Explainer: Why Russia’s nuclear industry has escaped major sanctions

Since the start of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia has repeatedly threatened the use of atomic weapons, yet its much-prized nuclear industry has faced little in the way of meaningful sanctions.

Russia's state atomic corporation, Rosatom, is a key part of the country's military-industrial complex — and is increasingly expanding its reach beyond nuclear weapons. By far the world's largest exporter of reactors and enriched uranium, it is a major player in the global civil nuclear industry.

Despite the significance of the nuclear industry to the Russian state, Rosatom has largely escaped meaningful sanctions. In recent months, the Kremlin has made much of the industry’s 80th anniversary, touting its leadership in everything from rare earth metals to nuclear icebreakers.

Although Russian revenues from the nuclear industry are modest in comparison to the country’s exports of oil and gas, the strategic value of the sector is much greater, not least as one of the few technologically advanced areas of the economy.

Rosatom accounts for almost half of the world's uranium enrichment capacity and currently has seven reactors under construction in Russia and 20 overseas, including two in Iran.

But the company has not faced full blocking sanctions from the U.S., EU, or U.K. — all of which continue to import Russian nuclear fuel or uranium — despite its active role in some of the most troubling aspects of the conflict, including war crimes committed at Ukraine's Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, occupied by Russia since 2022.

The limited U.S. and U.K. sanctions imposed against some Rosatom subsidiaries and personnel leave it less restricted than Russia's heavily sanctioned defense industry. As a result, the corporation has circumvented stricter sanctions against its close partner, Rostec, Moscow’s largest arms group.

Atomic energy on the front lines

Ukrainian nuclear power plants were targeted by Russian forces from the outset of the Feb. 24, 2022, invasion of the country, with Zaporizhzhia the scene of the first military attack against an operating facility in history.

Since then, the plant, Europe’s largest with six reactors, has been under Rosatom control — and remains in a "very precarious" position, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

A disturbing reminder of the perils of disruption to such plants was provided by Russian soldiers’ occupation of the Chornobyl nuclear power plant in the very first hours of 24 February.

The 1986 disaster at the site, widely regarded as foreshadowing the fall of the Soviet Union, was the result of the incompetence of organizations that would later form Rosatom.

The fate of Zaporizhzhia will likely be a major difficulty in any eventual agreement to end the war — as leaving the plant under Russian control would present a severe ongoing risk to Europe, according to recent analysis by the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI).

Europe's reliance on Russian nuclear

The European Union faces a tougher task than the U.S. in disentangling itself from Russian nuclear supplies. The bloc’s extensive nuclear industry has long traded with Rosatom, including supplying it with parts and services required to modernize Russia’s aging fleet of reactors.

The EU, in turn, has long relied on imports of nuclear fuel from Rosatom, which holds a dominant position throughout the complicated production cycle, from uranium mining to fuel fabrication.

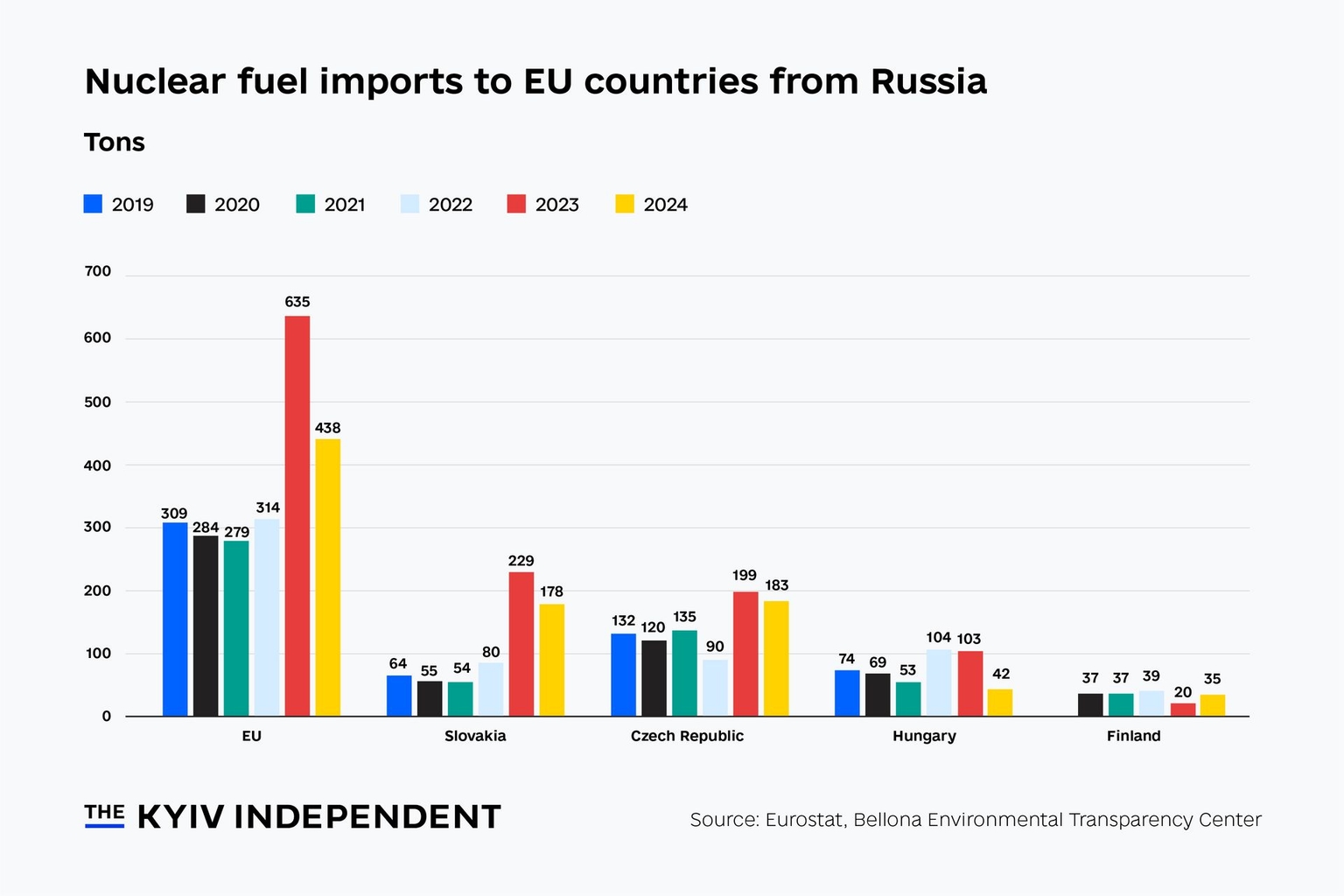

Nearly a fifth of the bloc’s 101 reactors originated in the Soviet Union and require specific fuel assemblies. As a result, imports of Russian nuclear fuel to the bloc doubled in 2023 to 635 tons as operators stockpiled supplies, before falling to 438 tons in 2024, according to the Bellona Environmental Foundation’s latest report on Rosatom.

In 2023 and 2024, the EU spent around 1 billion euros annually on uranium imports from Rosatom entities, according to Bellona.

The bloc is currently working on a 20th package of sanctions against Russia, its head of foreign policy, Kaja Kallas, said on Nov. 14, without giving any further details as to what they might cover.

"The commission is determined to phase out all Russian energy from Europe’s energy system," Anitta Hipper, the EU spokeswoman for foreign affairs and security policy, told the Kyiv Independent on Nov. 21.

"As set out in the Repower EU roadmap, we will present measures targeting Russian nuclear energy as well. Work on these measures is ongoing."

In May, the bloc announced a plan, known as Repower EU, to phase out reliance on Russian energy, including nuclear, for good. Unlike sanctions, the legislation does not require the unanimous approval of member states.

The political and economic costs of imposing sanctions on Rosatom vary significantly across the West, as well as between EU members, according to George Voloshin, an expert on Russian affairs and sanctions.

"A comprehensive ban would force rapid, expensive, and politically painful procurement and conversion efforts," Voloshin said.

"Consequently, any EU sanctions would likely target new contracts or specific technology transfers, rather than the current fuel supply."

The five EU members that operate Soviet-era reactors — Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, and Slovakia — have all taken steps to reduce reliance on Rosatom, with the exception of Hungary. Budapest has actively opposed sanctions against Russia and is pressing ahead with a Rosatom project to expand its Paks nuclear power plant with two new reactors.

Ukraine, on the other hand, has taken a much tougher tack against Rosatom. Kyiv has managed to completely cut ties with the corporation while keeping 60% of its fleet of 15 Soviet-designed reactors operational, according to the World Nuclear Industry Status Report (WNISR) 2025.

No other country besides Ukraine has imposed full sanctions against Rosatom, despite consistent calls from Kyiv.

U.S.-Russia nuclear relations

For decades, the U.S. has relied heavily on Russian imports of enriched uranium to fuel its fleet of 94 operational commercial reactors, the largest in the world.

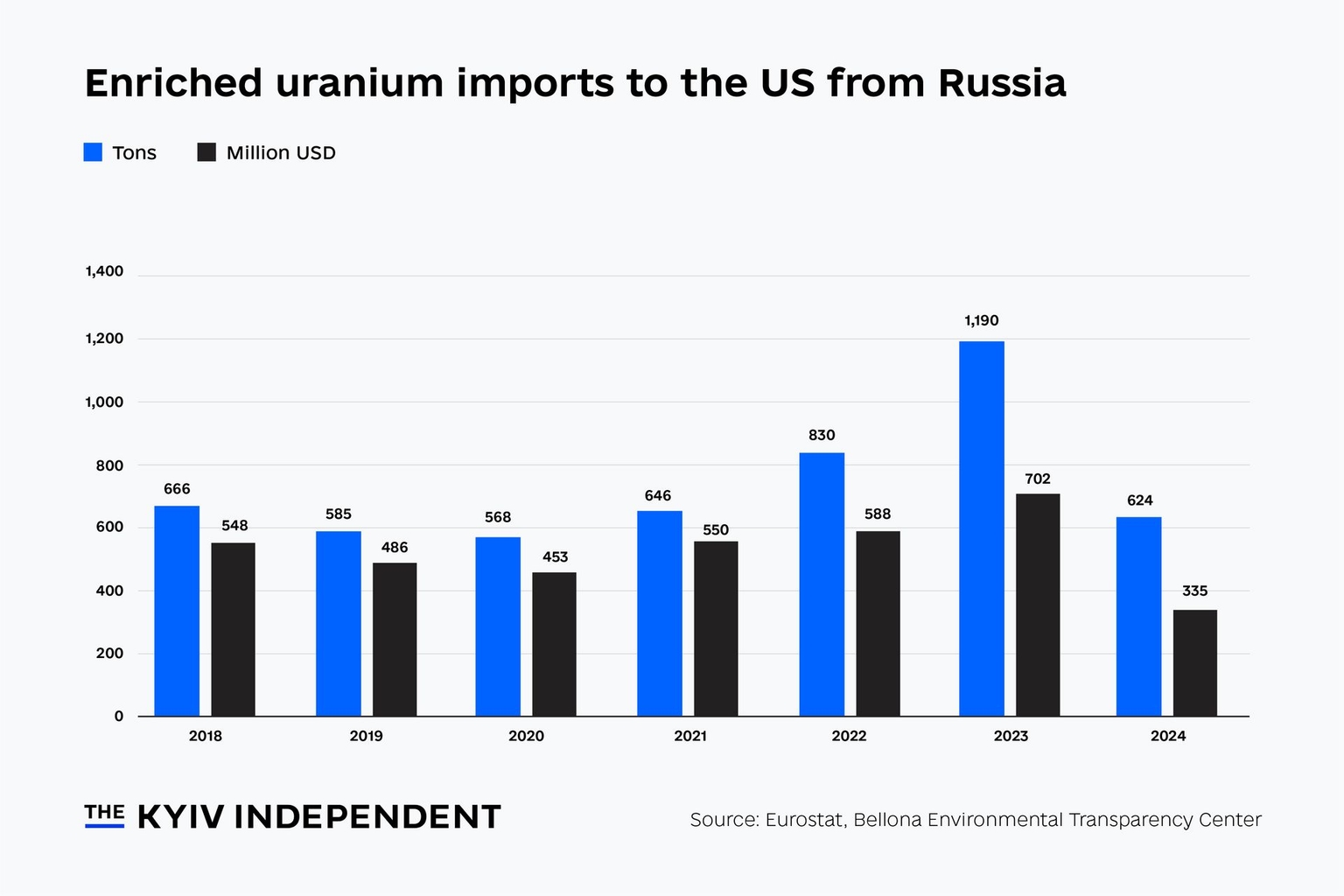

While imports of enriched uranium from Russia were banned as of August 2024 under the previous presidential administration of Joe Biden, enforcement has been limited by conditional waivers until 2028 to prevent supply chain disruption.

In anticipation of the ban, imports of enriched uranium surged in 2023 to a value of over $1.2 billion, before falling to some $624 million in 2024, according to Bellona.

The legislation also contained provisions to release $2.7 billion in funding for domestic production and procurement of enriched uranium from non-Russian sources.

Since returning to office, President Donald Trump has vowed to reinvigorate the country’s diminished nuclear industrial base and tackle dependence on imports of uranium on grounds of national security.

Although Trump has in recent months responded more aggressively than Biden to threats of nuclear war from Moscow, he has so far declined to strengthen measures against Rosatom. In July, Trump said he had ordered American nuclear submarines to be repositioned in response to what he called "highly provocative" comments by former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev.

"Numerous Rosatom subsidiaries are subject to U.S. sanctions," a State Department spokesperson told the Kyiv Independent on Nov. 28. "All Russian-related sanctions and authorizations remain in effect. We expect countries, companies, and individuals to comply with U.S. sanctions."

With Moscow and Kyiv still far from a mutually acceptable peace deal, Rosatom could present a tempting target to pressure the Kremlin — as Trump looks to finally fulfil his promises of ending the war.

"The most severe option would be blocking financial sanctions on Rosatom itself," according to Voloshin.

"This would paralyze the corporation by cutting it off from the global financial system and U.S. dollar transactions, halting payments for foreign contracts, financing, and (joint ventures)."

Export controls on specific advanced components and dual-use technologies could also slow down or even halt the construction of new plants overseas, Voloshin added.

With lucrative Western markets slipping away, Russia is looking to the developing world for future expansion. The long-term nature of nuclear projects fosters deep dependence, offering Moscow new channels of influence.

In 2024, Rosatom earned about $18 billion from overseas projects, including roughly $4 billion from countries Moscow labels "unfriendly," the head of Rosatom, Alexey Likhachyov, told the Russian parliament in May. Rosatom’s portfolio of long-term foreign orders stood at over $200 billion in 2024, according to Interfax.

Another option, according to Voloshin, would be sanctions against new contracts with Rosatom, preventing Western firms from working with the company and limiting future revenue. The measures would "specifically target the lucrative long-term commitments that form the basis of its geopolitical influence," he said.