More than Tomahawks: What Ukraine’s soldiers say they actually need

A Ukrainian soldier of the 65th Mechanized Brigade drives a car on a road near the frontline village of Robotyne, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Ukraine, on Oct. 1, 2023, amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine. (Roman Pilipey / AFP via Getty Images)

Ihor, a company commander, was driving alone out of Pokrovsk, already semi-encircled by Russian forces, in September when the first Russian first-person-view (FPV) drone hit the back of his car, tearing the roof.

The second flew in immediately after, hitting the rear tire. He drove five kilometers before the third FPV struck the engine bay of his car. It stopped moving.

“The first drone intercepts a car, and then one or two FPV drones fly in,” Ihor from the 36th Marine Brigade deployed in eastern Donetsk Oblast said, describing Russia’s killer drone tactic against cars.

While the Ukrainian military also lacks prestigious Western-supplied weapons and equipment, soldiers and commanders say the shortage of basic resources — from cars to drones and people — makes it extremely difficult to hold back the relentless Russian offensives. Though Ukraine has been eyeing the U.S. to finally green-light the supply of long-range Tomahawk missiles, those on the ground say the lack of more basic needs is a more pressing issue, and often shortages of critical but more rudimentary equipment play just as decisive a role.

Forced to get out of his car, Ihor walked three to four kilometers on foot before fellow soldiers picked him up.

“They hit all cars,” Ihor told the Kyiv Independent.

“They just see someone driving by, and they'll hit absolutely every car.”

Ihor, like other commanders and soldiers who spoke to the Kyiv Independent for this piece, asked to be identified by first name only so he could speak freely without his command’s authorization.

Cars

Ihor says his infantry company currently only has two working cars, after three others were made inoperable either by Russian drone attacks or the often treacherous roads of eastern Ukraine. A typical infantry company at this stage in the war has around 50-70 men.

His unit has no armored vehicles because they are Russia’s priority targets and typically get destroyed quickly. But even armored equipment such as US-made MaxxPro mine-resistant vehicles or Turkish-made Kirpi is louder and harder to accelerate than normal cars, making it more challenging to avoid and escape Russian FPV drones, according to Ihor.

With Russia constantly stepping up its drone game and coming up with FPVs that now have a range of about 20 kilometers, the gray zone extends as far as five kilometers from the front — significantly crippling Ukrainian logistics.

His unit relies on cars to bring guys to the front, with its speed and mobility allowing them to drive as close as 500 meters to a kilometer from the positions. But the cars quickly get destroyed or ruined by the beat-up roads in the Donbas, and the guys have to chip in from their own pockets for the repair, since fundraisers take too much time. Charity foundations said they are receiving fewer donations from the public the longer the war rages on.

Ideally, the unit would have five working cars so when one gets destroyed, another can easily come and help out without the risk of losing all cars, Ihor said.

“A car has a life for up to a month,” Ihor said. “A week or two, and the car is gone.”

Other commanders and soldiers deployed across the front line have also told the Kyiv Independent that the car deficit is significantly disrupting their fighting ability.

Anton, a commander of a tank company in the 59th Assault Brigade, admitted that “there are almost no cars” to bring his crews to the position, even though they have enough tanks and shells.

A soldier from the 63rd Mechanized Brigade named Dmytro said that there is constantly a car deficit because they often get destroyed, damaged, or break down.

An infantry company often just have one car to be used for getting people to the front, delivering food and weapon supplies even though they usually need to happen simultaneously, according to Vladyslav Urubkov, a director of the military department at the Come Back Alive charity foundation.

“These things often need to happen at the same time, but if the vehicle has already gone to the front line to transport personnel, it can’t also deliver food — and vice versa,” Urubkov told the Kyiv Independent.

“The army is always working under shortages, but when it comes to vehicles, it’s truly a matter of life and death.”

The vehicles that are most in demand have been pickup trucks and minibuses since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, according to Andrii But, Head of the HeroCar project run by the Ruslan Shostak chairty foundation, which supplies cars to the Armed Forces.

But said that the organization is also seeing a growing demand for motorcycles, particularly cross-country ones, from front-line units.

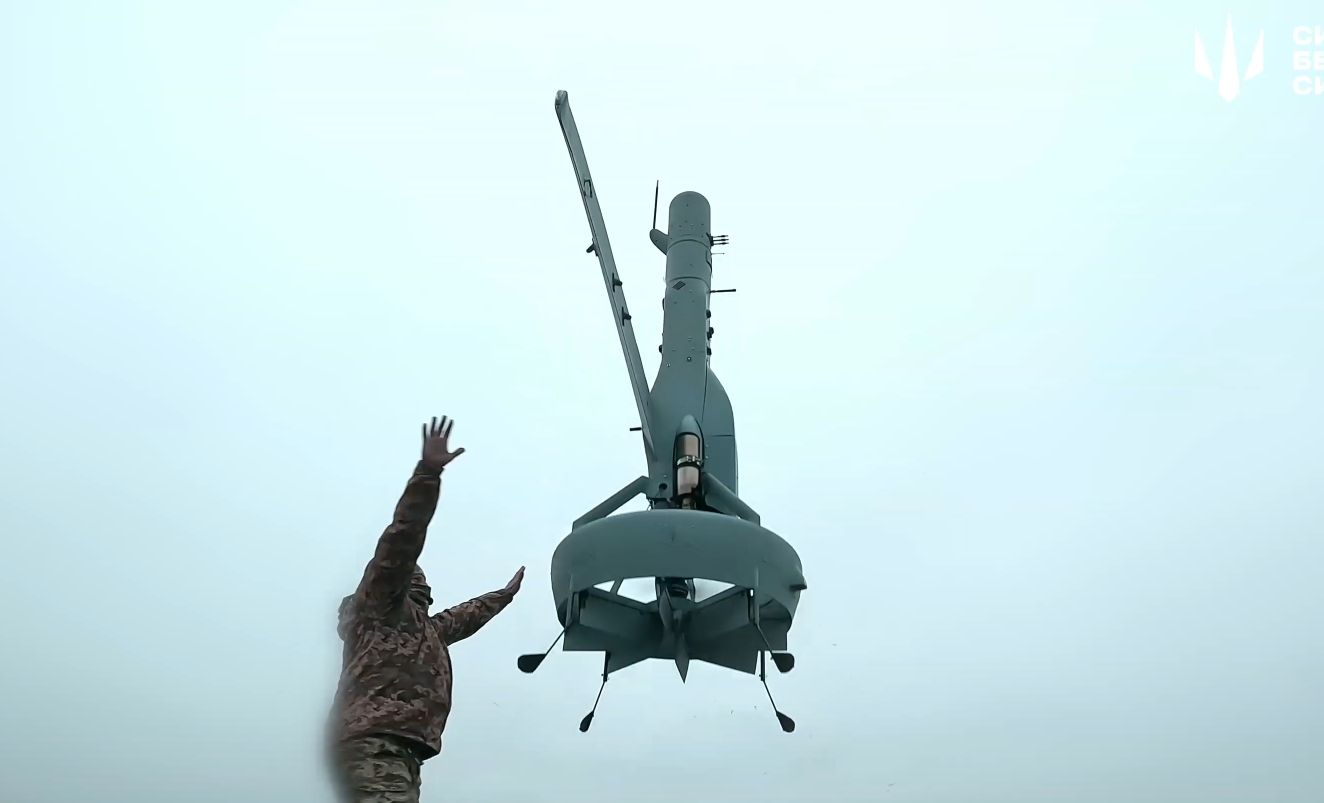

Drones

With drones getting lost constantly, either because they are downed by Russian troops or due to electronic warfare, Ukrainian troops are often short on drones, and launch fundraisers to help cover the cost of replacing them.

Illia, a commander of an anti-drone platoon in the 80th Airborne Brigade deployed in Sumy Oblast, stressed that there is a lack of “everything,” from drones to manpower.

“The situation with supplies (from the military command) is terrible at the moment,” Illia told the Kyiv Independent, suggesting that the state is “not interested” in diminishing the stark deficit.

"And you have to buy everything yourselves.”

Illia says that his unit lacks the necessary reconnaissance drones to see beyond the line of sight, preventing them to “see anything beyond five kilometers” and unable to disrupt Russian logistics. He said his unit needs 10 times more drones than are supplied.

Resources are not equally dispersed across Ukrainian units, allowing some to have more than others. A few drone pilots from other units, such as from the Unmmaned System Forces of Ukraine and the 82nd Airborne Brigade, said that they have enough drones.

The Ukrainian military uses about 9,000 drones a day, inflicting about 85 percent of the damages on Russia's equipment and troops compared to 67 percent, according to Dmytro Zhmaylo, co-founder and executive director of the Ukrainian Security and Cooperation Center, a Kyiv-based think tank.

With Ukrainian infantry units often "depleted" of manpower, especially of young men, drones are particularly important in an army where an average soldier's age is around 40 years old, Zhmaylo said.

People

Ukrainian military experts who spoke to the Kyiv Independent stressed that the Ukrainian military’s number one shortage is manpower. Zhmaylo stressed that sometimes certain Ukrainain units may have drones in bulk, but no pilots to fly them.

Serhiy Hrabskyi, a retired Ukrainian colonel and military analyst, said that well-trained reserves are what the military lacks the most.

The Ukrainian military has always grappled with a worsening manpower shortage since fewer people began to voluntarily join the army in 2023, after the initial influx of volunteers all headed to the war.

While the mobilization still continues, many units — particularly in the infantry — are critically lacking men in battle-hardened brigades that have had to face heavy losses after fighting extensively in hot spots of the war. The soldiers are often sent to the positions for weeks, and months in some cases, due to the lack of new trained recruits and the challenges with infils and exfils in the drone era.

The Russian military on the other hand is accumulating troops each month, recruiting more men than the losses they face on the front, Commander-in-Chief of Ukraine’s Armed Forces, Oleksandr Syrskyi, admitted in August.

Despite the critical need for mobilization, Ukrainian politicians, including President Volodymyr Zelensky, rarely mention the topic, with political experts saying that they are likely afraid of their rating falling by tackling a highly unpopular topic. It remains a taboo topic in politics.

Ukraine is mobilizing about 30,000 people per month, but only a third of them are fit to fight, a senior Ukrainian official told the Kyiv Independent in July on condition of anonymity.

Of the roughly 30,000 that Kyiv says it is mobilizing, about half of them are the soldiers who are returning from AWOL, or absent without leave, according to another Ukrainian official familiar with the matter.

Bohdan Danyliv, head of military affairs at Serhiy Prytula charity foundation, said that “there is absolutely not enough people,” especially with the battle-hardened brigades barely or not receiving new, well-prepared recruits at all.

Danyliv pointed out that the Ukrainian command still frequently sends recruits into newly formed units that lack battlefield experience or in headquarters rather than filling up the gaps in battle-hardened brigades. Training centers also often lack the resources to adequately train new soldiers, which, for instance, forces them to use fake grenades or rocks instead of the actual ones to practice throwing, he added.

Danyliv stressed that this is especially an issue as “kill zones” of drones continue to expand for both sides, making it extremely dangerous to go anywhere near the front.

“I would even say that it is no longer a matter of material needs,” Danyliv told the Kyiv Independent.

“There are not enough people, there is not enough proper coordination, there is not enough communication between units (and between different ranks).”