KRYVYI RIH, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast – The country’s industrial heavyweight, Kryvyi Rih is known globally for its metallurgy and iron exports.

But it's not only the metal industry that keeps the city of 600,000 people running. Machine-building, construction, chemical, woodworking, and textile industries provide thousands of jobs for locals.

When Russia’s full-scale war broke out on Feb. 24, most of the city’s production stalled, leaving many families with little means for survival.

Supply chains in the city are linked to one another so when one area of production gets put on hold it disrupts the whole system.

As the front line gradually moves further away from the city as the Ukrainian military moves to launch a counter-offensive in Kherson Oblast, factories in Kryvyi Rih have started to resume their work in a bid to revive the economy.

The war, however, brought changes to their day-to-day routine. Enterprises had to get used to working under air raid sirens and adjust production to meet new wartime demands, making goods for the city's defense.

Helping the army

In the first days of Russia’s full-scale invasion, employees of ArcelorMittal Kryvyi Rih – Ukraine’s largest steel plant that has been in private hands since 2005 – felt they had something to offer to the military.

They started producing anti-tank hedgehogs, anti-car spikes, cast-iron stoves, and body armor. Metallurgists, however, made the products out of scrap metal and remnants of high-alloy steel, instead of out of steel the plant itself produces.

“At the very beginning it was hard to find suitable materials,” said Mykola Yefimenko, head of the repair service in the steel casting department.

“Take anti-tank hedgehogs, for instance, we were making them out of leftovers of some used rail that we had at the factory,” he went on.

“For (bulletproof) plates, we used high-alloy steels. There were also attempts to use leaf springs,” Yefimenko said, adding that these plates performed well in tests.

The move to provide the military with essentials took place amid the management’s decision to cease the plant’s operation in late February when Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Putting on hold such a large and complex production process like a steel plant is not a one-day job, he said. His staff was cut – of over 20,000 workers at the plant half have been furloughed – but those who stayed were busy with preparing machines for conservation.

“Our workers were not tasked to do it, they themselves started generating ideas of how to produce hedgehogs, spikes, and body armor plates, doing their main tasks in parallel,” Yefimenko said.

Around 2,000 of their coworkers were conscripted into the military so they were eager to help.

“We were in contact with them and checked what they needed,” Yefimenko said.

Olena Pantyukh, a process engineer who has worked for the enterprise for 25 years, is among those who joined Ukraine’s Territorial Defense Forces.

First, she helped the front as a volunteer providing soldiers with humanitarian aid. In May, she decided she wanted to be among soldiers in order to better help Ukraine defend itself from Russia.

“I believe that everyone should put all their efforts toward achieving our common goal. I figured I would be better off there,” Pantyukh said.

“Never in my life have I thought that I would ever put on a military uniform,” she added.

Pantyukh is now responsible for logistics in her territorial defense unit. Her metallurgic colleagues from the mining department are proud of her, she said. The only people she disappointed with her decision are her daughters.

“They strongly demanded that I leave (the country) with them on Feb. 24. I told them that someone should stay here to work and bring our victory closer so that they have somewhere to return,” Pantyukh said.

But it is hard being far away from her grandson, she says: “He is everything to me, he is very little. I am grateful to social media, but there you cannot hug him. It is very difficult.”

She says she is looking forward to getting back to her work as an engineer after the war ends. Until then, 10,000 of her coworkers keep the plant running.

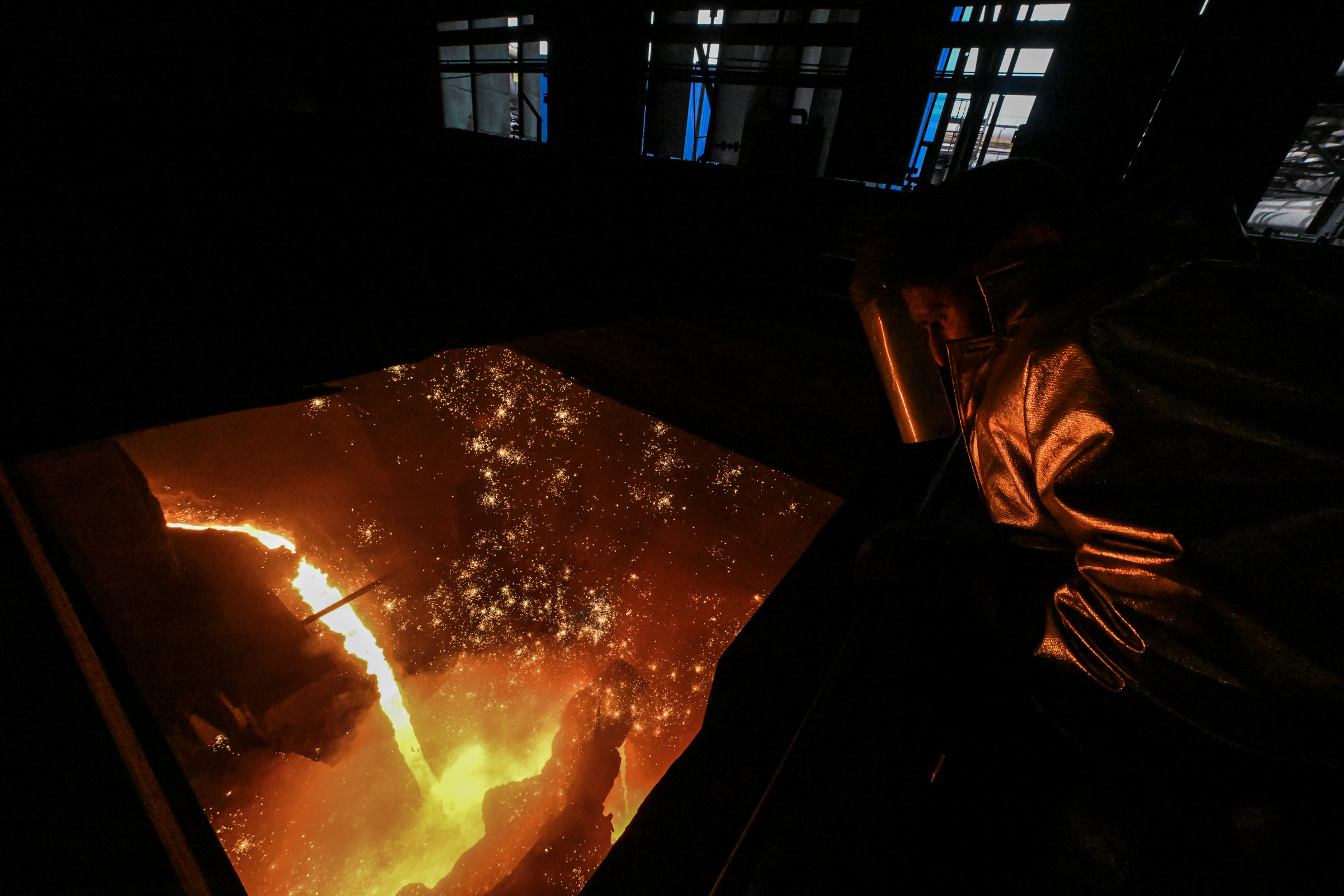

Smelting iron ore

The production partially resumed in mid-April after two months of downtime. The factory is now operating at 25% of its capacity with only one blast furnace out of its three currently up and running. Valery Sorukhan is its shift foreman.

“Production is reduced to a minimum. We make 3,000 tons of crude iron per day in our workshop. We used to make 10,000,” Sorukhan said.

The production is heavily hampered by Russia’s Black Sea blockade.

Before the full-out war, the plant used the seaports in Odesa and Mykolaiv to bring raw materials in and get their products out. Now both the coal that they use for production and the crude iron they sell abroad are stuck in ports.

“Previously, we traded with 115 countries around the world. Our main clients were Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. When the ports became unavailable for us these markets did too,” said Mykola Galushkin, head of the production department.

Read more: Ukrainian grain has nowhere to go as Russian blockade persists

Along with many other Ukrainian producers, ArcelorMittal now uses a railway to take their goods out of Ukraine. The cargo first crosses the border with Poland, then reaches local ports there, before getting shipped further away.

That’s way pricier than trading through national seaports as Ukraine did before the blockade. One reason is that Ukraine’s railway track is wider than that of neighboring European Union countries, which means additional costs for reloading on the border.

Now the plant sells its products to the U.S., Canada, and the EU while trying to explore new markets.

According to Galushkin, for the plant to effectively operate, not only does Russia’s Black Sea blockage have to come to an end, but also Russia-occupied Donbas and Crimea, the sources of raw materials the plant used, must be liberated.

“Before 2014, the plant used coal from the Donets Basin. In fact, the plant was built here for convenience. You have coal to the right and limestones to the bottom. The factory is in between where we have iron ore here. It was ideal, the logistics were clear and well-thought-out,” he said.

Considering the plant’s location, the workers understand why Russia wants it. Looking back at Azovstal, a metallurgical plant in Mariupol, which was under siege for months as it sheltered a couple of thousands of soldiers and civilians, ArcelorMittal employees say they’re prepared for anything.

Read also: Azovstal garrison: ‘We’ll keep fighting as long as we’re alive’

“Our plants are not identical, but similar. I think our factory could become an outpost because there are civil defense facilities, shelters here, too,” Sorukhan said.

They are frequently trained on how to react to all possible war developments. The workers, however, try not to overthink it.

“We try to approach it with humor. If we take it too seriously, it will be very difficult to work here with those constant air raids as we know what could happen if we get hit,” Sorukhan said.

Body armor instead of dresses

This private textile workshop also had to get to adjust to the new wartime reality, get used to working under the constant sounds of sirens and repurpose production.

Before the full-out war, the factory produced clothes by well-known Italian, French and Ukrainian designers. Now it does body armor, military stretchers, and backpacks for hand-held anti-tank grenade launchers.

“We made blouses, jeans, kids’ clothes. We had customers both in Western Europe and in Ukraine,” said one of the factory’s managers Kostyantyn, who did not want to reveal his name for security reasons.

“Then the military administration tasked us with producing military uniforms,” he went on. They have already made a couple thousand uniforms and up to 10,000 body vests.

This meant the factory had to do a lot of reconfiguring: “We had to reprogram our equipment for stiffer, denser fabrics starting from knives, we use to cut things, ending with needles we use to stitch.”

Finding suitable fabrics and sewing tools itself was a challenge. Many producers had their storage facilities in the heavily shelled areas like Kharkiv or Borodyanka and the workshop had to send people there to pick up and bring the goods to Kryvyi Rih.

“The first prototypes of body armor were made of denim…We had some leftovers, so we used it. We used anything that will do,” Kostyantyn said, showing the Kyiv Independent military stretchers with handles made of ribbons in the colors of a well-known Milan fashion house. He does not reveal to the factory’s clients without their permission.

Workers had to adjust, too. Leading technologist Victoria was responsible for recreating the officially approved military uniform. She does not want her last name to be used as her relative is a serviceman: “Everything we sew he wears.”

“The costume is rather complex. It has 92 elements, which is a lot. Ordinary jeans have 16 elements, for instance,” she said.

She has never sewn anything more complicated than this, Victoria confessed: “Before Feb. 24 I would have never thought I could be involved in anything like this.”

They consult with the military about their needs and suggest solutions. The latest device they created is a backpack for hand-held anti-tank grenade launchers.

“The husband of our designer asked to do it. We then gave it to him for testing, and he came back with feedback,” Victoria said.

Many workers have relatives in the military.

Victoria Visloukhova, 35, is new at the factory. Her cousin Serhiy was killed in Donbas back in 2014. When the full-out war broke she wanted to be useful. Having heard of this factory’s new military focus, she decided to join.

“I perform five functions. These are knee pads, I sew Velcro on them so that they do not fall off. I am kind of responsible for the knees of the soldiers,” she said with a smile.

She wants the war to end before Sept. 1, as that’s when her little son Daniil is supposed to go to school for the first time.

“I am looking forward to our victory, very much. Because it must happen for sure,” she said.

____________________

Note from the author:

Hi there. Anna Myroniuk here, the author of this piece.

I traveled to Kryviy Rih to see how its industries are holding on near the frontlines of the war. Due to Russia’s blockade of the Black Sea, these companies are struggling to sell their products abroad. According to the World Bank, Russia’s invasion will shrink Ukraine’s economy almost twice this year. To stay afloat, Ukraine has to be able to participate in trade. By donating to the Kyiv Independent and becoming our patron, you can help us to keep bringing our readers stories that delve into the economic issues facing Ukraine amid Russia's war. Thank you!