With a web of drones and infiltrating infantry, Russian troops overrun Kupiansk

Ambush drones, urban infiltration, and a daring Russian river crossing now puts the major Kharkiv Oblast city under threat of a second Russian occupation.

Ukrainian soldiers remove camouflage netting from a 152mm howitzer on positions near Kupiansk in Kharkiv Oblast on Sept. 24, 2025. (Francis Farrell/The Kyiv Independent)

Editor’s Note: In accordance with the security protocols of the Ukrainian military, soldiers featured in this story are identified by first names and call signs only.

KHARKIV OBLAST- Dug deep within walls of black soil in the rolling hills of northeastern Ukraine, what was once the undisputed god of war can no longer afford to rise above ground for long.

With an 8-meter barrel designed by Soviet engineers for long-range and accuracy, the Ukrainian Giatsint towed howitzer is pointed to the skies as artillerymen of Ukraine's 15th National Guard Brigade, better known as Kara-Dag, receive the morning's first fire mission.

With knowledge and teamwork honed in some of the toughest parts of the front line, from the southern counteroffensive in 2023 to the fighting around Pokrovsk and Kurakhove, the crew fire three huge 152mm shells in rapid succession, each shot shaking the earth-and-wood position custom-made to conceal and protect their gun from enemy drones.

Their target: Russian infantrymen spotted near the shore of the Oskil River, looking to cross to the western side and join the rush of bodies upon the city of Kupiansk.

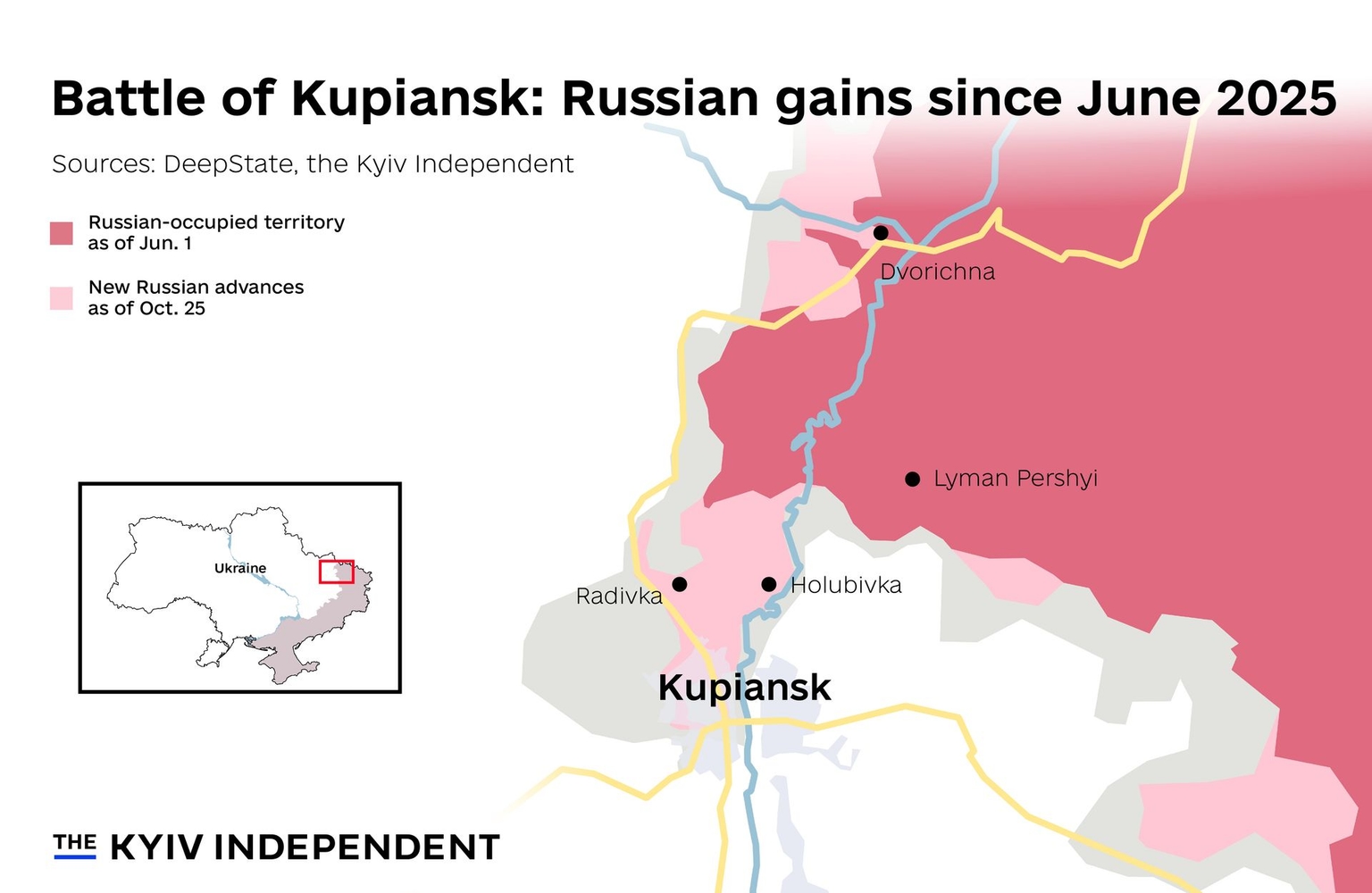

Liberated by Ukrainian forces in the lightning counteroffensive of September 2022, Kupiansk was stuck in the front-line zone for three years of fighting, as Russian forces entrenched themselves in the forests north and east of the city.

Now, Russian troops are back in Kupiansk, in what is likely to be the largest Ukrainian city to be occupied a second time by Russia after being liberated.

As is the case across the front line, Russia attacks here mostly with small infantry groups, backed by an ever-thickening carpet of drones in the air.

In the thinning but still dense autumn foliage, these tactics leave Ukrainian drone and artillery teams chasing shadows.

"They ran away in all directions," said Andrii "Mazhor," chief of staff of the brigade's artillery division, on the result of the fire mission.

Breach in the north

The Kara-Dag Brigade's sector lies directly north of Kupiansk, where Russian forces have secured a foothold on the western bank of the Oskil.

At the command point of the artillery division, the role of one howitzer team can be seen in the context of the brigade's dense array of reconnaissance and strike assets: the large split-screen displays show live feeds from Mavic-style and fixed-wing reconnaissance drones, first-person view (FPV) and heavy bomber strike drones, as well as unmanned ground vehicles.

Every now and then, a new user enters the video chat: the intercepted signal of a Russian drone, giving Ukrainian teams on the ground fair warning of the threat in the sky.

Ever since Russian offensive pressure on Kupiansk started mounting in 2023, the greater threat seemed to be the recapture of territory on the eastern side of the river, which Russian forces reached in an offensive push in 2024.

But after an overstretched Ukrainian military left part of the river north of Kupiansk, near the village of Dvorichna, badly undefended, Moscow took the opportunity to cross and establish a bridgehead on the other side.

Over summer and autumn of 2025, while attention remained mostly on the fighting in Donetsk Oblast, Russian forces steadily inched southward along the western bank, reaching and breaching the outskirts of Kupiansk in August.

As Yurii Fedorenko, commander of the Achilles Strike Drone Regiment, revealed in September, several underground pipes running under the Oskil River were also used by Russian soldiers to enter Kupiansk, in a practice already refined elsewhere, such as in Avdiivka and Sudzha in Kursk Oblast.

Now that the pipes have been destroyed, the river must once again be crossed on the surface. On a drone feed, a small inflatable boat is spotted tied to the riverbank.

Given this terrain, the Kara Dag Brigade's mission is an unusual one: rather than repelling direct attacks, they guard the corridor entering Kupiansk from the north, shaping a deadly gauntlet that Russian troops must pass through to make it into the city.

"Compared to other sectors, I haven't seen soldiers of the Russian Federation die as pointlessly as here," said Mazhor.

"I haven't seen a single wounded soldier getting evacuated."

Urban havoc

In a small farming village somewhere between Kharkiv and Kupiansk, the air is laced with the smoke of soldering irons as technicians work around the clock to keep drones flowing to the front line.

This is the beating heart of Black Wing, the specialized drone unit of Ukraine's 116th Mechanized Brigade, fighting in and around Kupiansk itself.

During a visit to the workshop, the Kyiv Independent spoke with drone operators who had just rotated off their positions.

While much attention is often given to Ukraine's larger separate drone units, most of which are in the Unmanned Systems Forces, it is units like Black Wing, attached to Ukraine's bread-and-butter brigades, that often shoulder much of the burden for holding the line.

With Russian forces often targeting sectors of the front line defended by weaker units, the need for every brigade to boost its drone component — often without much support from the state — is crucial.

"We have a situation where, for example, there can be 2-3 brigades alongside each other, but they are not equipped and manned on the same level," said Andrii "Tioma," 30, an FPV pilot in the 116th Brigade.

"Maybe the overall picture can seem okay at first, but the Russians see a weak spot with weaker personnel or fewer fire assets, and target that area."

On the screens of Black Wing's command post, Russian soldiers can be seen moving around the central square of Kupiansk. FPV drones are seen flying into the windows of multi-story buildings where the Russians took shelter, but it's unclear if the strikes were effective.

On another feed, a reconnaissance drone zooms in to observe a small group of Ukrainian civilians — mostly elderly men and women — outside an apartment building.

Around 680 civilians are understood to be inside the city, district administration head Andrii Kanashevych said on Oct. 16. With Russian soldiers now holding much of Kupiansk and cutting off the roads in and out with drones, evacuation has become impossible.

As the drone pilots of the 116th recounted, Russian soldiers have often been observed disguising themselves as locals to help advance through the city.

"They move around in civilian clothes, and we can't tell if it's a local resident or an enemy soldier;" said 26-year-old bomber drone pilot Yaroslav "Tykhyi."

"This makes things particularly tricky, because we can't target them when there is a fear that we will hurt a civilian. The good thing is that we have been working here for a while and we know where the real civilians are living, and where it's definitely enemies creeping around."

Using civilians as cover, and moving past a thin or even nonexistent Ukrainian line of infantry, once Russian infantry make it into the urban area, they can advance with much greater ease, often putting Ukrainian drone teams at risk of ending up in a direct firefight.

One FPV drone operator from another unit working in Kupiansk — who requested his identity not be disclosed due to the unsanctioned nature of his comments — told the Kyiv Independent that his team, which would ideally work from a distance of three or more kilometers to the enemy, often flew missions targeting Russian soldiers in the city less than 300 meters away.

"It's hard to say how far from the front line we work;" said Tykhyi, "The dynamic in the area is fast, and the enemy is always moving forward, closing the distance to pilots like us."

"The bastards don't tend to engage in firefights with us, they just make their way closer, infiltrate, and look for signs of movement or presence among our guys that they pass on upwards (to their drone pilots and commanders)."

Lying in wait

As the artillerymen of the 15th Brigade pause for a smoke after the fire mission, one topic is on everyone's mind: Russian drones flying farther and hitting Ukrainian targets further back than what was once thought possible.

As of 2025, almost all Ukrainian large-caliber howitzer positions — like this Giatsint — have come within range of Russian FPV drones. The further back from the front line, the lower the drone density is, but if spotted, artillery pieces are hunted relentlessly.

"Because of the distance from the front line that is now covered (by enemy drones) we are forced to pull back and pull back," the artillery commander said. "The distance increases between your fire position and your ammunition depots, it makes everything more difficult."

"We have had confirmed cases of equipment damaged at 33 kilometers from the front line. You don't need to be on the actual zero line or even close to it to come into real danger."

Over recent months, Russian drone teams have not only flown further into the Ukrainian rear, but have honed increasingly clever and deadly ways to use them much closer.

Led by Moscow's elite drone units, especially the Rubicon Center for Unmanned Technologies, over 2025 Russian forces began deploying FPV drones — usually of the fiber optic variant — in ambush positions along key Ukrainian logistics routes.

Instead of only flying out when a target is spotted, these drones — nicknamed zhdun from the Russian word "to wait" — lie in ambush.

Near the base of the 116th Brigade, welders race to equip all remaining vehicles with defensive cages and nets to reduce the chance of death from a drone ambush.

One damaged vehicle shown to the Kyiv Independent illustrates how such primitive defenses can make all the difference; instead of killing the driver and occupants with an explosion on the body of the car, the zhdun drone only caused minor damage.

At the end of summer, Bohdan "Bars," a 32-year-old drone pilot in the brigade, was assigned an entirely new role.

Instead of monitoring the grey zone and bombing oncoming Russian infantrymen, his team now patrols roads in the rear, spotting awaiting zhdun drones and clearing them with small bomb drops before giving the all clear for Ukrainian logistics runs.

"The waiting drone sits there, and either sees the car on its thermal camera, or its headlights on the day camera, if they are on," he told the Kyiv Independent.

On one rotation, Bars' team became direct witnesses of the threat they were trying to liquidate, when a zhdun drone ambushed their vehicle on their way to positions.

"We saw how it rose up and we just jumped out of the car as quickly as we could, there was no way to stop or avoid it," he recalled, adding that luckily, nobody was seriously injured and the vehicle was later retrieved.

"So yeah, we understand what the threat is very well."

Pointless death

At the command point of the Kara-Dag Brigade, movement is spotted on one of the drone feeds.

In a small clearing blanketed in autumn leaves, a camouflage-wearing figure emerges from the bushes, stopping under what appears to be an apple tree.

"He's clearly lost and hungry," said Mazhor.

It only takes a few minutes between the Russian soldier being spotted and targeted. But this time, Mazhor's team isn't calling in artillery.

Back in spring, Mazhor set up a small team working with reconnaissance and bomber drones near the front line, in a function similar to that of Tykhyi in Black Wing.

The brigade already had plenty of drone assets of its own, but Mazhor wanted more versatility in what he personally had available to carry out fire missions.

"Artillery ammunition is not cheap, and it can be a waste on two or three people," he said, "so we decided not to spend money on ammunition as much, so that we would have more of it and could use it more effectively."

"In cases like this, the reconnaissance group detects the enemy's movements, and the bombers destroy the enemy for pennies."

The decision has paid off: since forming, the group has killed over 530 Russian soldiers, with more wounded, according to the commander.

Hearing the propellers of his hunter above, the soldier runs for the bushes, where the falling autumn leaves are providing less cover with every passing week.

The Russian infantryman continues scrambling through the bushes: a fatal mistake when the pilot is scanning for any sign of movement in the scratchy camera feed.

After a patient pursuit of a few minutes, the pilot locks onto his target, the payload is dropped, and the Russian soldier's journey to Kupiansk is cut short for good.

"He had his fill of apples," Mazhor said laconically as the camera zooms out and the drone returns for a battery change. One more is added to the tally that day.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Francis Farrell, cheers for reading this article. Things are really tough on the front lines at the moment, as illusions of peace talks fade and Russian drones fly further and further past the front line. It's also getting a lot more dangerous for journalists Please consider supporting our reporting.