As Russia recruits Ukrainian teens for sabotage, Ukraine races to reach them first

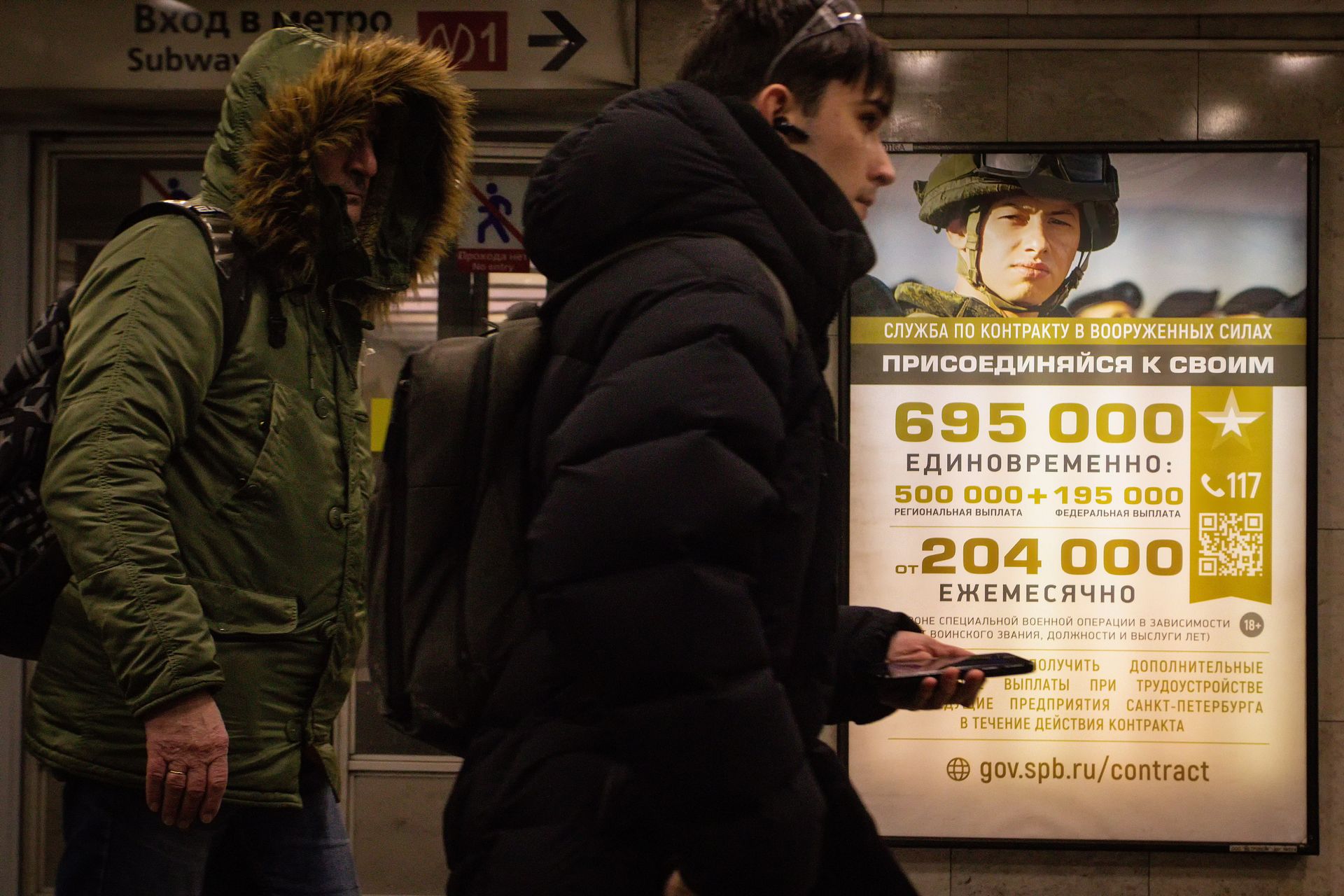

A photo released of two teenagers aged 15 and 17 who sought quick money on Telegram channels, but were unwittingly used as Russian suicide bombers in Ivano-Frankivsk, the Security Service of Ukraine said. (Security Service of Ukraine)

As Ukraine’s teenagers get ready for a new school year in a country at war, they face yet another threat — a network of Russian operatives trying to trick them into betraying their country.

For the past year, Ukrainian headlines have tracked a series of shocking incidents where young people recruited by Russian state actors on messenger apps — particularly Telegram — have planted bombs, lit vehicles on fire, painted anti-state graffiti, and shared photos of potential military targets with Russian operatives.

The recruitment scheme that Russia has developed is large, with careful planning, said Vasyl Bohdan, the head of the Juvenile Prevention Department of Ukraine's National Police. "For the most part, the children don’t understand what is happening, or that it’s very serious."

In some cases, the teens believe they are playing a game or delivering innocuous packages. In others, after they’ve realized what’s happening, they’ve been blackmailed with compromising photos or threats to expose them as collaborators by their Russian handlers.

Of more than 700 individuals that the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) has arrested in the past year and a half for similar espionage and sabotage acts, around a quarter have been carried out by Ukrainian youth under the age of 18, the SBU told the Financial Times in June.

"For the most part, the children don't understand what is happening."

The cases that stick in Bohdan’s mind the most are the ones where the youth have been used as unwitting suicide bombers. In March, Russia's intelligence services remotely detonated an explosive device it had paid two teenage boys in Ivano-Frankivsk to plant, killing one of them and injuring the other.

The techniques used by Russian intelligence are age-old spycraft tools of manipulation and control, updated for the digital era. But the ubiquity of technology has made teenagers — whose lack of world experience makes them particularly susceptible to these techniques — easier than ever to reach at scale.

Ukrainian authorities have taken note, rolling out a series of campaigns specifically aimed at educating and protecting young people.

So far, they're working, Bohdan says, pointing to decreasing cases of teenage sabotage and growing reports of foiled recruitment attempts. But, he adds, the urgency hasn't let up, as Russia continues its attempts.

The app at the root of these cases

Ukrainian authorities have seen cases of teens being recruited in city centers and rural villages, in front-line eastern regions, and in the far west, away from the battlefield. But nearly all the cases have one thing in common — the teens were contacted by Russian agents on Telegram, the globally popular Russian messaging platform with over 1 billion users worldwide.

"You can find almost any type of criminal activity on Telegram," said Eric Clay, director of marketing for the Montreal-based security firm Flare. From illegal drugs and weapons for sale, to bank fraud and sextortion schemes, "Telegram is one of the primary methods cyber criminals use to communicate."

For criminals around the world, the platform is perceived as being more anonymous and less willing to cooperate with law enforcement to stop illegal activity.

For Russia, the platform is a highly useful tool for influence campaigns and propaganda, especially in Ukraine.

"Why is it used? It's used mainly because it's very popular in Ukraine," said Clay. "Another point is that you have very big groups. You can have up to 200,000 people in one group, so you can easily have huge audiences."

According to a survey last year by the Center for Insights in Survey Research, 86% of Ukrainians between the ages of 16 and 35 said they use Telegram on a daily basis — significantly higher than any other social media platform surveyed. Less than 5% said they had never used it.

Because of its use as a vector for Russian influence, Ukraine has faced calls to ban or restrict the use of Telegram, though these have failed to dent its popularity.

Even Ukraine's top government officials use Telegram as a key way to communicate with their citizens, including sharing critical wartime updates.

"There is (currently) no legislation that would allow Ukraine to effectively combat risks and threats on Telegram," Mykola Kniazhytskyi, a lawmaker from the European Solidarity Party, told the Kyiv Independent. "As far as is publicly known, Ukrainian authorities currently send requests to Telegram headquarters, but do not receive answers."

Last year, Kniazhytskyi and others submitted a bill that would require additional transparency from messaging companies. The bill, which has failed to gain traction in parliament, would have allowed the government to restrict the use of messaging platforms that refused to share information about their ownership or funding structure, including Telegram.

"Telegram’s main advantage (for bad actors) over other platforms is that it does not respond to either Ukrainian or European competent authorities. That is why a large space opens up for disinformation using Telegram," Kniazhytsyi said.

A psychological issue more than a technical one

Telegram channels dedicated to job-seekers are one common place that teens are found on the app, said Bohdan, since they're already looking for work, but other channels are used as well. From there, persuasion typically occurs in three phases.

"Initially, recruiters act gradually," Bohdan said. "First, they establish contact, demonstrate friendship, support, and communication, to overcome the psychological barrier of unfamiliarity."

The next step might be a low-stakes request like photographing a building, mailing postcards, or scrawling graffiti, he said. "For children, they feel that it is not difficult and the money is good."

"And so it happens that the poor guy didn't realize he was sucked in."

From there, though, the requests typically escalate. They might be asked to set military vehicles or sensitive buildings on fire, or to purchase explosive components or deliver packages.

"Younger people are much more easily triggered. They haven't learned how to self-regulate."

At that point, teenagers who hesitate have been blackmailed by their previous acts into further compliance.

Part of the reason teenagers are more easily recruited is simple biology, said Anna Collard, an expert in cyberpsychology and how human behavior affects security for the cybersecurity firm KnowBe4 Africa.

Most scams and attacks happen not because of a technological error, but when emotional vulnerabilities are exploited, she added.

"Younger people are much more easily triggered. They haven't learned how to self-regulate. And so a lot of the emotional techniques — the cognitive biases that are being triggered on purpose (in scams or recruitment) — work so much better on these younger people because of their cognitive susceptibility," Collard said.

"Ultimately, from a defense point of view, it's a societal and psychological human issue, much more so than a technical one."

An effective campaign

One of the key messages that Bohdan's team has tried to instill through their youth campaigns is what to watch out for — and emphasizing that there's no such thing as easy money. Another key message they try to convey is that it is never too late to go to the police.

"Even if they try to put you on the hook for blackmail," he said, "contact the police, contact law enforcement agencies, contact security services. It's already a mitigating circumstance. The main thing is that you turned (to the authorities), that you warned of further potential tragic consequences."

Speaking directly to children in classrooms, at summer camps, and online, Ukrainian officials share warning signs and what to watch out for, as well as ways to report suspected recruitment attempts. The campaign involves not just the juvenile prevention police officers, but also partnering with parents, teachers, digital security NGOs, and other Ukrainian divisions, including local territorial authorities, and the ministries of education and social policy.

Even celebrities have been enlisted to help. Ukraine's heavyweight boxing champion, Oleksandr Usyk, was brought in to speak to a group of students attending online lessons, in the hopes that children would listen to him more closely and spread his advice to friends.

Additionally, cyber police and cyber units of security services monitor information flows online and spread information about Russian threats. A new Telegram chatbot operated by Ukraine's security services makes it convenient for Ukrainians to report attempted recruitment.

All these efforts have borne fruit: the number of successful child recruitment cases has decreased "exponentially" over the past year, said Bohdan, proportional to the number of failed attempts that the country's youth are bringing to the police's attention. Already, there are 74 cases where young people have notified the police about ongoing recruitment efforts.

"Children are realizing that this is not just an offer for work, or casual communication, or a request. They understand that this is an illegal activity of the enemy in order to destabilize our country," he said. "And they are appealing to the police."