‘I’m afraid we’ll never find them:’ Russia holds thousands of Ukrainian civilians hostage

In the early days of the full-scale invasion as Russian troops were occupying large swaths of territory outside of Kyiv, one local village resident was relieved to see what he thought were Ukrainian troops.

The resident, Ivan Drozd, shouted the common Ukrainian salute "Slava Ukraini!" (Glory to Ukraine!) to the soldiers, not realizing they were Moscow’s invading forces.

The Russian troops immediately arrested Drozd on the spot, his partner Hanna Mushtukova told the Kyiv Independent, citing a fellow villager who was arrested with Drozd but later released.

More than 18 months later, Mushtukova doesn’t know anything of Drozd’s whereabouts, except for a short four-word letter she received months after he wrote from a Russian prison.

“Alive. Healthy. Not sick,” the letter reads, Mushtukova told the Kyiv Independent. She hinted he may have been forced to write the letter that way.

Along with war crimes, such as torture, rape, and executions, Russia has also taken civilian hostages in the areas it has occupied, at times transferring them to prisons both in Russian-occupied Ukrainian territory and Russia for reasons unknown. The hostages include people taken off the streets, psychiatric patients, and inmates of Ukrainian prisons now under Russian-occupied territories.

Russia exploits international law loopholes to keep these Ukrainians locked up. Ukraine cannot easily exchange them as prisoners of war, as it would jeopardize millions living under occupation, creating the perpetual threat that any civilian in occupied territory could become a hostage, human rights defenders and officials have warned.

The precise count of adult Ukrainians Russia ensnared as civilian hostages remains elusive.

Ukraine’s Reintegration Ministry says there are 763 civilian hostages in Russia and Russian-occupied areas, while the country’s Ombudsman’s Office puts the number at 20,000. Human rights defenders sharply contest these official figures, suggesting they could be as high as 8,000.

“I'm very afraid that the 8,000 missing civilians include those whom we will never find,” Olga Romanova, the exiled head of Russia Behind Bars, a prominent Russian NGO protecting convicts' rights, told the Kyiv Independent.

“I vividly remember rapidly shrinking lists of missing civilians as all of those mass graves were discovered after Izium’s liberation.”

Drozd was a 28-year-old farmer with no military experience when he was captured and imprisoned by the Russian troops. His partner Mushtukova has no information on his exact whereabouts.

"I'm counting the days. But the uncertainty and anticipation of the unknown are hard to wrap my head around," Mushtukova said.

Sent to Russian prisons

Ukraine’s Coordination Headquarters for Prisoners of War Treatment remains tight-lipped about the count of civilian hostages in Russian custody. Its spokesperson, Petro Yatsenko, told the Kyiv Independent that a meager 140 civilian hostages have returned to Ukraine during several prisoner-of-war exchanges.

Some more managed to return on their own. Mykhailo is one of them, who spent 1.5 years in Russian-run prisons. (Editor’s note: Mykhailo requested his last name be concealed to protect people who spent months in Russian prisons with him)

Serving his prison term in Ukraine since 2019, Mykhailo, 37, was among around 2,000 inmates Russian troops took from a prison in Kherson Oblast following occupation, his lawyer, Anna Skrypka from the NGO Protection for Prisoners of Ukraine, told the Kyiv Independent.

Russian forces sent inmates from four prisons in Ukraine’s south through a series of camps in occupied territories before they ended up in Russian prisons close to Ukraine, according to Srkypka.

From the Ukrainian prison where he had been serving his sentence, Mykhailo was sent to occupied Simferopol, the administrative center of Russian-occupied Crimea. He told the Kyiv Independent that he was taken to a prison housing inmates with tuberculosis even though he was healthy.

A couple of weeks later, the inmates were gathered in the prison’s courtyard and made to stay there the entire day until midnight. Mykhailo says they weren’t given any food or water so they wouldn’t need to use the bathroom on the road to a prison in Russia’s Krasnodar Krai, located across the Kerch Strait from Crimea.

While being transferred, the group spent one night at a prison in Kerch, but Mykhailo says he did not eat for a little over two days until they reached the prison in Krasnodar Krai.

In each new location, the welcome ritual remained unchanged. The Spetsnaz, Russian special forces, would stand in two rows facing one another with their dogs.

Prisoners who had just arrived were made to run down the middle of the special forces as they beat the new inmates with batons and shouted at them to move faster, Mykhailo told the Kyiv Independent.

"The Spetsnaz beat us three times in two days," said Mykhailo.

Inside Russian prison

Mykhailo spent five days in quarantine upon his arrival in Krasnodar Krai. As he was being escorted to the dining hall for the first time after that initial period, he shouted “Slava Ukraini!” (Glory to Ukraine!) to the other inmates. He doesn't remember the duration of the beating he endured for that.

Guards sporadically beat him for war-related disputes with Russian inmates and refusal to obtain Russian citizenship — something the guards frequently asked him to do, he said. Once, he was beaten after arguing with the guards that Russia would not be able to seize Odesa Oblast along with his hometown, Izmail.

When his original prison term imposed by the Ukrainian court approached, conditions deteriorated.

"The last two months were hell,” he said.

Mykhailo said the guards didn't let him sit for weeks, which caused severe swelling in his legs. They would draw billy sticks if they spotted him sitting.

"The last six days (of his time in prison in Krasnodar Krai), they beat us constantly," he said, adding that there was no medical assistance.

The prisons in occupied territories are a “black hole” as it’s “almost impossible” to send real lawyers without Russian Security Service ties there, said Romanova, a Russian prisoners’ rights defender.

Threats to extend his sentence didn’t turn Mykhailo away from believing he could return to Ukraine.

With money sent to him by Skrypka, his lawyer, Mykhailo took a ferry to Russia. It was the only way to return to Ukraine as the bridge over Kerch Strait was closed after a Ukrainian drone attack.

Following a night in a Rostov hostel room full of Russian soldiers returning from the front lines, he bought a box of “good cigarettes” to bribe Russian border guards. It helped him return to Ukraine via the Kolotilovka border crossing, the sole operational link between Ukraine and Russia.

"I was happy to hear the Ukrainian border guard sing in Ukrainian," he said, smiling for the first time as he spoke to the Kyiv Independent.

For Mushtukova's partner, prison conditions are unknown. She neither knows if Drozd has a lawyer nor if he is being charged all.

She said Russia labeled him a prisoner of war without any explanation, even though he is a civilian.

Several hundreds of Ukrainian civilians were arrested in Russia on espionage or sabotage charges after going to the country to visit their relatives or to work. Many of them are sent to detention centers and are deprived of access to lawyers.

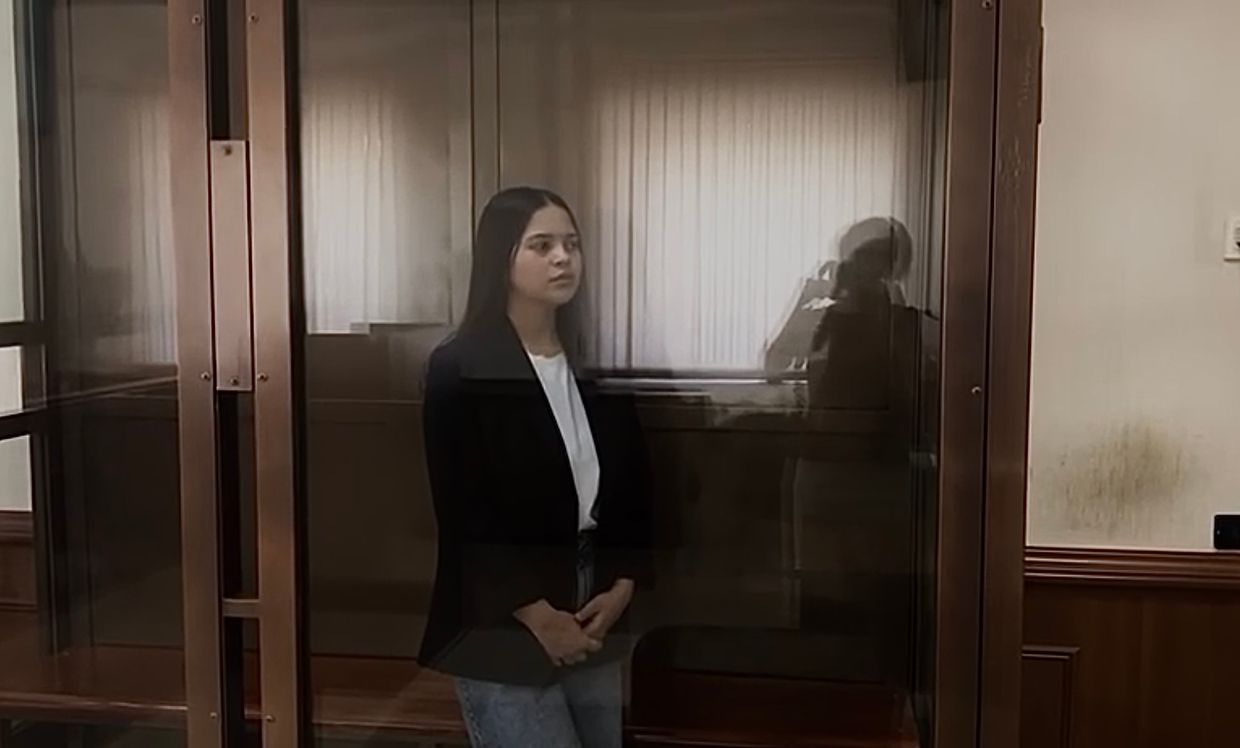

Serhii Karmazin, 45, a civilian Ukrainian who came to Russia to visit his sister after the start of the full-scale invasion, was arrested in February on sabotage charges. The FSB, Russia’s security service, claimed he had set railway equipment in Moscow Oblast on fire and planned to blow up an oil refinery for $1,000 on behalf of Ukraine’s Security Service.

Lawyers have not been able to access Karmazin, who is kept in Moscow’s notorious Lefortrovo Prison, infamous for Joseph Stalin regime purges, and the Soviet KGB jail for political prisoners. Wall Street Journal reporter, Evan Gershkovich, has been held there.

There are “hundreds of people (like Karmazin) who come to Russia for a job or to their families, mostly to work” who have been charged with espionage, said Romanova, a prisoner rights defender.

Romanova and her colleagues cheer when they find a Ukrainian with charges in Russian detention centers. “It means they are alive,” she said.

The fate of many more Ukrainian “civilian hostages” remains uncertain.

“Russia hides Ukrainians after (they are) being sentenced by courts,” Romanova said, adding her Russia Behind Bars NGO traced 460 Ukrainians.

Bringing hostages home

Holding “civilian hostages” constitutes a war crime along with violating several other conventions Russia could be brought to justice for, said Mikhail Savva, a Russian-born legal expert at the Ukrainian human rights organization Center for Civil Liberties.

“If there are no charges against civilians, every party to the Geneva Conventions is obliged to return them as soon as possible,” Savva, a former Russian political prisoner, told the Kyiv Independent.

He said Russia exploits this loophole phrase in the Geneva Convention to keep Ukrainian civilians in legal limbo.

“We can say Russia has a system of war crimes against Ukrainian civilians. Holding a civilian (in custody) for a long term without legal authorization is a war crime of deprivation of liberty and access to justice,” he said.

Meanwhile, Yatsenko, a spokesperson for Ukraine HQ for POWs Treatment, said Russia often does not bother to count “civilian hostages.”

“It hinders finding them while all the powers of the penitentiary system are applied with inhumane traditions of the Soviet Union and Tsarist Russia,” said Yatsenko.

Both Yatsenko and Savva said civilians cannot be exchanged for prisoners of war under international law as it would jeopardize millions of Ukrainians living under Russian occupation.

Human rights defenders suggest amending the international law and sanctioning Russia-run prison heads, Savva said, adding that there is currently no way to coerce countries to return civilian hostages with international law.

To punish Russia for alleged crimes, Ukraine is supposed to notify Moscow of violating international law by holding civilian hostages. Following the note, Ukraine’s Foreign Ministry can appeal to the International Court of Justice if there is no intermediary country to help the parties resolve the issue.

Ukraine’s Foreign Ministry has so far not done so, Savva said.

Mykhailo believes he was lucky to be back home. When he arrived at the central station in mid-August, he embarked on a six-kilometer walk home to feel a freeman.

“Mom met me. We kept silent for a while and then cried,” he said.