Forced conscription in occupied Ukraine pushes essential services to brink

In December of last year, the icy showers that rain down on Ukraine’s eastern Donetsk Oblast in winter caused the usual damages: falling branches severed power lines, causing electricity, water, and heating outages.

Except there were fewer people to do the needed repairs. Russia’s forced mobilization campaign in the Ukrainian territories it occupies has severely depleted the workforce, hollowing out municipal services.

As the Kremlin continues to conscript local Ukrainians, the shortage of essential workers is only expected to worsen. Conditions have gotten so bad that Ukraine’s military intelligence says that resistance to Russia in occupied territories has seen a recent increase.

Locals in the occupied territories regularly take to chats on the Telegram messenger app to lament the lack of running water and electricity, burst heating and sewage pipes flooding the basements of multi-story buildings, and growing garbage heaps.

In another example of the lack of services, a video posted to a local Telegram channel shows people in a neighborhood of the Russian-occupied city of Donetsk walking along a road as cars weave between huge potholes. At least 10 bus routes in Donetsk have been canceled in recent months, according to both locals and the Russian occupation authorities.

"The problems we see in the occupied territories are related to the crisis in municipal or urban engineering services,” Kostiantyn Batozskyi, the director of the Azov Development Agency and a Donetsk native, told the Kyiv Independent.

“They stem from the fact that there are no people, not enough repair teams, locksmiths, and basic skilled workers because they have all been conscripted,” he said.

Russia has forcibly conscripted an estimated 65,000 Ukrainian men in occupied Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts since the start of the full-scale invasion in 2022, according to Ukraine’s military intelligence. Forced conscription under occupation constitutes a war crime under international law.

Many of them are expected to have been killed in action as Russia reportedly uses these men as cannon fodder. Their absence is felt across the workforce in occupied regions.

“At some companies, they have conscripted up to 80% of the men,” Director of the Institute of Strategic Research and Security Pavlo Lysianskyi told the Kyiv Independent.

Meanwhile, Russia heavily underinvests in occupied Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, parts of Ukraine under Moscow’s control since 2014, extracting resources and using the area to build up its military infrastructure for its war against Ukraine.

And Russia is expected to mobilize even more men. In early January, the Ukrainian military reported Russia's plan to force teenagers aged 17 in all occupied regions to register at Moscow-controlled military enlistment offices.

"(Russia) gathers mobilization resources. Thus, (municipal) issues are expected to escalate," Lysianskyi said.

Lack of investment

Oleksandra, a Donetsk resident, shared a video with the Kyiv Independent of water streaming down the walls of her apartment from a decaying roof of a five-story building in the western part of the regional capital. It wasn’t the first time.

"(Repairmen) patched up the leak after the water had been flowing for several days. But it's not a comprehensive repair," she said.

Russian propaganda waves around downtown Donetsk as proof everything in the area is running smoothly, observers say, while at the same time, Russia and its proxies claim that the war has made it too dangerous to enter certain areas for repairs.

Russia attributes all the problems of the occupied regions to the war, said Stanislav Fedorchuk, who heads the Ukrainian People's Council of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, a Kyiv-based NGO consisting of internally displaced people from occupied Ukraine.

"Look at Russian regions that are essentially colonized territories. There are massive problems with municipal services as well. This shows what Russia has truly brought to the occupied territories — forced mobilization and the destruction of infrastructure," Fedorchuk told the Kyiv Independent.

Infrastructure that Russia doesn’t appear to have big plans to fix. In its budget for 2024, Russia reportedly allocated a mere $178 million for reconstruction and infrastructure in the occupied territories. Moscow didn’t specify the plans.

At the same time, Russia is planning on spending six times more—$1.1 billion—to fortify and develop its grip over the occupied territories of Ukraine by creating new regional government offices, establishing regional investigative committees, and general prosecutor's offices, according to Russia’s 2024 budget.

Meanwhile, in one direction, Russian workers head to the occupied areas, and trains carrying coal, metal, and grain during the summer are going the other way, to Russia.

"200-500 carriages depart daily. (The Russians) have people handling these logistics," said Lysianskyi.

As the civilian infrastructure crumbles and local men perish in the war, Russia is importing its own citizens to build up military facilities in the occupied territories.

Russia is converting the Ukrainian regions they seized into an extensive military base, establishing military units, and creating training grounds, said Lysianskyi.

To support these endeavors, Moscow is developing a highway from Russia’s city of Rostov straight to occupied Crimea, threading through key logistic and military hubs for the Russian army in southern Ukraine, Mariupol, Berdiansk, Melitopol, Henichesk, and Djankoy.

Increased resistance

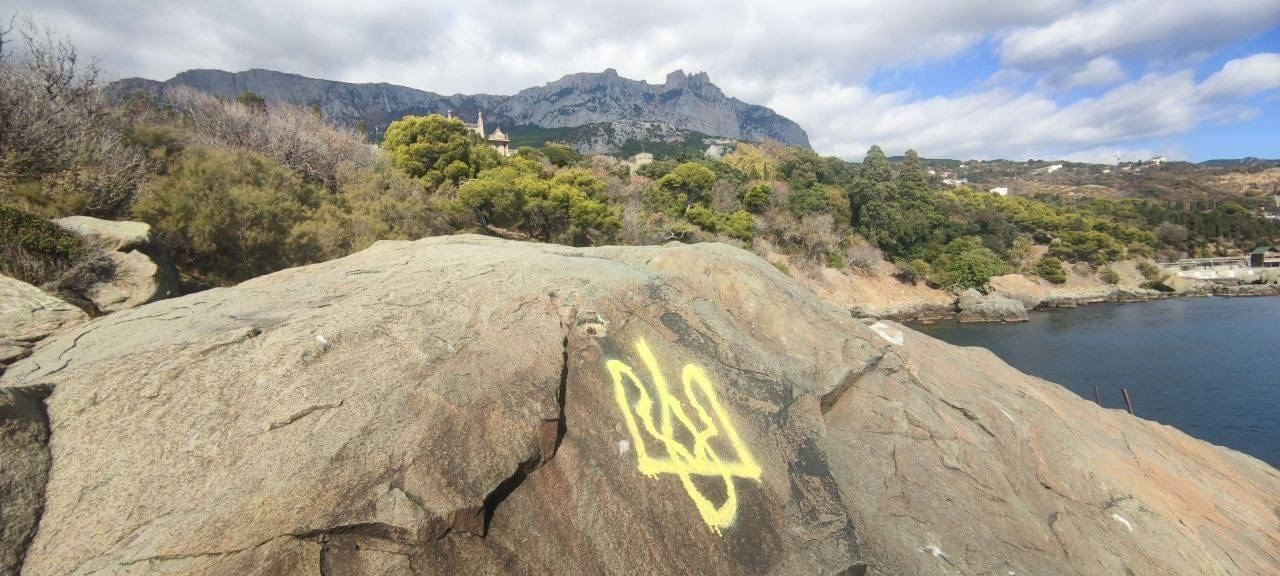

The dire conditions are pushing more Ukrainians under occupation to turn against Russian forces.

According to Fedorchuk and Batozsky, a growing number of Ukrainians in the occupied areas are now actively helping Ukrainian forces with tracking the Russian military and sharing their locations.

Ukraine’s military intelligence (known by its Ukrainian acronym HUR), has also observed a similar trend.

Andriy Yusov, a spokesperson for HUR, told the Kyiv Independent that forced conscription campaigns and local issues “had become an additional motivation” for Ukrainians under occupation to help the defense forces.

Despite a contingent of 35,000 personnel of Russia’s National Guard deployed in occupied Ukraine, Moscow-installed administrations requested additional personnel, including from the Security Service, FSB, and other special services to control the local population, Yusov said.

"They cannot fully combat our underground resistance," a spokesperson for Ukraine’s military National Resistance Center, who didn’t provide his name due to security reasons, told a news briefing in Kyiv on Jan. 17.

More Russian silovikies, the Russian term for state-run law enforcement agencies authorized to use force against civilians, will lead to yet another Russian wave of pressure and repression against the locals in the occupied Ukraine, the National Resistance Center said.

"Ukrainians understand that the only liberation army is Ukraine’s Armed Forces," said Fedorchuk.