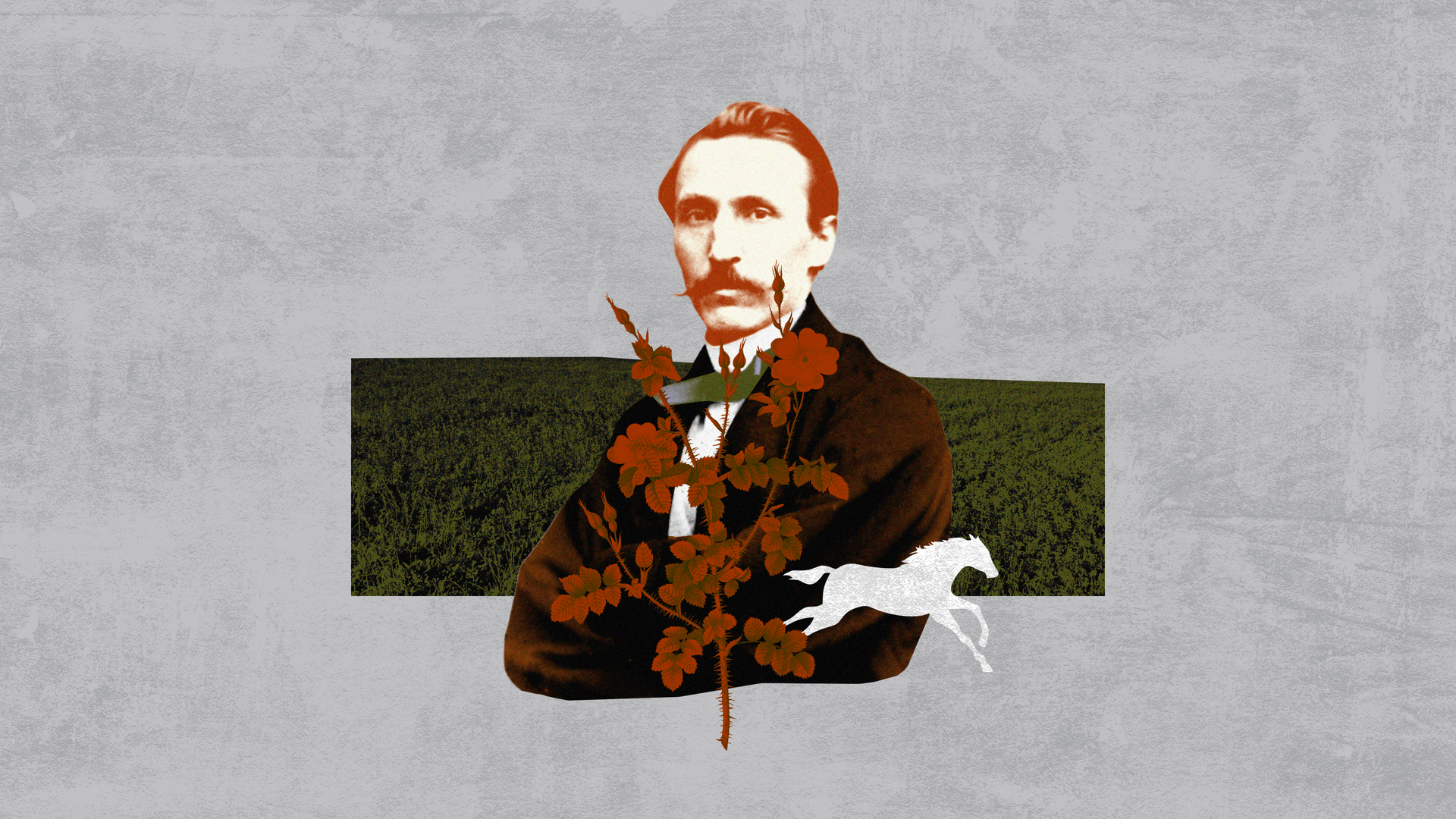

Olha Kobylianska, a Ukrainian modernist writer and feminist. (Anastasiia Starko / The Kyiv Independent)

In Olha Kobylianska’s 1891 novella “A Human Being,” the heroine Olena commits an unforgivable transgression. Not adultery, not theft, not the abandonment of her family — her "crime" is intellectual freedom. She is a woman who thinks for herself and, far worse in the eyes of society, speaks her thoughts aloud.

"Heaven knows from where she ferreted out those crazed notions and dragged them into the light of day — and then swallowed them whole, in the fullest sense of the word! And how she knew how to talk about them afterward!" Kobylianska writes, voicing the inner turmoil of Olena's mother.

"Men — young men at that — would crowd around her, and she would speak, analyze, argue — God have mercy! Conversations scorching like hot iron; dangerous words such as socialism, naturalism, Darwinism, the woman question, the workers' question buzzed like bees around the respectable ears of (Olena's mother) and frightened her like specters in broad daylight, terrifying her devout soul, unnerving her and bringing on sleepless nights…"

Born in 1863 to a minor civil servant's family, Kobylianska spent most of her life in Chernivtsi, located in modern-day western Ukraine. The city was simultaneously a provincial backwater of the Habsburg Empire and a cosmopolitan crossroads — a place where Ukrainians, Austrians, Poles, Romanians, Jews, and countless others interacted daily across different identities and languages.

"Growing up among Ukrainians, Germans, Poles, Romanians, Jews, and others in the Habsburg borderland, she experienced pluralism as a daily reality. This environment…encouraged her to think across cultures rather than within a single national or ideological frame," Professor Yuliya Ladygina, a specialist in Kobylianska's life and work, told the Kyiv Independent.

"Bukovyna's relatively liberal political climate further inclined Kobylianska toward individual autonomy, cultural self-fashioning, and ethical responsibility over rigid collectivist doctrines. Her writing thus blends Western European philosophical currents — German Romanticism, (the philosopher Friedrich) Nietzsche, and feminism — with a conscious commitment to Ukrainian culture, producing a worldview that resists both narrow nationalism and uncritical cosmopolitanism."

Kobylianska's upbringing, coupled with her engagement with late-19th-century intellectual debates, gives added philosophical depth to her treatment of the "new woman," offering a nuanced perspective that anticipates and, in some respects, surpasses the feminist explorations of later writers like Virginia Woolf.

"Kobylianska insisted that liberation begins with intellectual agency, ethical responsibility, and the capacity to think independently."

Social convention, family obligation, and patriarchal authority repeatedly conspire to narrow the space in which Kobylianska’s heroines exist, sometimes even forcing them into compromise or outright defeat. Yet Kobylianska does her best to avoid consigning them to martyrdom. Her heroines do not throw themselves under trains like Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina or walk into the sea like Kate Chopin's Edna Pontellier. Instead, they face a more excruciating question: How does a woman preserve an authentic version of herself when nearly every avenue of self-expression is denied to her?

Within Ukrainian literature, Kobylianska occupied a distinctive position. While contemporaries such as Ivan Franko were central figures in the development of literary realism, focusing on social conditions and public life, and her close friend Lesia Ukrainka worked mainly in poetry and drama — often drawing on historical, mythological, or symbolic material — Kobylianska concentrated primarily on psychological prose, especially the inner lives of her characters.

Kobylianska’s novel "The Princess" (1911) was written after "A Human Being" and presents an even more complex and somber psychological portrait. In "A Human Being," the protagonist Olena articulates a central demand for personal autonomy, rejecting the idea that a woman should be treated as property within marriage or family arrangements. "The Princess" follows Natalka, who grows up in a family that identifies with a declining aristocratic tradition while experiencing economic hardship and social insecurity.

Natalka’s mother is primarily concerned with improving the family's social standing through marriage, and Natalka is treated as a means to that end. As a result, Natalka grows up in an environment where emotional relationships are closely tied to social ambition, and expressions of affection and virtue are shaped by considerations of status and advantage rather than personal attachment. As a result, she develops a rich inner life that she is determined to preserve at all costs.

"Her eyes kept returning to the revolver. After a long struggle, she came to one thought again: that to leave now, in time, would be the most dignified, the most satisfying. But she feared one thing — being forgotten. 'Oh, only do not let me be forgotten!' Natalka thought. She dreamed of dying among flowers, with bees humming, with the sun rising afterward in all its splendor. And indeed the sun rose — majestic, prophetic — kissing her with all its golden brilliance. But she was not dead," Kobylianska writes, describing Natalka's inner turmoil when her literary manuscript, the confirmation of her intellectual freedom, is rejected by publishers.

In "A Human Being," Olena enters a marriage she does not desire to relieve her family’s financial difficulties, a decision that limits her ability to act as an independent individual. By contrast, in "The Princess," Natalka resists defining herself according to the expectations of her family and social environment. As a result, she becomes increasingly isolated. The novel presents this isolation as a consequence of her commitment to her own sense of identity, rather than solely as a product of external circumstances.

Kobylianska's engagement with the intellectual currents of both Ukrainian and broader European culture establishes her as a pivotal figure in literary history. However, despite her significance, relatively little of her work has been translated into English. Issues of language and literary access were also present during her lifetime, too.

What makes Kobylianska's literary achievements even more remarkable is that she did all of this writing in Ukrainian, rather than the German language in which she was educated. Although she was deeply inspired by the great German thinkers of her time, German and Austrian editors made it clear that the themes of her work — women’s inner lives, social constraints, and peripheral provincial settings — were of "little interest" to a wider European readership.

"Choosing Ukrainian, therefore, meant turning away from the prestige, institutional support, and broader readership associated with imperial culture in favor of a language widely regarded as provincial and culturally secondary. In this sense, writing in Ukrainian functioned as an act of cultural commitment and intervention within an emerging national project," Ladygina explained.

"Writing in Ukrainian was thus less a rejection of the empire than a strategic decision to modernize Ukrainian literature from within by importing European ideas and aesthetic models. Its political weight lies not in linguistic purity or nationalist exclusivity, but in her effort to expand the cultural and intellectual horizons of Ukrainian writing itself."

During the 20th century, the public reception of Kobylianska's work changed in ways that reflected shifts in Ukraine’s political and cultural history. In the early Soviet period, she was presented by the Communist authorities as a progressive writer, but later her emphasis on individual experience and psychological analysis was less compatible with the principles of Socialist Realism.

As a result, her work was published selectively, and some of her more formally and thematically complex texts were not widely circulated. After Ukraine's independence in 1991, scholars undertook broader reassessments of her writing, and she came to earn her rightful place as a key figure in the development of Ukrainian modernist literature.

Today, as Ukraine fights to preserve its sovereignty and cultural identity, Kobylianska's work resonates with even greater force. Her insistence on women's intellectual autonomy, her refusal of imperial cultural hierarchies, and her commitment to developing Ukrainian literature on its own terms rather than as a provincial echo of Russian or German models all speak directly to contemporary Ukrainian struggles for self-determination.

"Her understanding of freedom as inner self-determination rather than a purely external or collective condition speaks directly to Ukraine’s current reality," Ladygina said.

"Kobylianska insisted that liberation begins with intellectual agency, ethical responsibility, and the capacity to think independently. Kobylianska's ideas frame resistance as not only military or territorial, but ethical and intellectual—reminding us that Ukraine's survival depends as much on cultivated individuals and engaged thinkers as on force of arms."

Note from the author:

Definitive, widely available English translations of much of Kobylianska’s work still do not exist outside of academic journals and anthologies. Her writing deserves to be read more broadly.

Yulia Ladygina’s translation of “The Princess” is forthcoming from Harvard’s Ukrainian Research Institute in 2027.

Kobylianska’s “On Sunday Morning She Gathered Herbs,” in Mary Skrypnyk’s English translation, was published by Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press in 2001.