As Russia digs in along Donbas front line, no end in sight for civilian suffering

PERSHOTRAVNEVE, Kharkiv Oblast – Less than two kilometers from front-line positions on the border with Luhansk Oblast, silence is deceptive and never lasts long.

In one moment, the scene in any given village in this gray zone can be described as almost peaceful, as children play on sunny streets and flocks of geese mill around well-kept yards.

The intermittent artillery skirmishes waged on the fields outside the village are distant, but that can change instantly if and when Russian artillerymen choose to turn the sights on the village.

"It was lunchtime today," said a woman in her sixties, speaking to the Kyiv Independent on the street just outside her home in Pershotravneve village, Kharkiv Oblast.

"Right before lunch, they were pounding us, blasting us so, so hard; the house down the street was burning."

Before the woman was even able to give her name, the conversation was cut short by the heinous whistle of an incoming Russian artillery shell.

The shell impacted less than 100 meters away, with a couple of houses shielding the woman from shrapnel. Hands on her head and crouching down in dismay, the woman fled straight back to where she came from, the relative safety of her cellar.

With winter fast approaching, Russia is doing everything possible to stop the Ukrainian army from building further upon two devastatingly successful counteroffensives carried out in the past two months.

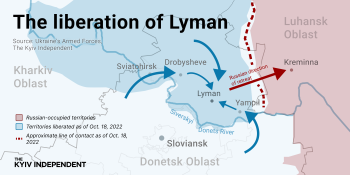

Meanwhile, Russian offensive operations in eastern Ukraine have lost steam, with evidence pointing towards a concerted effort to defend the borders of Russian-occupied Luhansk Oblast.

Moscow says it illegally annexed the region on Sept. 30.

The restoration of Ukraine's full territorial integrity hinges on the Ukrainian army's ability to successfully attack key sectors of the front line like this one. Breaking through the fortified Russian lines here serves another function – to break the illusion that the "incorporation into Russia" of Luhansk Oblast is anything more than a temporary occupation.

For residents of these front line areas like the woman in Pershotravneve, a continued Ukrainian advance will bring something much more valuable: the ability to step outside without the fear of hearing that same loud whistle of incoming fire.

Road to Svatove

Pershotravneve is the last settlement under Ukrainian control on the main road towards the key logistical hub of Svatove in Luhansk Oblast.

This area, east of the Oskil River, initially reached by Ukraine in the September counteroffensive, was liberated from Russian occupation in the early days of October.

Now, with Russia digging in along the Zherebets River running roughly along the border of Luhansk Oblast, the relief of liberation is only partial for those locals still caught in artillery range.

According to locals, 170 families lived here under occupation in the village of Cherneshchyna, seven kilometers south of Pershotravneve. Many have left in fear of retribution for collaborating with Russian forces.

During a break in artillery fire, two families with children take the opportunity to take in some afternoon sunlight.

Sisters Olena and Tetiana, who declined to give their last names out of fear of Russian troops returning, fled the brutal battles for Izium to family in Cherneshchyna, only for the latter to come under occupation a few days later.

Russian proxy soldiers went door-to-door when they first entered the village, checking for valuables and former Ukrainian service members. Residents of the tiny village kept their heads down, riding out the rest of the occupation in relative peace.

"We were working, harvesting, keeping our places tidy, just waiting for Ukraine to return," said Olena, 35. "I had a Ukrainian flag on my clothesline, the (Russian proxy) soldiers told me to take it down, but I never did it, and they just gave up."

Although the luxury of a short walk in the sun may occasionally be possible, it could be a while before proper peace returns to Cherneshchyna.

"The soldiers are telling us to hang in there, they say the Russians have really entrenched themselves in Raihorodka," said local resident Oleksiy, referring to a Luhansk Oblast village located 10 kilometers east.

"I don't know how long it will take to kick them out of there, but the most important thing is that they don't come back," he added.

Though it is unclear if Ukrainian forces can liberate Svatove and the surroundings before winter sets in, signs point to the fact that offensive operations are continuing with the aim of breaking past Russia's Luhansk Oblast line.

On Oct. 25, Ukraine's General Staff reported the withdrawal of Russian troops from four settlements east of the Zherebets RIver.

On the roadside leading into the town of Borova, 17 kilometers west of Cherneshchyna, a Ukrainian T-64 tank waits patiently for its next mission in a new coat of paint and a camouflage net.

The tank commander, a captain, identified only by his nom de guerre of "Kanzler" for security reasons, entered Borova after it was liberated by the 25th Ukrainian Airborne Brigade crossing the Oskil River.

"This is the third time that we've come in (to cities), liberated large areas, taken lots of prisoners and equipment," Kanzler told The Kyiv Independent. "Every time we feel like the war is over like we've won, but a new, even bigger task faces you right away."

"Everyone is watching Svatove now, but I think something will break somewhere else," he said. "(Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief Valerii) Zaluzhnyi isn't an idiot."

Holding the line

Further south in Donetsk Oblast, the front line has been deadlocked for four months, but even here, Ukrainian forces are looking to make a breakthrough before winter.

Situated just 25 kilometers from occupied Lysychansk, the town of Siversk has suffered greatly from some of the war's heaviest fighting. The town was on the brink of falling to advancing Russian forces in late June. Now eyes are once more on the area as a potential direction for a new Ukrainian counteroffensive.

Military activity in the area is lively – along with the regular beat of artillery fire, Ukrainian helicopters and fighter jets can be seen making regular low-flying sorties across the front line.

On the evening of Sept. 10, when Ukrainian forces liberated Izium and Kupiansk in Kharkiv Oblast, Luhansk Oblast Serhiy Haidai shared reports that Ukrainian soldiers were seen on the outskirts of Lysychansk. A month later, when nearby Lyman was liberated, a further advance encircling Lysychansk from the north was similarly anticipated.

In both cases, what seemed too good to be true turned out to be just that. Stories of recent battles from Ukrainian service members fighting in the area serve as a sober antidote to waves of optimism about collapsing Russian defenses.

Under the partial cover of a shady walnut tree at an undisclosed location outside Siversk, the Kyiv Independent spoke to the crew of a Czech-origin T-72 tank about the ebb and flow of fighting in the area.

"One day you are assaulting their positions, and the next, like three days ago, you have waves of mobilized troops with no training charging yours," said Oleh, a 39-year-old tank driver originally from a village near occupied Alchevsk in Luhansk Oblast, unable like many Ukrainian soldiers to give his full identity for security reasons.

"They are trying to take a position here, a position there, people are telling us that they are gathering a bunch of armor, hiding it somewhere near us," he said. "They still have at least twenty tanks in the area. Our first battalion tried to advance a few weeks back and got smashed up really badly."

"But Nomad tells us that they were moved to Kherson," he added. "Who the hell knows."

"Nomad," the 31-year-old commander of another T-72 parked nearby, did not rule out the possibility of an advance on Lysychansk in the near future. "Who knows, it's a really big city," he said.

"If we take the oil refinery between Siversk and Lysychansk), then we can push further. We are fixing them here, but we need to advance on the flanks for it to be possible. Just like they did in Mariupol, to give them no option but to surrender their positions."

As the regular Russian army continues to be bled of equipment and experienced personnel, much of the responsibility for defending occupied Donbas is being picked up by the Wagner Group, the shady Kremlin-backed private military company led by Vladimir Putin's close ally Evgenii Prigozhin. On Oct. 19, the building of the "Wagner Line," a length of trenches stretching from the area around Lysychansk south beyond the front line city of Bakhmut and fortified with pillboxes and anti-tank "dragon's teeth," was reported.

Attacking fortified positions is challenging anywhere, but as with similarly-named fortified lines in World War II, the ability of the "Wagner Line" to succeed in halting an anticipated Ukrainian advance remains in doubt.

Ukrainian tank driver Oleh spoke excitedly of his tank company's recent engagements with Wagner forces.

"These Wagnerites were just sitting in their positions, and we come in on two of our tanks and just start lighting them up!" he said. "I look at what is left of them, and I just imagine what kind of hell it is at the other end."

Survival mode

Between the booms of outgoing artillery, the town of Soledar in Donetsk Oblast is eerily quiet. Located just north of Bakhmut, the eastern outskirts of the town have been heavily contested since May, with Wagner troops briefly entering a factory within the city limits in August.

"You can't even call what is happening here fighting," said Maksym, a local man who, like almost all residents of these areas, declined to give his last name out of fear. "It's just systematic extermination."

One night in early October, Maksym's apartment building was hit by a tank round, which he claims, according to its trajectory, could only have been fired by the Ukrainian side.

With little access to information about the progress of the war and unending scenes of haphazard destruction around them, many locals are holding out for a quick end to hostilities. Barely any conversation ends without the phrase "It doesn't matter to me who's in power, the only important thing is peace" emerges with little variation in wording.

In this psychological state, people's hopes are often contradictory to the political realities of Russia's war.

"We are free Ukraine, we are on our own land, and we won't be dependent on anyone," said Olha, a 73-year-old resident of Siversk. "But they just need to sit down at the negotiating table and stop the shooting right now."

Winter is fast approaching, and for residents of front-line towns like Siversk and Soledar, living conditions will only continue to deteriorate.

Battered relentlessly by six months of shelling, homes, and apartments have been abandoned for basements, the firm walls of which provide refuge both from the fighting and the creeping cold. In the absence of gas and electricity, residents have turned to makeshift wood-burning stoves with chimneys curling out of the basement windows on street level.

"The things we need most are electricity... and peace," said Olha. "Did I really live seventy-three years just to die in my basement?"

Despite the mass exodus to the basements, civilians are still killed on a regular basis.

"Two died here last Saturday," said Olha. "A doctor and a priest: He came here to repair his church and was killed the next day."

With long journeys outside too dangerous to justify, many are buried in makeshift graves right outside their front door.

Teams of volunteers visit Siversk and Soledar regularly, aiming to evacuate locals to safer areas far beyond the front line. Despite the dire conditions, many still refuse their offers.

"The older people won't leave. One can't move at all, another doesn't want to abandon their flat, and yet another one wants to be buried next to her husband," said Olha. "I understand many people will die here in their homes, but their minds are made up."

Found frying up potatoes outside a five-story apartment building in Siversk shredded by multiple rocket strikes, Volodymyr Reznikov, 64, assumed a stoic outlook on the upcoming ordeal.

"They are cutting the electricity off in all the cities now," he said. "We have gotten used to living like this. Do you think they'll be cooking potatoes on the street like this in Kyiv? They will break first, and we will survive."

Note from the author:

Hi, I'm Francis Farrell, who wrote this piece from on the ground in some of the areas hardest hit by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. As you read this, Russia is trying to plunge Ukrainian cities into a deep, cold winter, while Ukrainians in Donbas are left in an even more dire position without basic utilities. The Ukrainian army will nonetheless continue working to liberate the occupied territories, but there is still a long way to go before victory. Please consider continuing to support our reporting.