What danger does Transnistria pose to Ukraine, Moldova?

Statue of Vladimir Lenin seen in front of Presidential Palace in Tiraspol. Tiraspol is the capital of Transnistria, a Russian-controlled breakaway state in Moldova. (Diego Herrera/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

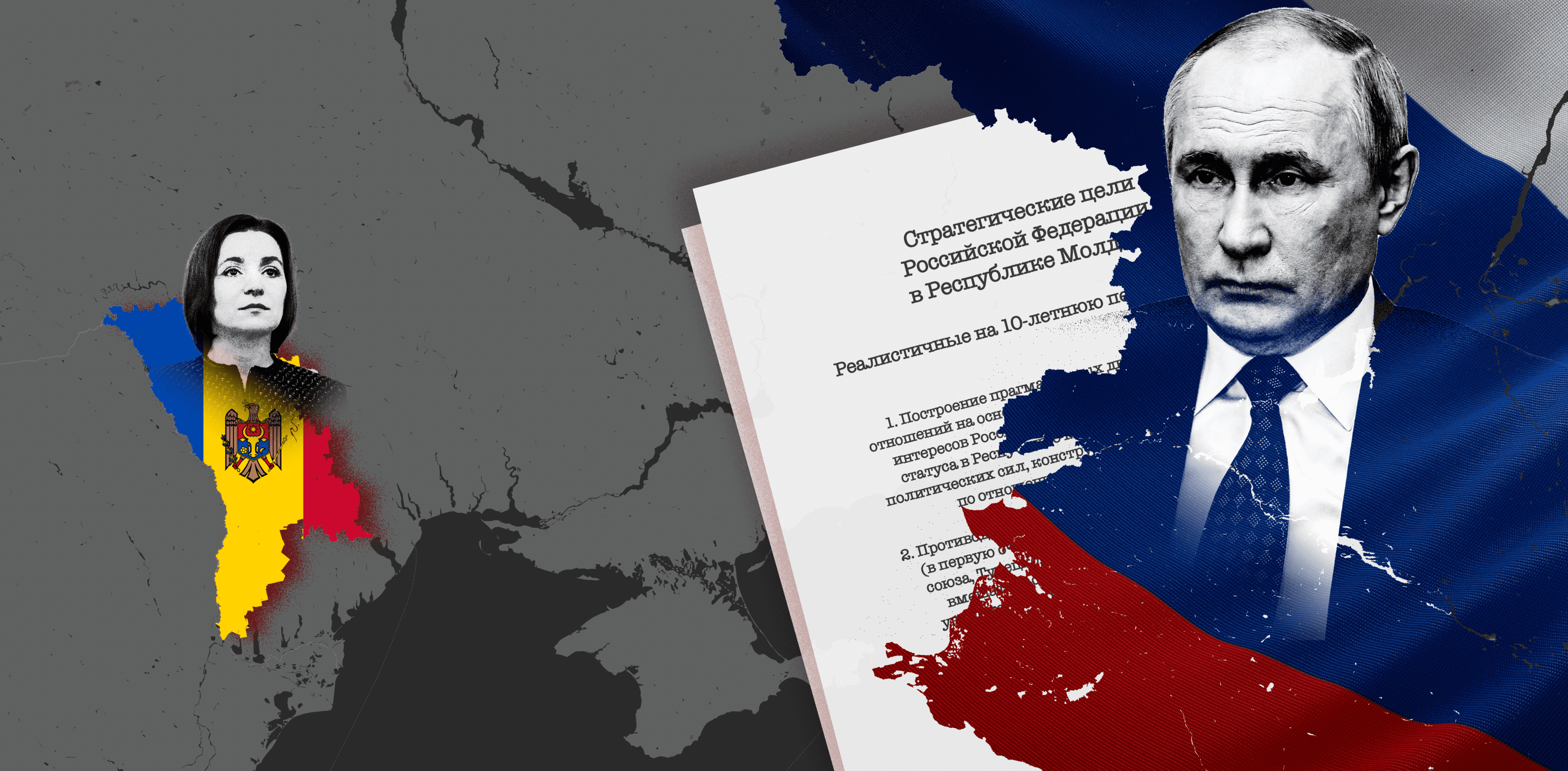

When there was no mention of Transnistria — Moldova's Russia-led breakaway region — in Vladimir Putin's speech on Feb. 29, Moldovans sighed with relief.

A day prior, the leaders of the unrecognized breakaway entity, sandwiched between Ukraine and Moldova, had asked Russia for "protection" — a plea that some saw as an invitation for Moscow's covert attack against Chisinau.

There were fears that the Kremlin would repeat the February 2022 scenario when it recognized the "independence" of the Russian-controlled militant groups in eastern Ukraine to justify its all-out war against the country launched a few days later.

As Moldova is preparing for highly contested elections in October, and the pro-Russian opposition is seeking to increase its standing, experts agree that Russia can use the highly dependent region to increase the threat for Kyiv and Chisinau.

Plea for protection

There are several interpretations of what happened at the so-called "all-deputies congress" in Tiraspol, Transnistria's capital, on Feb. 28.

The gathering passed seven resolutions to Moscow, as well as the UN, OSCE, the European Parliament, and the Red Cross, asking them to stop the "pressures" coming from Chisinau.

Since Jan. 1, Transnistrian businesses trading with the EU are compelled to pay duty to Chisinau. With the trade between the EU and Transnistria reaching 70% of the entity's total turnover, the Russian-influenced region saw its customs revenues plummet.

Moldovan President Maia Sandu dismissed the Tiraspol congress' plea as an attempt to "ask for money.

Former minister for reintegration, Alexandru Flenchea, added that the monopoly of Sheriff, the largest enterprise in the breakaway region that controls everything from petrol stations and shops to TV channels and factories, is incompatible with further economic reintegration with Moldova.

But, the Moldovan government saw events in Tiraspol not simply as an economic protest but as a "Russian psyops."

The Transnistrian political elite has at least two known factions — the pro-Russian group led by "foreign minister" Vitaly Ignatiev, who holds a Ukrainian passport and is suspected of treason in Ukraine, and the Sheriff-linked group led by "president" Vadim Krassnoselsky and Sheriff founder Victor Gushan, who have EU passports and properties in Ukraine.

According to Moldovan analyst Victor Ciobanu, the plea for protection could have been a balancing act to put pressure on Chisinau and Kyiv but not to invite military action from Moscow.

Despite the fact that Moscow agreed to withdraw its army from Transnistria in 1999 at the OSCE Istanbul summit, Russian troops are still stationed in Transnistria.

But most of these 1,500 soldiers are locals and could be easily outnumbered by the Ukrainian army.

Yet there was a plan to demand more from Russia, going as far as a request for annexation, Ciobanu said. "Russia is irrational," he added.

On Feb. 20, opposition politician Ghenadie Ciorba, a former "minister of communication" in Tiraspol, leaked the plan to the wider public.

"I noticed an attempt to try and cover up this failure, as the (pro-Russian) Socialists party (in Chisinau) immediately announced energy tariff protests," Ciobanu said, explaining this as an attempt to draw away attention.

Kremlin-linked Moldovan politician Renato Usatii demanded snap elections.

However, the majority of the people living in Transnistria are not supportive of increasing the level of conflict.

According to Chisinau, about 340,000 people in Transnistria, 97% of the region's population, hold Moldovan passports. Meanwhile, about 220,000 people also have Russian documents, according to Tiraspol.

"The passport queues at the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine showed that people in Transnistria do not want war and that the Moldovan passport is more attractive for them now," Ciobanu said.

Moldova's mounting problems

After the start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Moldova has been walking a fine line. On one hand, Chisinau supported Ukraine and tailed Kyiv's move toward the EU. On the other hand, Moldova did little to provoke Russia, holding enormous sway over the country.

And with presidential elections and a foreign policy referendum scheduled for October, the country is awaiting Russian-led political turmoil.

"What we've seen in Transnistria was a show put on so that the Kremlin has a reason to disrupt the situation in Moldova, particularly the upcoming referendum on whether Moldova wants to join the EU and the presidential elections," Moldovan lawmaker Oazu Nantoi of the pro-European ruling party PAS told the Kyiv Independent.

"We will see the meaning of this show later on," he said, adding that while Ukraine continues to fend off the Russian onslaught and there is no direct corridor for Russia to reach Transnistria, there is a limited scope of how the Kremlin can use Tiraspol.

Experts agree that the crisis in Transnistria is set to help influence the upcoming elections, where pro-European incumbent Maia Sandu is set to see a runoff with one of the pro-Russian candidates, possibly her predecessor Igor Dodon, head of the Socialists Party, Chisinau Mayor Ion Ceban, who now claims he is pro-European, or former Governor of Gagauzia Irina Vlah.

"If a pro-Russian government comes to Chisinau, that would be a catastrophe for Ukrainians because it would open a second front," Ciobanu alleged. "Transnistria was created artificially in 1990 as a thorn not just in Moldova's rib but also in Ukraine's," he added.

Pulling Moldova apart

Unlike other Russian-controlled or occupied regions, Transnistria's dependence on Moscow is more economic and political than military.

After helping the breakaway region fight the government in Chisinau, Moscow kept a small illegal military presence in Transnistria, enough to keep pressure on Moldova. Yet, having no border with Tiraspol, Moscow focused on economic and political mechanisms of control.

Moscow kept supplying Transnistria with "free" gas and blackmailing Chisinau to pay for the "debt." Transnistria unilaterally adopted the Russian flag as one of its "national" symbols and kept the Soviet hammer and sickle on its own flag.

When election campaigns in Moldova pick up the pace or Chisinau gets closer to Brussels, Russia increases economic and political pressure on the country through the region, not forgetting to saber-rattle.

Russia uses a similar tactic in another Russian-friendly Moldovan region – Gagauzia, located further west of Transnistria and home to 130,000 people.

According to Ciobanu, Gagauzia would have followed in Transnistria's footsteps had Tiraspol asked to join Russia. Gagauz independent journalist Mihail Sirkeli said there was an attempt to "provoke" Chisinau to interfere in Comrat, the region's capital, to create a precondition for more escalation.

In recent years, the EU has invested more than 100 million euros to build infrastructure and help repair Gagauzia's kindergartens, schools, and state institutions.

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Transnistria too has increased its trade with the EU.

More and more people from Transnistria commute to work in Chisinau, which is located 70 kilometers west of the breakaway region.

In the first weeks of Russia's full-scale war against Ukraine, people living in Transnistria formed queues to renew their Moldovan passports in order to be able to flee to Europe if war also came to Moldova.

"A victory for Ukraine would mean an end to the Transnistrian conflict," Ciobanu added.