How Soviet nostalgia and silence enable wartime complicity on Russian YouTube

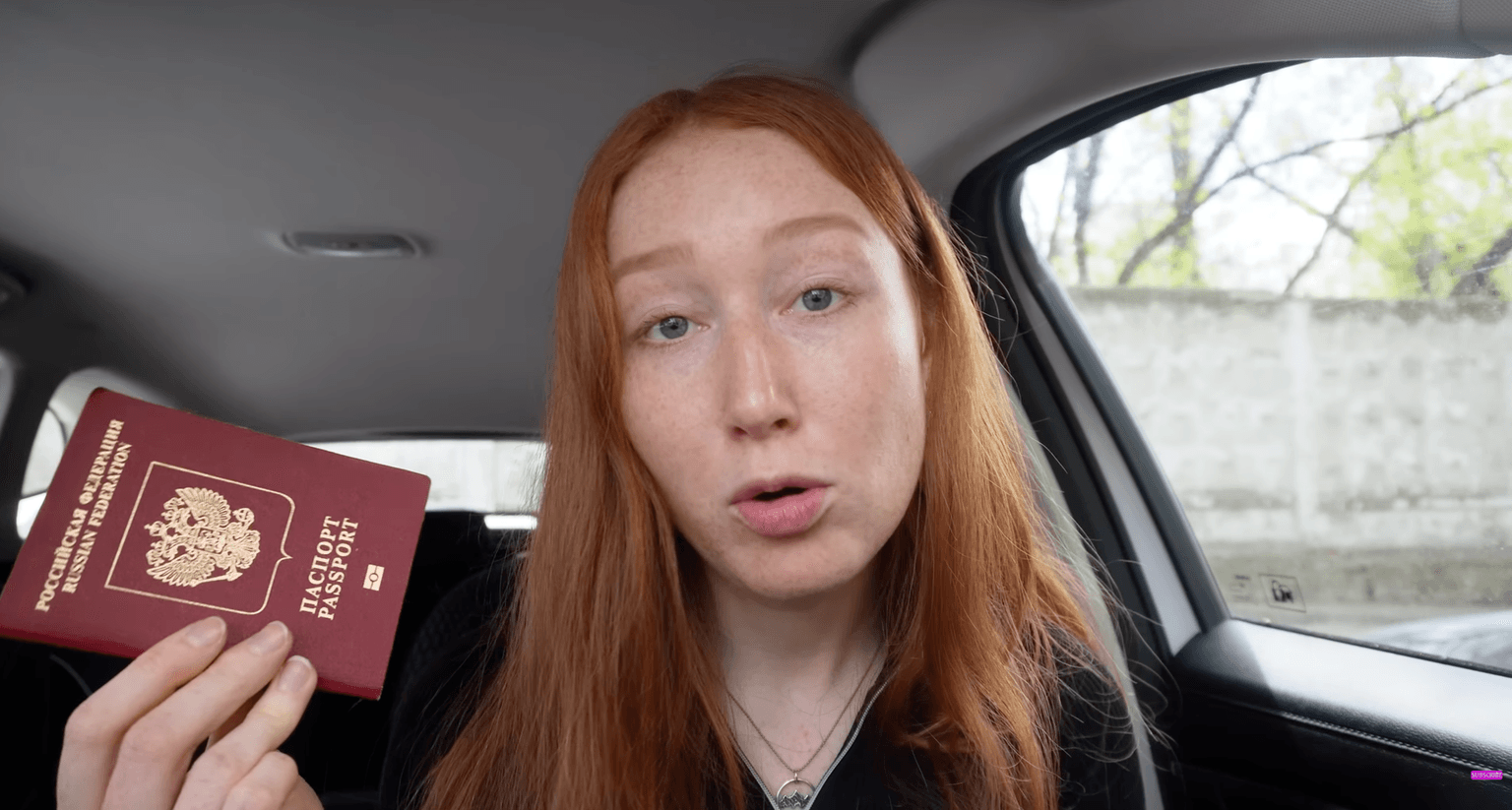

Screenshot from "Eli from Russia" YouTube channel. (YouTube)

Melanie Gottdenger

Cultural historian

"Everyone was equal," the kerchiefed babushka of Eli from Russia — a YouTuber who documents everyday life and regional culture across the Russian Federation — tells her granddaughter wistfully, recalling life in the Soviet Union.

"There were no rich and poor." And as Russian missiles strike Ukrainian cities, Eli's grandmother remembers something else with longing: "We worked for our country. And it was united."

The Russian public's complicity in the war of aggression against Ukraine is confounding and devastating to many of us in liberal democracies.

If, as Eli contends, humanity is a complex and glorious kaleidoscope of cultures with more in common than not, how does this self-proclaimed ambassador of Russian culture justify omitting responsibility, politics, and power from her commentary on life in Russia? And what are the consequences of doing so?

Since 2017, the twenty-something influencer with flowing auburn hair and an easy bohemian manner has documented her travels across all eighty-three federal subjects of Russia. Eli films in English, addressing a global audience.

Wherever she goes, she asks the same question: Was life better in the Soviet Union, or today? The answer is resounding. From Cossacks to Nenets to Tatars, from tracksuit-clad young men in Volgograd to babushkas in steppe villages, most agree that life was better in the old days.

What Eli captures, often without comment, is not simply nostalgia for youth or stability, but a specifically Soviet nostalgia — a selective memory that flattens historical violence and oppression and, in the context of Russia's war against Ukraine, dissolves responsibility.

In a recent episode, Eli travels to Belgorod, near the front lines. Between rushing into bomb shelters and remarking on how much the city has improved since last year, she interviews a young woman whose boyfriend was killed fighting in Ukraine. There is no discussion of what either woman thinks of the war, nor any frustration at the vast numbers of young Russian men mobilized or killed since the launch of the so-called "special military operation."

The episode orbits an unacknowledged black hole.

Soviet nostalgia — the child of Soviet propaganda — emerges here as a revisionist force that reshapes historical memory in dangerous ways. In Central Asian republics Eli visits, men tell her that the Soviet Union provided economic stability and reliable food. This was sometimes true.

What remains unsaid, unlearned, perhaps, is the cost of that stability: forced migrations, limited opportunity, and systematic cultural manipulation, conveniently omitted from nostalgic recollection.

In other episodes, Eli interviews Russians who insist they are disconnected from, and therefore not responsible for, their government's actions. Politics, they suggest, belongs to a distant elite, irrelevant to everyday people. For those raised in democracies where political participation can be a lifeline, this detachment is startling.

This "forgetting" reflects a subtler form of Soviet nostalgia. By the late Soviet period, many citizens had abandoned any expectation of meaningful government intervention and instead learned to endure. What lingers today is not a clear memory of repression or scarcity, but a kind of muscle memory: the normalization of political powerlessness itself.

That normalization, now expressed as nostalgia, helps sustain Russia's protracted campaign of terror and destruction against Ukraine.

When revisionist history becomes ordinary, war can proceed without public reckoning. When politics is dismissed as distant and irrelevant, responsibility disintegrates — not only for bombs falling on Ukrainian cities, but for the historical logic that makes those bombs justifiable.

Soviet nostalgia does not merely recall economic stability or social unity; it remembers a political world in which Ukraine was not fully sovereign, but absorbed into a larger imperial whole. In this revised reality, the war is experienced as an unfortunate disruption of daily life. Tragic, perhaps, but not illegitimate, nor worth risking one's own safety or comfort to oppose.

Eli from Russia insists on universal humanity: on homemade pelmeni and Soviet-born babushkas, ethnic traditions and hot tea on scenery-laden rail trips, the textures of everyday life.

This insistence is compelling and, in many ways, valid. People are people. Culture matters. But people are also citizens: beneficiaries of history and inheritors of power, whether they acknowledge it or not.

In a Russian Federation shaped by selective memory, Soviet nostalgia becomes a refuge from responsibility. For Ukraine, that refuge has devastating consequences. To tell stories without politics, in a war enabled by historical amnesia, is not to transcend conflict.

It is to carry its logic forward quietly, as bombs continue to fall.

Editor’s note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent.