Tortured Khersonians speak of Russia’s crimes

KHERSON — As Maksym Nehrov sat in the back of a vehicle, tied up, with a bag over his head, he overheard the Russians talking and he knew at once where he was headed.

They’d hunted him all over Kherson, kicking down doors and tearing through the apartments of his friends and family. He was a Ukrainian combat veteran and there was only one possible reason why they would be so thorough.

As the bag was ripped off, he found himself in a small cell, stripped of his shoes and shoelaces. He spent the night alone, awaiting what was to come.

The interrogation under torture began the following morning.

“You know what the scariest thing was?” he said, standing in the courtyard of the former Ukrainian pre-trial detention center turned Russian torture chamber, in the now-liberated Kherson, surrounded by journalists. “It was hearing the screams.”

Nehrov was just one of many civilians hauled to this center by the Russians during their eight-month-long rule of Kherson. The suffering inflicted here reached far beyond its walls.

“Yes, of course, (there were screams) very often, almost every day,” a group of four young children living near the jail told the Kyiv Independent. It was sometimes hard to sleep because of the screaming, they added.

Volodymyr Kalyuga, chief prosecutor of Kherson Oblast, said that locals were dragged here on trumped-up charges of helping the Ukrainian Armed Forces or for the crime of being related to service members, among other reasons invented by the Russians.

Authorities are currently aware of 43 victims, who stepped forward or their relatives did. “Understandably, there will be many more,” Kalyuga said.

He went on that there were four such interrogation centers in Kherson that authorities know of, and seven detention points where civilians were held. One of them was a school. Locals said that the Russians repurposed existing police buildings to hold and beat people.

Deputy Interior Minister Meri Akopyan said the Ukrainian government knows of 44 such centers across the country.

In the city of Kherson alone, over 400 crimes have been committed by Russian forces against civilians, according to President Volodymyr Zelensky. The authorities expect that number to rise.

The torture was as varied as it was inhumane. Kalyuga said that at this particular detention center, Russians beat people with wooden and rubber objects, shocked them with electricity and tied them up and put gas masks over their faces, cutting off their air supply. At least one person died under torture. Some have died from their injuries after returning home.

“When you look at the metal pipes to which prisoner’s arms were tied and gas masks put on their faces so they couldn’t breathe, then you understand that (Russians) aren’t human,” he said.

Maw of the pit

The first thing one notices when stepping into the dark chill of the recaptured jail is the scent of burning.

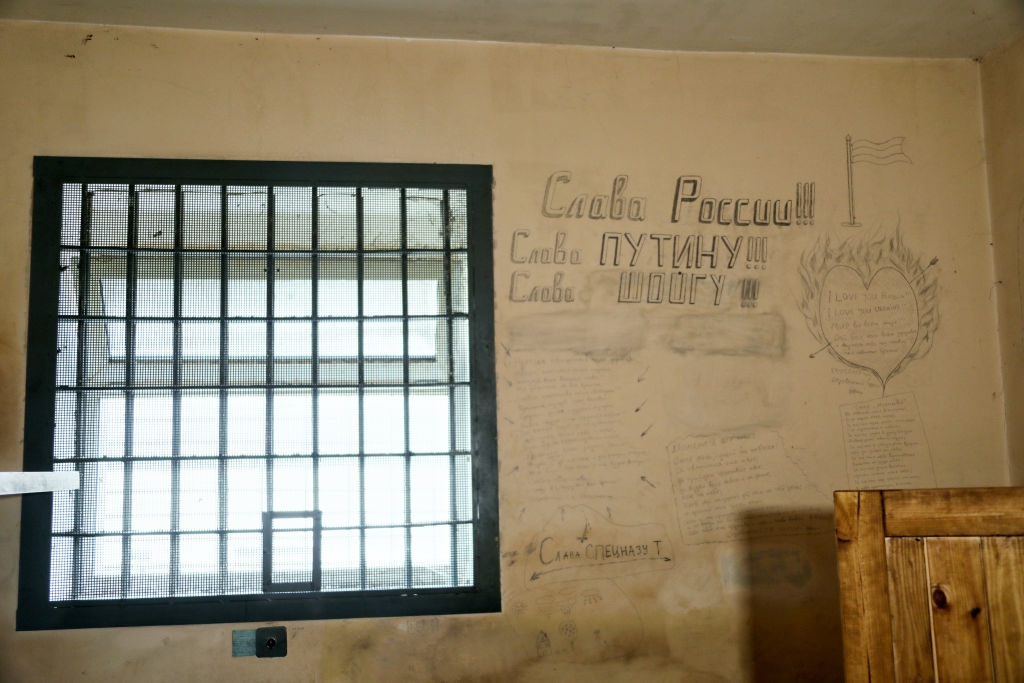

The narrow hallways are flanked by cells on both sides, which look more like rooms. The floor is littered with random papers, debris and garbage. Black graffiti saying “Russia Z” mars the walls of the garages.

Some cells are strewn with books. A few contain unused feminine hygiene pads, implying that women were held here as well.

Certain walls are covered in writings in ballpoint pen. Invocations to God and passionate rhapsodies to freedom are interspersed with dirty jokes and profane little rhymes about sex.

One cell wall has the drawing of a giant eagle soaring majestically over mountainous terrain. It’s unclear how many of these were created by alleged criminals when the place was still a Ukrainian jail and how many by civilian detainees of the Russians.

Nehrov said he drew on the walls and kept a calendar on the wall in his cell just to pass the time. During the three weeks he spent here in March and April, he had no communication with friends or family. His food consisted of small packets of buckwheat.

The captors demanded to know if he was planning attacks, working with Ukrainian intelligence or special forces.

They told him that Kyiv had fallen. “I knew that was bullshit because I heard our artillery working,” he said.

He was shocked with electricity and had other things done to him that he declined to get into, saying it wouldn’t be fair to prisoners whom the Russians took with them when they retreated from Kherson.

The people were beaten in their cells, but when it came time for interrogation, it was done in special cabinets. One of the Ukrainian troopers said that some people were tortured in the hallways. A roll of electrical wire laid on the floor in one of these corridors.

The captors also interrupted the prisoner’s sleep, barging into their cells at night and forcing them to rise, often stinking of alcohol. They forced the prisoners to stand up and yell “Glory to Russia, Victory to Russia” at the top of their lungs.

The torture got worse with time.

"At first, I have to say that in March they treated us relatively lightly… because they felt like they were the masters here,” said Nehrov.

“But when the resistance movement began acting against the occupiers, the attitude towards the captives became incredibly brutal... we heard that each day (the torture) became more and more terrible.”

When people were released, they were often driven out to the city limits and pushed out there, multiple captives told the Kyiv Independent.

Nehrov said they took him out, drove him somewhere, dumped him out with a bag on his head and told him to count to 30 before he was allowed to remove the bag and figure out where he was.

Even release was no guarantee of survival. Kalyuga said that some detainees were dumped on the edges of minefields and driven into them.

Victims of paranoia

Widespread stories of arrests and torture in Kherson don’t come as a surprise to the world anymore. When Ukraine liberated most of Kharkiv Oblast in September, basement torture chambers were discovered in multiple settlements, with 10 reportedly found in Izium alone.

Much like in Kharkiv Oblast, the primary target of Russian arrests were former Ukrainian soldiers, who fought Russia in Donbas. Among them was the father of high-school student Anna Ovcharenko, 15.

“They took my father because he fought in 2014, and released him with a sack over his head after four days,” she said. “To describe the state he was in when ... it was really bad.”

“They beat him in the kidneys, the soles of his feet were blue so he couldn't walk. Once he was there, he was beaten with sticks, with wires, with whatever they wanted.”

Ovcharenko says Russians hit in a way to not leave long-lasting wounds. She adds that Russian soldiers demanded that her father help them track down the resistance.

“They threatened that if he didn't help spy on others for them, they would take my mother and my brother as well,” she said. “He ignored them of course, locked himself at home for a few days, and it was fine.”

Some people who were arrested were actual partisans. A source in Ukrainian intelligence, who was not authorized to give his name or more information, said that some members of the underground resistance were taken.

Partisan activity was rife in Kherson and led to many deaths among the Russian forces and their collaborators, driving them increasingly paranoid.

This led to innocent civilians being attacked for absurd reasons. A Kherson resident named Denys, who declined to provide his last name, said his friend had his ribs broken and his kneecaps hit with a hammer until they were almost broken, because they found an old hazmat suit in his apartment — he used it for fishing, to wade into the water.

In fact, just being vocally patriotic was reason enough to almost get killed.

Victor Levinsky, who worked in bridge construction and the furniture business, was abducted from his home in August. The reason — his open support of Ukraine, constantly getting into arguments and saying that Russia will not last.

“A Skoda arrived with Ukrainian numbers, people in civilian clothing came out, grabbed my husband, put a bag on his head, wanted to go into the house but the dog didn’t let them,” said his wife, Natalia Levinska, a Kherson doctor. “The dog leapt forward and protected the home, it’s a huge Shepherd.”

Levinsky spent five days alternately hung by his legs, tied to a radiator and beaten purple. The heatless room and cold concrete floor gave him a nasty lung inflammation that his wife barely contained once he was out.

Levinsky says his captors were from the parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts occupied by Russia in 2014.

Defiantly, Levinsky refused to speak to them in Russian for two days before he broke down.

But one thing he would not compromise was his belief in Ukraine’s territorial integrity. He refused to say that Kherson is Russia and almost died for it.

“‘Kherson is Ukraine.’ ‘BAM.’ ‘Kherson is Ukraine.’ ‘BAM.’ That’s how they beat him,” Levinska said.

Three times, he was taken outside for a mock execution by firing squad, Levinsky said. He was put on his knees and gagged. The riflemen took aim but each time, all that emerged from the barrels was a harmless click.

He was then handed over to the Russian National Guard, which didn’t torture him but made him do menial labor, loading and unloading bricks.

The random arrest and disappearance of Ukrainians in Kherson was so frequent and so universal, that residents would recollect one case after another as if it was almost mundane, an accepted fact of life under occupation.

Railway worker Vitalii Sobko, 61, had several of his colleagues arrested. “I saw it, it was my boss that they took away, I haven’t seen him since,” he recalled. “He was a good boss, a good guy. They accused him of collaboration, but my boss was just a proud Ukrainian.”

Nasty, brutish and short

It is hard to come to immediate conclusions, but early testimonies indicate that compared to Kharkiv Oblast, Ukrainians in Kherson were generally held for a shorter time on average, but tortured just as brutally, if not more.

Two of university student Yurii Pozhydaev’s neighbors were arrested separately in May, both released after short periods of time after intense torture.

“The first one, he had been a driver for the SBU. They forced open the door and just bundled him straight into the car,” Pozhydaev said.

“To say that they beat him up is an understatement. Except for his face and a couple of fingers, there wasn't an inch of him that wasn't blue from bruises,” Pozhydaev said. “Beaten all over, ribs broken, and when he crawled home, literally crawled, I can't express how I felt, it's just so horrible, so frightening.”

The other case, that of a neighbor of Pozhydaev’s mother and also a veteran, points to the dire conditions in which Ukrainians were held, without basic human needs.

“He (the neighbor) was beaten brutally with cables,” Pozhydaev said. “When he came back, he had lost about 15 kilograms in just over a week. They didn't feed him, the clothes he was in were torn to shreds.”

The torture left some people psychologically broken. Several Kherson residents mentioned that people who came out after interrogation were no longer the same. But most of those who spoke to the Kyiv Independent said the victims managed to hold themselves together.

“I spoke to people who spent 30, 50 and more days here (in a torture chamber),” said Nehrov. “Indeed, people were psychologically suppressed but not defeated. I say this responsibly: they continued to resist.”

With Russia being driven out of the city, the healing can begin. Levinsky, who had been beaten and mock-executed by the Russians spent Nov. 14 having shots of cognac in a park square in central Kherson with his wife. They toasted to victory.

And the young children who live near the prison can finally be free of the constant blast of big guns and the screams of tortured countrymen.

“We can finally sleep in peace,” one of them said.

____________________

Note from one of the authors:

Hi, this is Igor Kossov, I hope you enjoyed reading our article.

I consider it a privilege to keep you informed about one of this century's greatest tragedies, Russia's ongoing invasion of Ukraine. With the help of my colleagues, I will continue to bring you in-depth insights into Ukraine's war effort, its international impacts, and the economic, social, and human cost of this war. But I cannot do it without your help. To support independent Ukrainian journalists, please consider becoming our patron. Thank you very much.