What English translations miss about Bulgakov — and why it matters in Ukraine

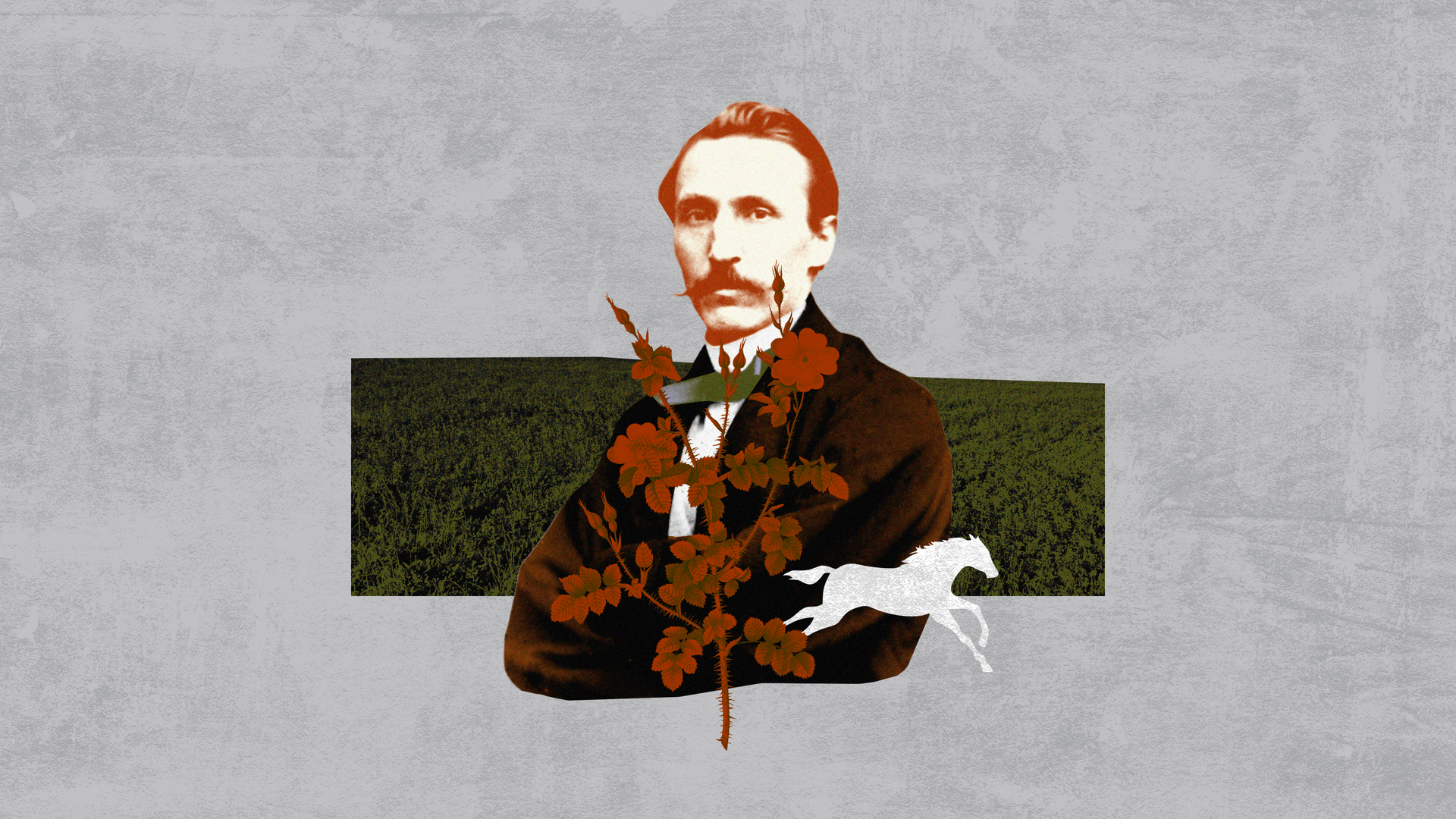

Twentieth-century author Mikhail Bulgakov is seen in 1928. (Wikimedia)

Twentieth-century author Mikhail Bulgakov is celebrated worldwide for his satirical genius and his defiance of Soviet power, most famously through works like "The Master and Margarita" and "White Guard."

In Ukraine, his legacy is far more complicated.

Rather than being remembered solely as a critic of totalitarianism, Bulgakov is seen by many as a symbol of Russian imperial culture for his hostility toward Ukrainian cultural identity.

Born in Kyiv in 1891, Bulgakov grew up speaking Russian and studied medicine at Kyiv University. His upbringing in the city coincided with a period of intense national awakening in Ukraine, but Bulgakov himself expressed disdain for Ukrainian culture and language.

In his 1925 novel "White Guard," the protagonist rails against Ukrainian leader Pavlo Skoropadskyi during the Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-1921), declaring, "I'd hang your Hetman myself for the way he has set up this cute little Ukraine… Who terrorized the Russian population with that vile language that doesn't even exist in the world?"

Such sentiments, repeated in his personal letters and essays over the years, illustrate a broader pattern: Bulgakov largely aligned himself culturally with Russia while rejecting the legitimacy of Ukrainian national aspirations.

This legacy has sparked controversy in contemporary Ukraine. In mid-December 2025, a monument to Bulgakov in Kyiv was dismantled as part of a broader effort to reassess public symbols tied to Russian culture and influence. This process was accelerated by the war that began in 2014 and intensified after Russia's full-scale invasion in 2022.

"Right now, authors like Bulgakov are part of the discourse of the so-called Russian world, and engaging in serious debate about them is premature."

Bulgakov's former Kyiv home, long maintained as a museum, also faces an uncertain future amid debate over whether a writer who rejected Ukrainian independence should be publicly honored.

This scrutiny of Bulgakov's place in contemporary Ukraine underscores that, for many Ukrainians, an author's literary merit alone cannot detach certain writers from the enduring realities of Russia's full-scale war.

"Purely literary discussions (about the merit of Bulgakov's work) can only be revisited after some time, following the complete collapse of Russia," literary scholar Rostyslav Semkiv told the Kyiv Independent.

"Right now, authors like Bulgakov are part of the discourse of the so-called Russian world, and engaging in serious debate about them is premature," Semkiv added, emphasizing that any attempt to challenge this narrative could risk retraumatizing Ukrainians who have lost their relatives, homes, and hopes for a peaceful life.

As the full-scale war drags into its fourth year and evidence of more atrocities in Ukraine continues to emerge, some well-known Russian authors even say they understand, and support Ukrainians’ efforts to reclaim their cultural landscape, including moves to push aside canonical figures like Bulgakov.

“Let the Ukrainians live as they want to, read whatever authors they want to read — what really matters is that my Russian compatriots stop tormenting and killing them,” Russian novelist Boris Akunin wrote on social media shortly after the Bulgakov monument was dismantled in December.

The Ukrainophobic elements of Bulgakov's work can be difficult for some foreign readers to grasp, given that some examples are either absent from the English translations of books like "White Guard" or watered down.

Sign up for our newsletter

For instance, a 2008 translation published by Yale University Press renders the protagonist's rant about "this cute little Ukraine" — a phrase intended to convey contempt — as "this dear Ukraine of ours!"

An earlier translation, published in 1971 by McGraw-Hill, omits the remarks about Ukraine in that specific rant altogether and compounds the problem a few pages later by mistranslating a joke that hinges on a linguistic slight: the Ukrainian word "kit," for cat, mocked by a character in contrast to its Russian homonym meaning whale.

As for the 1971 edition, it is unclear whether the translator had access to the original version of the novel or one that had passed through Soviet censorship boards.

Bulgakov is not the only author whose legacy is under scrutiny in Ukraine. In mid-December, the Kyiv city council also voted to take down a monument honoring the poet Anna Akhmatova.

Born in Odesa, Akhmatova became known for poetry marked by moral courage under Soviet repression. Still, despite knowing Ukrainian and even translating Ivan Franko from Ukrainian into Russian, she never considered herself a Ukrainian writer.

In the 1939 work "Notes on Anna Akhmatova" by the poet Lidiya Chukovskaya, Akhmatova is quoted reflecting critically on her time in Ukraine, saying she "never came to love that country or its language."

Journalist and editor Vitaliy Portnikov weighed in on the debate over the significance of these authors, noting that advocating for the removal of monuments to figures like Bulgakov or Akhmatova in Ukraine doesn't prevent people from reading these authors.

"I resolutely do not understand why Ukraine should (publicly) honor with memorials people who chose Russian culture for their creative self-realization, while treating with contempt or indifference the civilization of the country where they were born," Portnikov wrote.

"Will Bulgakov or Akhmatova be read in a Ukraine that has successfully fought back? Over time, yes — but in Ukrainian translation and with an awareness of context. But monuments to figures of Russian culture will no longer appear in Ukraine — and every sane person understands perfectly well why."