‘The Ukraine’ book of stories offers a look at different, pre-war Ukrainians

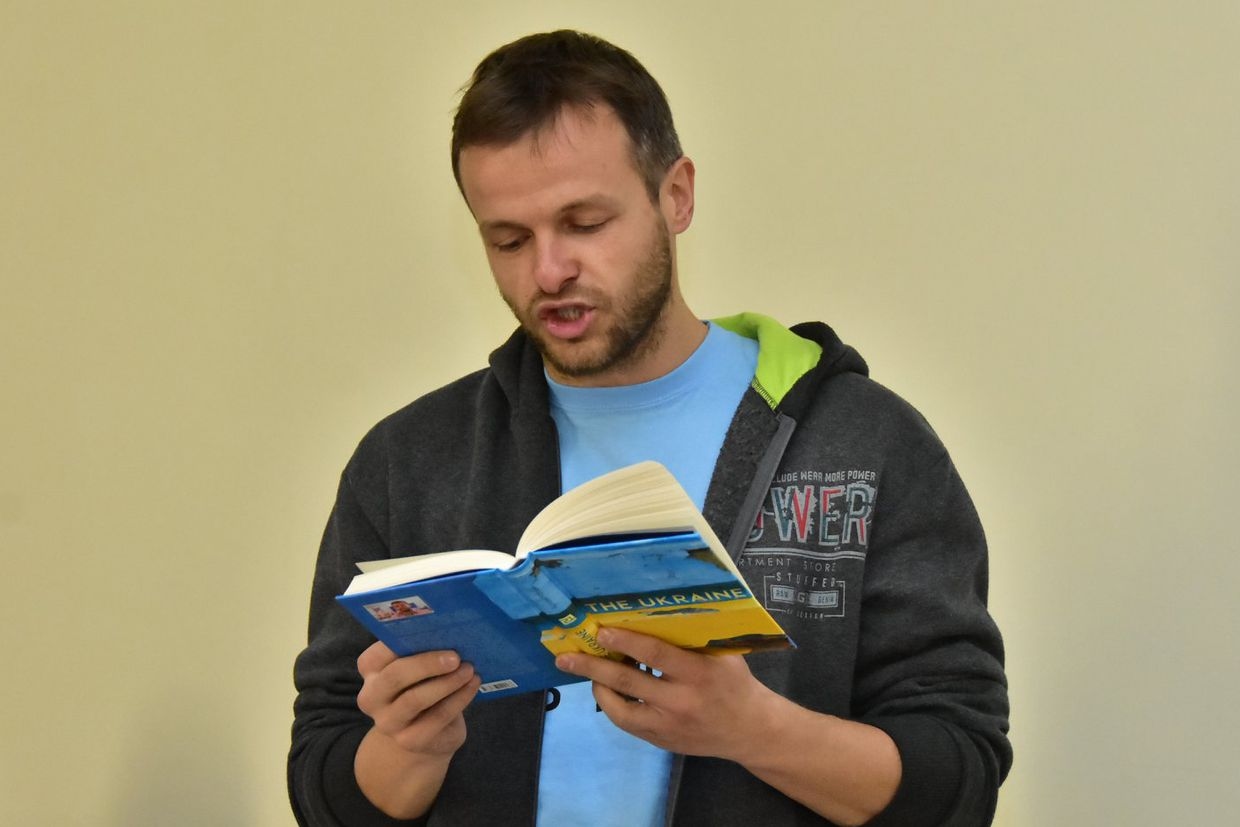

Ukrainian author Artem Chapeye has lived many lives: journalist, activist, translator, and since the spring of 2022, a soldier in the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

Being a writer helps him to “endure everyday army life,” he said in an interview in June 2023, but “until everything is finished, it is very difficult to write something” about Russia’s full-scale invasion. “There is a feeling that there are not enough words for this.”

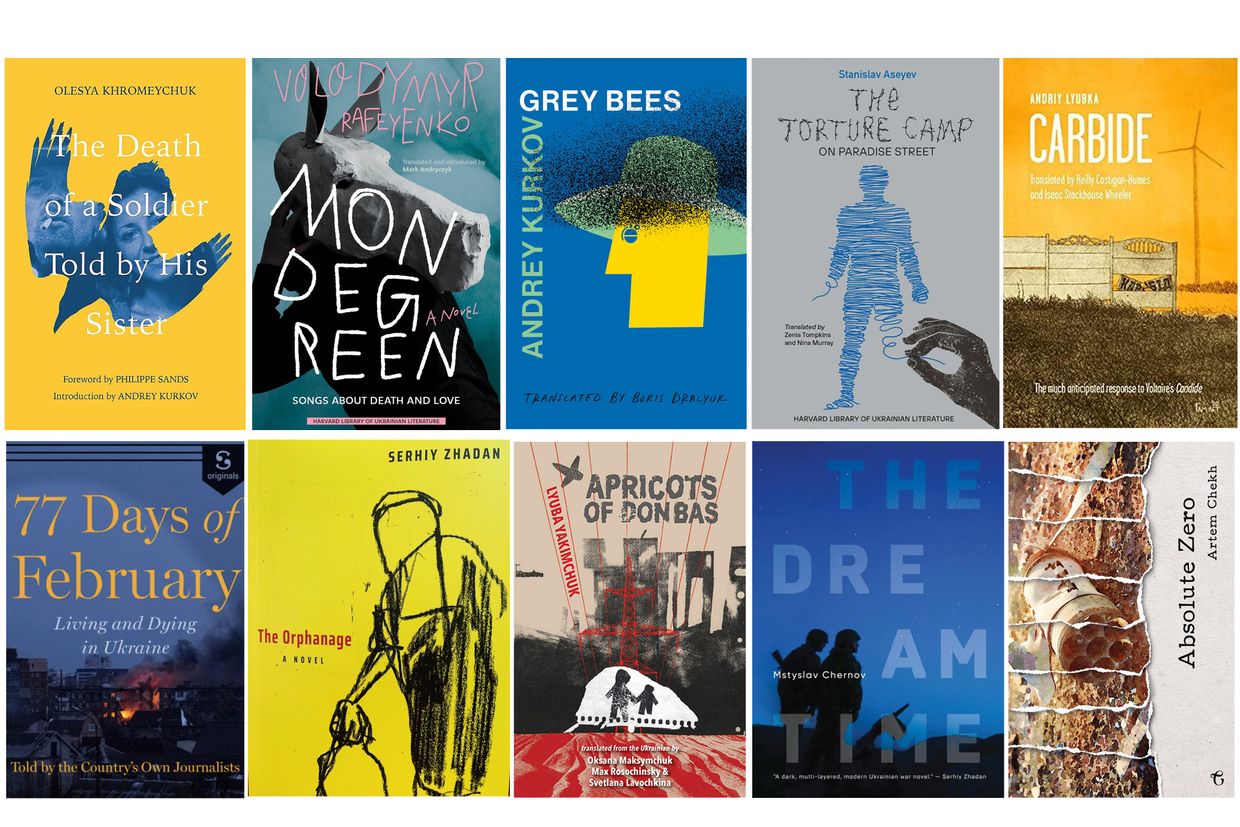

Before 2022, Chapeye had published over a dozen works of fiction and non-fiction. His 2018 book “The Ukraine” has now been translated by Zenia Tompkins and is the first to be published in English.

The collection of 25 fiction and creative nonfiction stories paints a picture of a country with deep complexities and contradictions that do not fit into simple headlines, and the book’s title is an ironic nod to the way foreigners often mistakenly refer to it. Upon original publication, “The Ukraine” was soon included on lists of the best books of the year by BBC Ukraine, Ukrainian Book Institute, and PEN Ukraine.

It was first published in a very different Ukraine to that of January 2024, a country where comedian Volodymyr Zelensky had not yet announced he would run for president. Four years before the publication of “The Ukraine,” Russia had annexed Crimea and installed proxy forces in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. It would be another four years before Russia would launch its full-scale invasion.

Chapeye wrote the stories between 2010 and 2018 and based many of them on his own experiences. The book therefore captures a particular zeitgeist in Ukraine’s recent history, shown through his perspective and the eyes of ordinary people.

“The following stories are possibly based on real events,” Tompkins’ translation note reads. The original text was written in standard Ukrainian, Russian, a mix of the two known as “surzhyk,” and regional dialects. She emphasizes that “this is the Ukraine Russia invaded on Feb. 24, 2022.”

“The Ukraine” sets out to provide a glimpse into the life of someone you could bump into in the Kyiv metro or overhear talking on a village street. While the stories often have a simple premise, Chapeye has a talent for digging into the layers of humor, tragedy, and melodrama of modern life.

He has an intense interest in the mundane, managing to transform an everyday encounter into a piece of theater. The characters in “The Ukraine” almost always have their own title, as if they are each acting in their own play: truck driver, forest keeper, policeman, student, courier, real estate agent, market worker.

For Chapeye, each ordinary person is “an entire universe, a gigantic cosmos brimming with internal stars.” Even in the shortest of stories, he is able to sketch out their motivations, hopes, and dreams, reminding the reader that everyone sees themself as the main character in their own life.

Chapeye does not pretend to be a neutral observer of his country and often provides the reader with a clear signal as to his political beliefs. In one story, he demonstrates his disinterest (bordering on disgust) with the rich, famous, and powerful upon encountering an influential family. He describes feeling embarrassed to be seen in their presence, viewing himself as “shamelessly a part of the crowd.” Instead, he is determined to tell the stories of vulnerable Ukrainians, pensioners, internally displaced people, and the workers the state has left behind.

“The Ukraine” features numerous stories of the elderly trying to survive on “Soviet pensions” in a post-Soviet country. They have a deep distrust of those around them, sometimes even their own family members. There is an even deeper distrust of the government, regardless of which president has been elected. Chapeye references this mentality, that people “upstairs” are making the rules and “robbing” those below, in multiple stories, featuring characters ranging in age, occupation, and region.

The stories span the breadth of Ukrainian territory, from Donbas, an industrial region comprising Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, in the east to the Carpathian Mountains in the west. While many stories are fictional, Chapeye’s experiences driving his motorcycle around Ukraine clearly provided much of the creative non-fiction material for “The Ukraine.”

The book does not shy away from addressing the regional stereotypes that Ukrainians assume about one another, a theme that does not neatly fit the post-2022 narrative of a united country. Chapeye occasionally conceals the fact that he is from the western Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, not wanting to be labeled a “Banderite,” after controversial Ukrainian nationalist leader Stepan Bandera, who was demonized by the Soviet authorities.

Those in the east, meanwhile, are labeled “Muscovites” by those in the west, who perceive them as pro-Russian. One character from a village close to the Moldovan border in west-central Vinnytsia Oblast complains that he is labeled both, depending on whether he travels east or west.

In another hint to his political views, Chapeye appears to most enjoy the company of the “Makhnovites” of Zaporizhzhia, where Ukrainian revolutionary Nestor Makhno led an anarchic movement between 1918 and 1921. He also notices a distinct regional culture, as “people here are constantly joking around,” in comparison to the “proletarian directness” of neighboring Donbas. “You can breathe so freely here in these steppes!”

Before 2014, Chapeye spent years riding his motorcycle around parts of southern and eastern Ukraine, places that have since been invaded by Russia. On the road, he references towns whose meanings have since been irrevocably changed by Russia’s army, such as Soledar, Debaltseve, or Pokrovsk.

Places that are now covered in minefields and mass graves were once pitstops for Chapeye on motorcycle adventures. “The Ukraine” shows that eastern Ukraine was not always battlefields and occupied territories, but where acquaintances might live, or where friendly locals could help you fix a motorbike.

“To which side of all this did you get carried,” Chapeye later wonders of a truck driver he met before 2014 in Luhansk Oblast, unsure whether he remained loyal to Ukraine. Chapeye’s phrasing removes any sense that the man could be blamed for the side he may have chosen.

In the last third of the book, his own experiences reporting on the war in Donbas come to the fore, and the fiction stories give way to what feels more like a journalist’s memoirs. Chapeye meets a range of characters, some of whom he returns to, each of them with their own trauma and inconsistencies.

Outside Ukraine, February 2022 is now often referred to as “the start of Russia’s invasion” or “the start of the war in Ukraine.” Chapeye’s vivid descriptions of the chaos and casualties of 2014, and of the men joining Russian-led militias but first making “business trips” to Moscow, serve as an important reminder to a foreign audience that Ukrainians were already long familiar with Russian destruction.

Chapeye noticed Russia’s impact not just on Ukraine, but on how Ukrainians relate to each other. Earlier in the book, he seems to be able to find a common language to relate to his countrymen, whether speaking to someone near the Russian border or in the Carpathians, despite regional stereotyping.

After 2014, Chapeye realizes that he can no longer speak to his fellow countrymen in the east without hearing ambiguous language fuelled by Russian propaganda. As Russian disinformation pollutes any sense of truth, he notices that euphemisms and vague descriptions like “our guys,” “those guys,” or “let’s-call-them terrorists” seep into everyday conversation with locals in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

Semantics become laced with tension and conversations take twists that neither Chapeye, nor the reader, could expect. An older man in Donetsk Oblast, Tykhon Borysovych, tells Chapeye that in his opinion, during World War II, at least “things made sense.”

Chapeye expects the man to talk about the fight against Fascism and the clear battle against evil. Instead, the man argues that the literal manner of fighting does not make sense, as “back then they would bomb, and then the infantry would launch an offensive. Everything was clear.”

In this war, he complains, one side bombs, and then the other side bombs, Tykhon Borysovych tells him. “What was the bombing for then?” He poses another rhetorical question that leaves Chapeye disturbed. “What kind of war is this,” he asks, when “only” four people in the neighborhood have been killed?

Another story is set in a shelter in Kharkiv for internally displaced people from Donetsk and Luhansk. Chapeye hears the story of Liuda, a young mother of three children, one of whom has Down syndrome.

She talks about their harrowing journey out of Russian-occupied territory, about how her husband can’t find a job as “no one’s hiring the ‘Donetsk types’,” and about their family members left behind.

Chapeye suddenly breaks the third wall and for the first time, after 200 pages, appears to address the reader directly. “Don’t start feeling sorry for them. Don’t start personally living through other people’s stories,” he says, as if repeating a mantra that an aid worker has told him.

“There are a million displaced persons. A million is just a number. Each of them individually is a person. But a million is just a number. The important thing is to perceive them as numbers, not as people. It’s easier like that,” Chapeye writes as if continuing to cite an aid worker he encountered at the shelter.

Chapeye’s preface to the English edition is titled “A Million Stories.” He describes how his own family fled Ukraine in February 2022, how he joined the army, and how increasingly terrible things started “happening to people increasingly close to me.” He notices how the men serving in the unit with him, each with their own complexities, hopes, and dreams, could be “unwritten stories from the book.”

As Chapeye’s first book published in English, “The Ukraine” is notably far from an optimistic account of a united nation. What the book does do, however, is rally against viewing Ukrainians as simply numbers, fleeting headlines, or statistics on a screen – something that is needed more than ever. “The Ukraine” reminds the reader that behind every Ukrainian is a story.