Kurkov’s new historical detective novel is full of thrills, light on the history

Like any true detective novel, Andrey Kurkov’s “The Silver Bone” starts off with a brutal murder and endeavors to maintain high stakes until its final pages.

The novel, now available to English-language readers in translation by Boris Dralyuk, was recently longlisted for the International Booker Prize, one of the most prestigious awards for translated literature. It is the second year in a row that one of Kurkov’s books earned the nomination.

Samson Kolechko, the main character of “The Silver Bone,” is a budding engineer who suddenly finds himself working as an investigator on Kyiv's new police force in the Bolshevik-controlled city. A series of events, starting with the murder of Kolechko’s father and the loss of Samson’s ear in the very same attack, followed by the imposed lodging of two dubious Red Army soldiers in his family home, eventually lead to this career change. Soon enough, he starts investigating a double murder.

“I’ll be fighting to restore order,” Kolechko explains his choice to the doctor who helped treat his wound. At the same time, Kolechko also denies becoming a supporter of the revolutionary cause. Before they part ways, the doctor cautions him that order “comes in many varieties these days,” underscoring the instability of life in Kyiv.

“None of these (interpretations of order are) written down on paper, and they all change like the weather in England. Nothing is settled. Yet that’s precisely what life requires — a settled order, established by law, so that the same rules apply to everyone.”

Kyiv of 1919 is depicted in “The Silver Bone” as a place where the threat of death lurks around every corner. At night, so-called bandits – this term seems to apply throughout the novel, not just to petty thieves – and Red Army soldiers alike roam the streets. As Kolechko notes, the nighttime atmosphere of Kyiv “amazed and frightened” him “to no end.”

During this period, Red Army soldiers requisition all sorts of items ranging from underwear to furniture from locals, sometimes resorting to brutal force. It is later revealed that requisitioned items must be taken to warehouses, counted, and accounted for. However, some soldiers opt to keep these items for themselves for a number of reasons, mostly for personal gain. Soldiers also carry official documents mandating that they be provided lodging in homes.

In an element of magical realism that sets the story apart from a more straightforward mystery thriller, Kolechko retains the ability to hear through his severed ear. Kept first in a drawer in his father’s desk at home and later at the local police office where he works, the ear picks up nearby conversations. This helps Kolechko gain a heads up of any imminent danger, such as when the two Red Army soldiers billeted in his home, Anton and Fyodor, quietly debate at night whether to kill him or not.

Other narrative aspects veer toward mundanity, like Kolechko’s love interest. Described as "a girl of excessively athletic appearance" employed at the Provincial Bureau of Statistics, Nadezhda is introduced to the reader as a potential wife for Kolechko by his elderly neighbor.

Nadezhda maintains a consistent presence throughout the novel, but her character growth is limited. It seems that her main role is to support and reaffirm Kolechko’s every step along the way of the story. Even her name – which translates to “Hope” – implies a certain feminine docility for him to cling to. At the same time, she appears to believe in the Bolshevik’s efforts to solidify control, making sweeping declarations like "Without strong leadership, people become feral" and "Work shouldn’t be interesting. It should be important and necessary for society.”

While the Bolsheviks control Kyiv at the novel's outset, their grip on power is far from secure, with opposing forces encircling the city. These include not only various Ukrainian factions but also the White Army intent on restoring the Russian Empire.

However, the novel fails to properly introduce any competing groups vying for control of Kyiv besides the Bolsheviks, resigning them to proverbial boogeymen. The majority of Kyivans, meanwhile, are portrayed as weary onlookers trapped in the turmoil of ongoing regime change, with their primary focus being survival above all else.

A selected chronology of Ukrainian history is given at the novel’s end to better understand the time period in which the novel is set. But for those already knowledgeable about the history, it feels like a hasty afterthought and leaves the reader with a sense of being shortchanged.

The years from 1917 to 1921 were a critical point in Ukraine's modern history. Following the fall of the Russian Empire in 1917 and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, Ukraine was poised to form its own independent state. One of the main challenges was that different factions held varying views on who should rule and how.

The Bolsheviks were also resolute in maintaining Russian control over Ukraine. In 1919, as the novel’s events unfold, the Soviets control Kyiv. However, the end of the Ukrainian-Soviet War, which resulted in a total Bolshevik victory and the establishment of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic as part of the larger Soviet Union, would not come until later in 1921.

The rule of the Bolsheviks over Kyiv, as well as the rest of Ukraine, would come to be largely defined by political repression and murder. However, the scale of this looming tragedy is not yet clear in Kolechko's adventures. The reader's primary emotional connection lies with the new police force that Kolechko is a part of, which continually emphasizes the need for order and implementing plans for a new future.

Repeated references are also made throughout “The Silver Bone” to the Cheka, who, for the casual reader unfamiliar with Soviet history, might seem like law enforcement officers who operate with a higher level of authority than Kolechko and his colleagues. The reality is far more sinister. The Cheka was the first iteration of the Soviet secret police. The organization’s mission was to suppress so-called counterrevolutionary activities, and its agents would go on to become symbols of authoritarian terror for the thousands of people they killed.

Ukrainian military leader and politician Symon Petliura, who played a crucial role in the fight for Ukraine’s independence during this period, exists on the novel’s periphery. The murder of Kolechko’s father and the loss of Kolechko’s ear at the beginning of the novel are attributed to Petliura’s Cossacks, who are accused of "cutting people to pieces, right out on the street — for nothing," and Nadezhda’s father goes so far as to label Petliura’s men as "evil."

Some argue that Petliura could have done more than he did to prevent pogroms carried out by soldiers under his command, but he is widely regarded as a national hero in Ukraine today for his role in the fight for Ukrainian independence. Petliura also did a lot to promote Ukrainian culture on both a national and international level.

He was assassinated in Paris in 1926, and many believe his death to have been orchestrated by the Soviets. After his death, the Soviets attempted to discredit him, as they did with many Ukrainian cultural figures, spreading the notion that Petliura was little more than an anti-Semite and a rioter.

Anton Denikin, the Russian military leader of the White Army, is treated with slightly more ambiguity in the characters’ conversations about the ongoing situation than Petliura. “(Denikin’s army) will come to Kyiv — are they good? Evil?” wonders Nadezhda’s father.

Kolechko also muses while looking at currency that had lost its value to vouchers or the exchange of material goods under Bolshevik rule how “Denikin was a tsarist through and through — if he should win, he’d certainly restore this double-headed eagle money (of the Russian Empire).”

Denikin was an ardent believer in the imperial Russian project, meaning that for him, an independent Ukraine just didn’t exist. He, like many Russian imperialists, referred to Ukraine as a “little Russia.” Under his command, the White Army carried out a number of war crimes that later came to be known as the White Terror.

One might argue that Kurkov, as a novelist, isn't obligated to delve into these historical details. However, it's worth questioning why the novel's protagonist, a young Ukrainian man seeking solace amid the political and military upheavals around him, chooses to do so by aligning with the Bolshevik project.

Kolechko, while not one to spout revolutionary slogans, gradually adapts to the authority bestowed by his new status. One evening, as he walks Nadezhda home, she asks him to fire a shot into the darkness with his revolver “so that instead of us being afraid, people will fear us.” Eager to impress her, he does it.

Is Kolechko meant to be viewed as a hero for the reader to sympathize with or a budding anti-hero to be wary of? Kurkov's “The Silver Bone” is the first in a series, so the character’s ultimate trajectory will become clear. But the ending of the first novel, marked by romantic triumph and the promise of more adventures, leaves a bitter aftertaste for those who know what comes next in the dark history of Soviet-controlled Ukraine.

Note from the author:

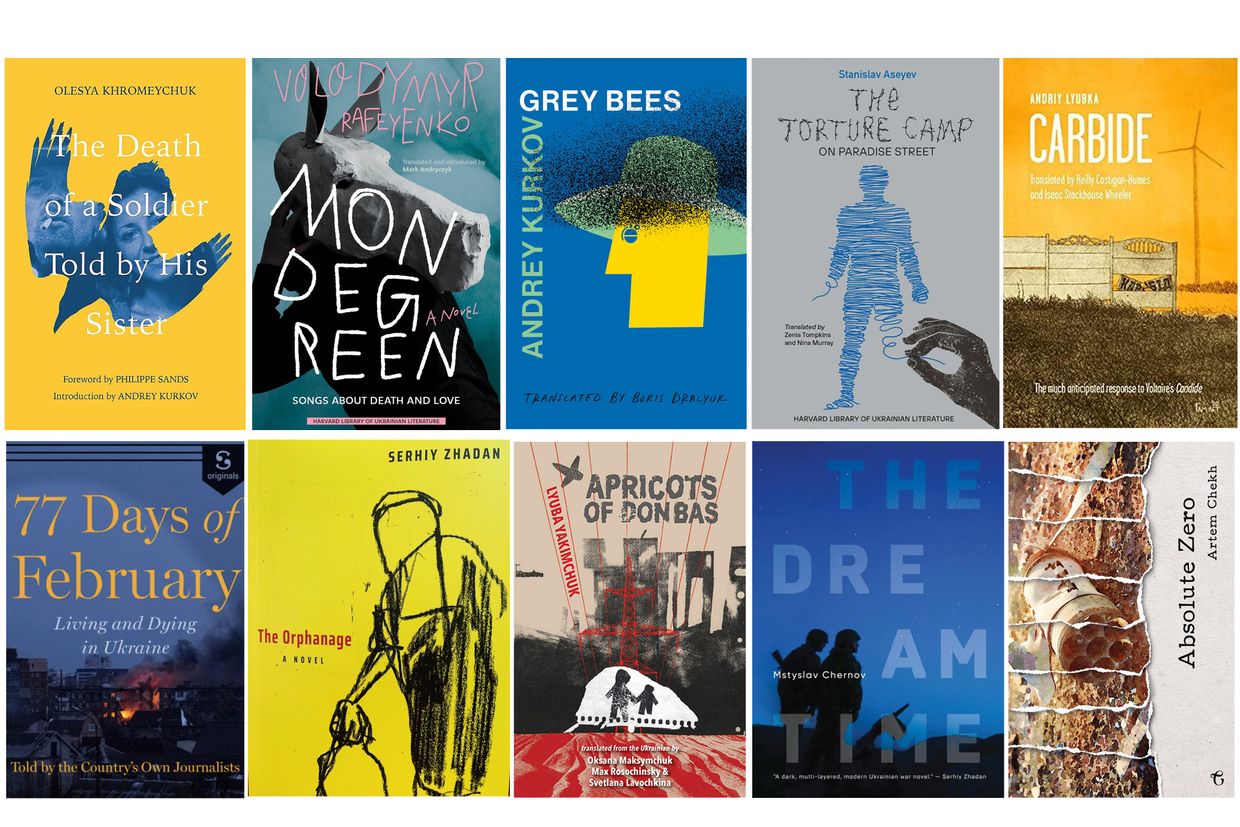

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, thanks for reading this article. There is an ever-increasing amount of books about Ukraine available to English-language readers, and I hope my recommendations prove useful when it comes to your next trip to the bookstore. Ukrainian culture has taken on an even more important meaning during wartime, so if you like reading about this sort of thing, please consider supporting The Kyiv Independent.