Chart of the week: Can Ukraine's nuclear sector move past its Russian heritage?

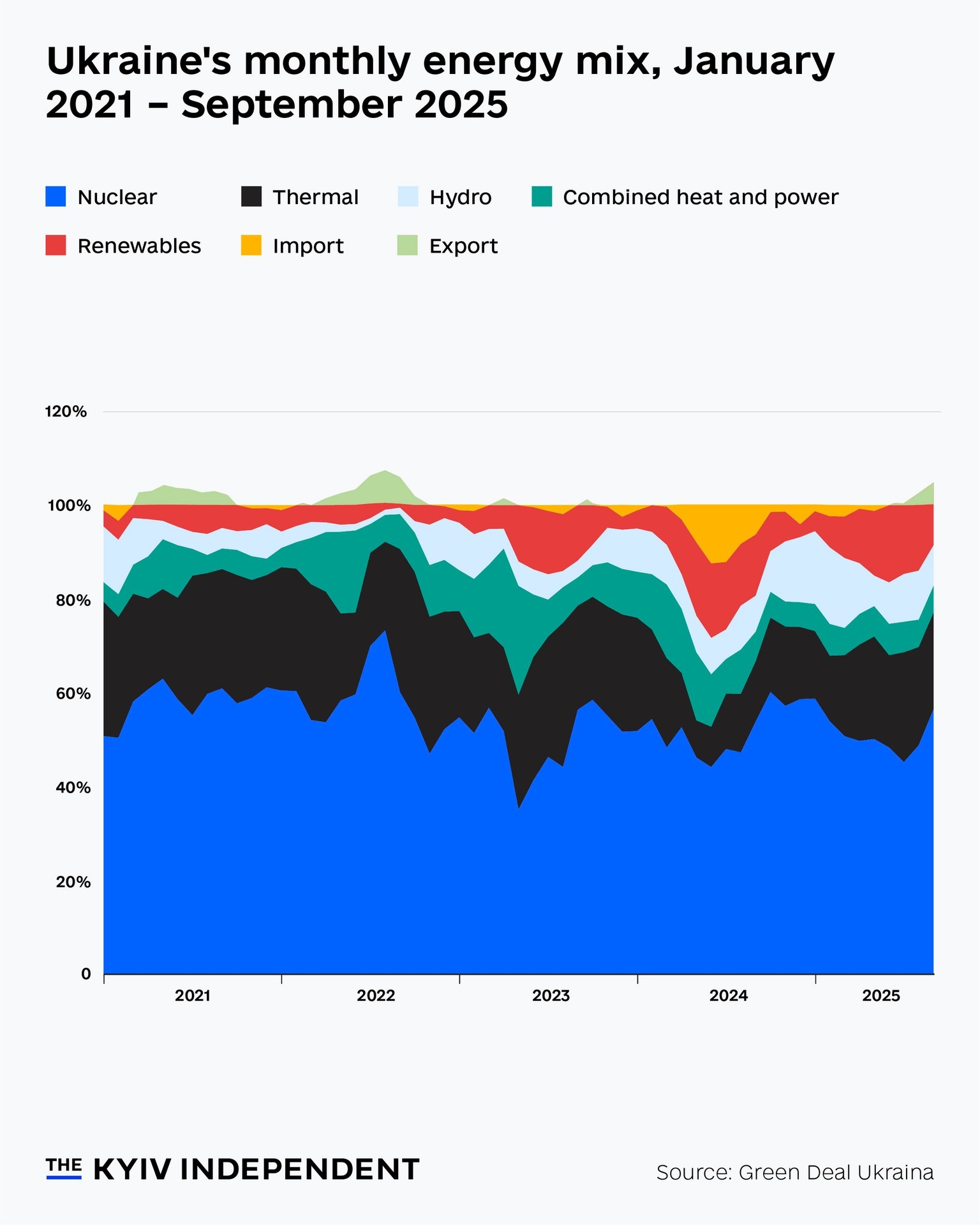

Nuclear power has always been the bedrock of Ukraine's energy system, consistently providing roughly half of the country's power both before and after the start of Russia's full-scale invasion.

But beneath this veneer of stability is a sector in flux.

The biggest corruption scandal of Zelensky's tenure, weak governance, and the relentless barrage of drones and missiles targeting the distribution network are just some of the recent woes engulfing the country's state-owned nuclear monopoly, Energoatom.

And despite efforts, the sector remains burdened by an entrenched, longstanding reliance on Russia.

"The nuclear sector always had deep Russian influence," says Olena Pavlenko, president of Ukrainian energy think tank Dixi Group, who spoke to the Kyiv Independent on the sidelines of their annual Energy Security Dialogue conference held in Kyiv on Dec. 9.

"We used their reactors, enriched their fuel, and there was a lot of communication between Russian and Ukrainian scientists," said Pavlenko.

Ukraine is hardly alone in depending on Russia in this sector. The EU is reliant on Russia for multiple aspects of nuclear power, including reactors, fuel, and services — importing 38% of its enriched uranium from Russia, according to a recent report from think tank Bruegel.

The EU now has a roadmap to diversify away from Russian nuclear energy. But Ukraine started the same journey several years ago.

In the aftermath of Russia's annexation of Crimea and occupation of Donbas, Ukraine took steps to diversify away from Russian nuclear fuel, converting its Soviet-era reactors to be able to use fuel from American company Westinghouse — the first country in the world to do so, according to Energoatom. Since 2020, Ukraine has not purchased Russian fuel.

But Ukraine's path away from Russian energy has not been linear.

Some in the country — including President Volodymyr Zelensky — have pushed for the Khmelnytskyi nuclear power plant to be expanded by purchasing two Russian nuclear VVER-1000 reactors from Bulgaria.

Proponents of the plan say it's a panacea, offering to meet Ukraine's future electricity needs for the bargain price of 600 million euros ($700 million) that Bulgaria offered for the older nuclear generators. But the project has come under scrutiny.

"All experts in Ukraine said that building additional nuclear power plants with Russian nuclear reactors is counter to building our energy independence," Pavlenko said.

Bulgaria backpedalled from the sale earlier this year, ultimately making Ukraine's decision for it.

But with nuclear power expected to continue to constitute a large share of Ukraine's energy mix in the future, the question of how Ukraine can move beyond its Russian heritage remains open.

Beyond improving Energoatom's governance, making procurement practices more transparent, and reforming management at individual nuclear power plants, Pavlenko says that fostering ties abroad is crucial for charting Ukraine's own course.

Ukraine's nuclear sector has not always taken the initiative. Pavlenko highlighted that few in the sector speak English, which is a barrier to developing deeper cooperation and communication with companies, research institutes, and government bodies globally.

"We need to bring fresh blood to the sector that wants to build cooperation abroad — it's not hard to build a network, we just need people who are ready to do that."