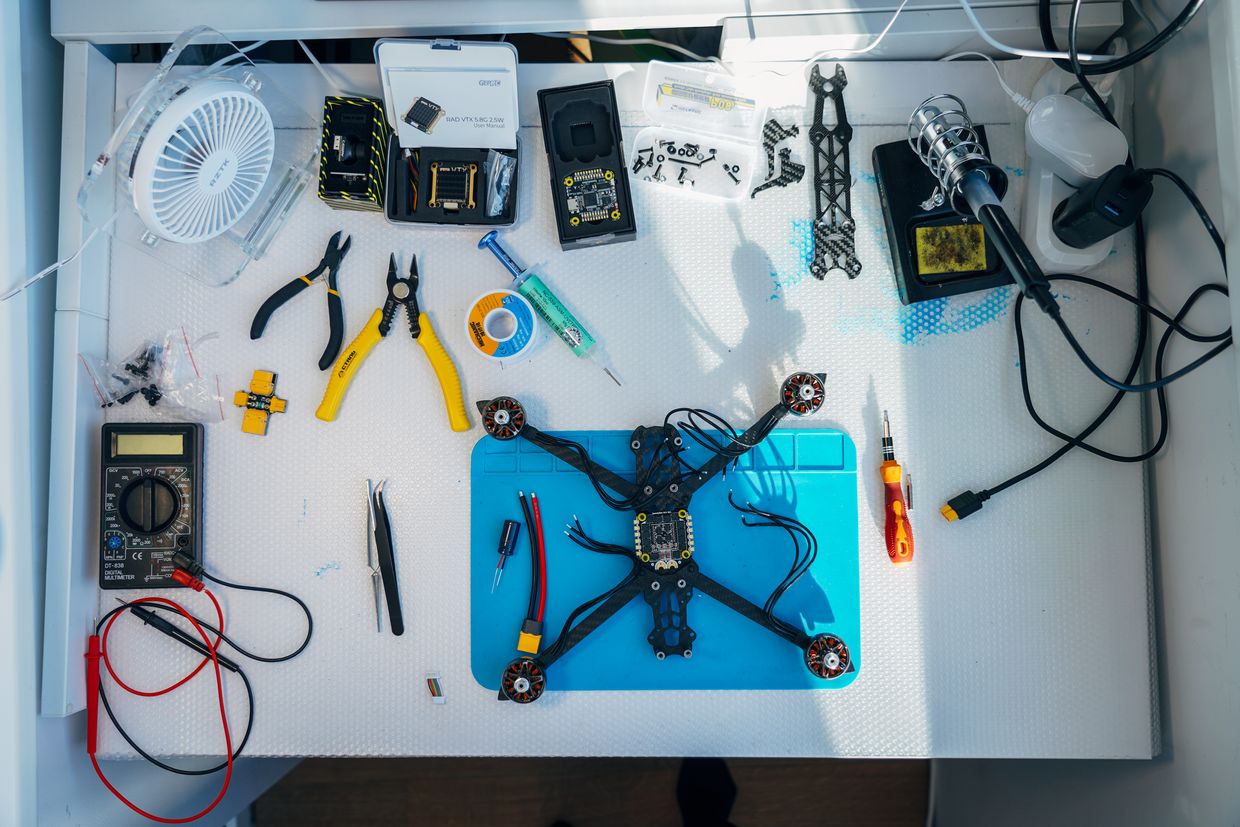

The former includes complex systems with several special vehicles that detect radio emissions over large areas. The latter consists of portable stations, anti-drone rifles, and backpacks with radio frequency jamming capabilities to protect against kamikaze FPV drones.

"If we talk about 'large' EW systems, the Russians indeed have an advantage there. They have more of them. In the 'small' systems, we are making decisions that are no worse, despite the fact that their industry is scaling up its volumes,” he said.

In Russia, mass production mainly comes from the state's military-industrial complex and associated firms.

"Although their electronic warfare is not as strong as they would like it to seem, the Russians have one advantage—they have more quantity," Khrapchynsky said.

Meanwhile, in Ukraine, developments are driven by private research companies, which face several problems, particularly in collaborating with the government.

Until 2022, obtaining certification and orders from the Defense Ministry took from two to four years. The procedure now takes a few months.

Znaichenko’s company specializes in the production of protection systems against unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), as well as electronic warfare and intelligence systems. He says that over the past year, his company has increased its production capacity several times.

"At the beginning of the invasion, we made dozens of anti-drone rifles, which were mainly ordered by volunteers. Last year there were hundreds, and now there are thousands of devices, mostly through government contracts," he said.

However, not all problems have been resolved. All Ukrainian companies depend on a flow of imported parts, particularly from China, often competing with Russian demand.

"We try to purchase quality parts (cables, connectors, feeders) from American, European, Taiwanese, and Korean sources, but in some cases, we cannot do so without China," said Khrapchynsky.

"At the same time, there still exists a paradoxical situation where I can buy five Chinese anti-drone rifles, two of which will not work, and import them without paying tax. Meanwhile, when a Ukrainian company purchases components, it pays taxes."

The Government of Ukraine has developed several laws to promote the modernization of the military, including the import of anti-drone guns and UAVs without duties and taxes when equipment is supplied under a government contract.

This was done so that middlemen don't receive excess profits. But it puts a tax burden on companies if they order components, rather than completed products, for a future contract or if the equipment is purchased by volunteers.

Another challenge is the need for more skilled personnel. Most military tech companies have open positions for hardware engineers and radio engineers.

However, the development of Ukrainian companies could benefit the industry even after the war.

Znaichenko, who recently returned from an arms exhibition in the Middle East, claims that the developments of Ukrainian companies have surpassed the vast majority of foreign ones and have export potential.

"Our main advantage is that Ukrainian technology is tested in practice. Little has changed in radio reconnaissance, the devices work on almost the same principles and frequencies as before,” he said.

“Instead, in the interception of drones, 95% of what I see from colleagues abroad remains at the level of 2020.”

“Some of their solutions propose jamming frequencies in drones that have not been used in the war for two to three years. It will take them several years to catch up with us."