Invasion rooted in history: A review of Serhii Plokhy’s ‘The Russo-Ukrainian War’

For many people worldwide, Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine appeared unprecedented and unthinkable. However, for those familiar with Ukrainian history, it unfortunately represented a familiar pattern. In his latest book, "The Russo-Ukrainian War: A Return to History," the historian Serhii Plokhy explores how the myths deeply intertwined with Russian statehood can be attributed to Russia’s fixation on Ukraine's destruction over the centuries.

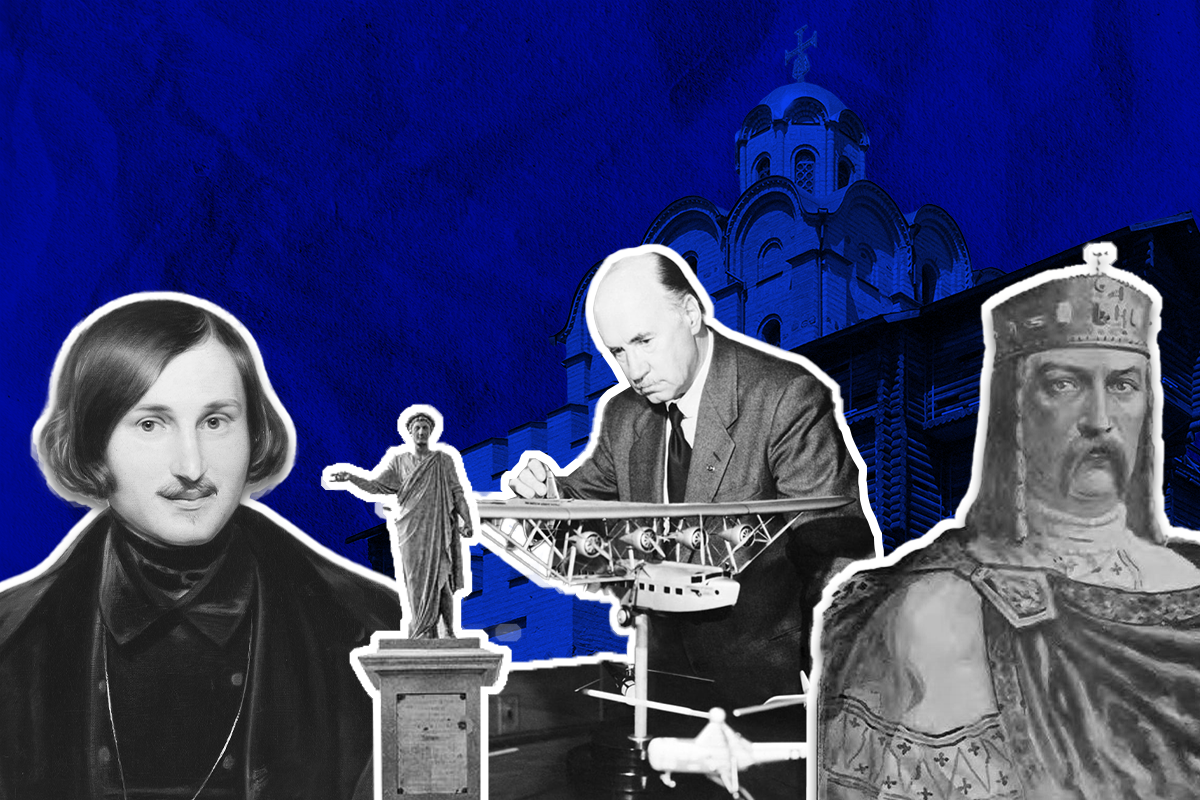

A professor at Harvard University, Ukrainian-American historian Serhii Plokhy has authored several books on Ukraine, positioning him as the preeminent scholar in his field today. Among his most notable works are "The Gates of Europe," a comprehensive history of Ukraine; "Chernobyl: The History of a Nuclear Catastrophe"; and "The Man with the Poison Gun," which goes into the assassination of the radical OUN-B leader Stepan Bandera.

As Plokhy explains in his latest book, much of Russia’s myth-making in regard to its aggression against Ukraine is tied to its claim as the "true" successor state of Kyivan Rus, a developed medieval state that included most of modern-day Ukraine, Belarus, and western parts of Russia. This belief "had already embedded itself in the consciousness of the Russian elites by the late 15th century" and originates back to the rule of the Grand Prince of Moscow Ivan III, which lasted from 1462 to 1505.

Ivan was "of the many descendants of the Kyivan princes" and was embroiled in a war to take over the independent Novgorod Republic. "It was in the midst of Ivan’s war against Novgorod, one of the heirs of Kyivan Rus, that the myth of Russia’s Kyivan origins was born, originally as a dynastic claim. Ivan declared himself the heir of the Kyivan princes, claiming the right to rule Novgorod on that basis," Plokhy writes. Novgorod was eventually absorbed into Moscow’s realm in 1478, and "the birth of the independent Russian state resulted from the victory of authoritarianism over democracy."

By contrast, the trajectory of the modern Ukrainian state can be traced back to the Cossacks, "freemen and runaway serfs" who established a powerful and semi-autonomous military state in the mid-17th century in the Zaporizhian Sich. The eventual destruction of the Cossack Hetmanate during the rule of Empress Catherine II (1762-1796), resulting in its territorial integration into the Russian Empire, would subsequently serve as a rallying point for Ukrainian nationalist movements throughout the 19th century and beyond.

As Plokhy explains, "that memory would become a powerful instrument in the hands of those who created the modern Ukrainian nation. They would produce a new Ukrainian anthem beginning with the words 'Ukraine has not yet perished.' The reference was to the continuing existence of the nation in spite of the destruction of its spiritual temple, the Cossack state."

Over the years, Ukraine's history has been punctuated by Russia – whether it be the Russian Empire, the USSR, or the Russian Federation – consistently attempting to destroy Ukrainian national identity. During the USSR, Plokhy explains, the Bolsheviks first tried to unite the former lands of the Russian Empire through "cultural concessions to the nationalities, recruitments of supporters among their intelligentsias, and recognition of their right of political autonomy and use of their national languages in the conduct of public affairs."

However, these "concessions" were short-lived. Joseph Stalin's ascent to power in 1924 came with Russification policies that were implemented through brutal repressions. This included the Holodomor (1932-1933) an artificial famine that killed an estimated four million Ukrainians. "In the month leading up to the start of the famine, Stalin warned his associates that such measures were needed to prevent loss of control over Ukraine," Plokhy writes.

According to Plokhy, Ukrainians constituted the largest group of political prisoners within the USSR. The cycles of "coexistence" between Russia and Ukraine, followed by repressive periods, continued until the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991. Ukrainians were sent to penal colonies as late as the 1980s and by the time Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985, "Soviet officialdom’s dream of turning Russians and Ukrainians into one people, in linguistic and cultural terms at least, seemed closer to realization than ever."

Exploring these periods of oppression is important, as they highlight the fallacy of the Russian propaganda claim that Ukrainians and Russians are "brotherly nations." It also highlights how badly Russian dictator Vladimir Putin and the Russian military leadership underestimated the strength of Ukrainian statehood in the lead-up to the full-scale invasion, believing that they would be met as liberators.

Plokhy also addresses the West’s shortcomings in safeguarding the security of Ukraine and neighboring countries post-independence. For instance, he goes into how Ukraine was pressured by the U.S. into signing the Budapest Memorandum in 1994, which led to the surrender of its nuclear arsenal for subpar security guarantees.

The problem with the Budapest Memorandum was "the absence of commitments to protect Ukraine in case the promises were broken and Ukraine was attacked" whereas Ukraine was looking for "iron-clad guarantees." According to Plokhy, the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022 "exposed the ineffectiveness of the assurances offered by the Budapest Memorandum and accompanying treaties."

France and Germany's choice in 2008 to reject a NATO membership plan for Ukraine and Georgia was also a major misstep, according to Plokhy. The persistent attempts by European leaders to engage in trade and diplomacy with Russia, despite the invasions of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014, highlighted their limited grasp of the adversary they were dealing with.

"The Russo-Ukrainian War" was published more than a year after the onset of the full-scale invasion, and military analysts speculate that the war will extend well into 2024 at minimum. It is commendable that Plokhy sources from on-the-ground observers, including the Kyiv Independent (as listed in his bibliography), to maintain a sense of vitality when writing about current events. However, there lies ample content to be explored in the coming years regarding the ongoing battles along the eastern and southern front lines, as well as the multitude of Russian war crimes committed against Ukrainian civilians and soldiers on a daily basis.

In that sense, the book might have been better suited to focus on the build-up to the full-scale invasion. The in-depth focus of "The Russo-Ukrainian War" on the past is what distinguishes this book from other recently-published books about Ukraine. It also makes the book an invaluable resource countering Russian propaganda, which erroneously asserts that the war could have been averted were it not for the U.S. and NATO expansion.

With his deep knowledge of history, Plokhy also permits himself to look into the future, writing that Ukraine’s ability to defy Russia’s expectation of falling in a matter of days and galvanizing world support "ensured (Ukraine’s) continuing existence as an independent state and nation" and that the country will "emerge from this war more united and certain of its identity than at any other point in its modern history."

Interestingly, he also writes that Ukraine’s victory "is destined to promote Russia’s own nation-building project." According to Plokhy, Russia will have no choice but to part ways with its imperialistic past. After all, such a path has been followed by past empires following military defeat. The acclaimed Russian writer Sergei Lebedev – whose body of work also draws from history – said something similar in a feature for the Financial Times back in the spring, namely that "if Russia is to have any future, it will have to become another country."

In this sense, the subtitle of "The Russo-Ukrainian War" – "A Return to History" – is particularly on point. Plokhy’s latest book stands as a testament to the necessity of historical insight in shaping our understanding of wars and, more importantly, their far-reaching consequences in the years that follow.

"The Russo-Ukrainian War" is out now and can be purchased from most major book retailers.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, thanks for reading this book review. There is an ever-increasing amount of books about Ukraine available to English-language readers, and I hope my recommendations prove useful when it comes to your next trip to the bookstore. Ukrainian culture has taken on an even more important meaning during wartime, so if you like reading about this sort of thing, please consider supporting The Kyiv Independent.