Ukraine's embattled steel sector's latest struggle? Polish protectionists

An employee works in an open-hearth furnace shop at Zaporizhstal in Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine, on Nov. 13, 2024. (Ukrinform / NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Ukraine’s metal sector says it is being made a scapegoat for Poland's steel troubles, as Polish groups urge Warsaw to press Brussels to limit growing Ukrainian imports.

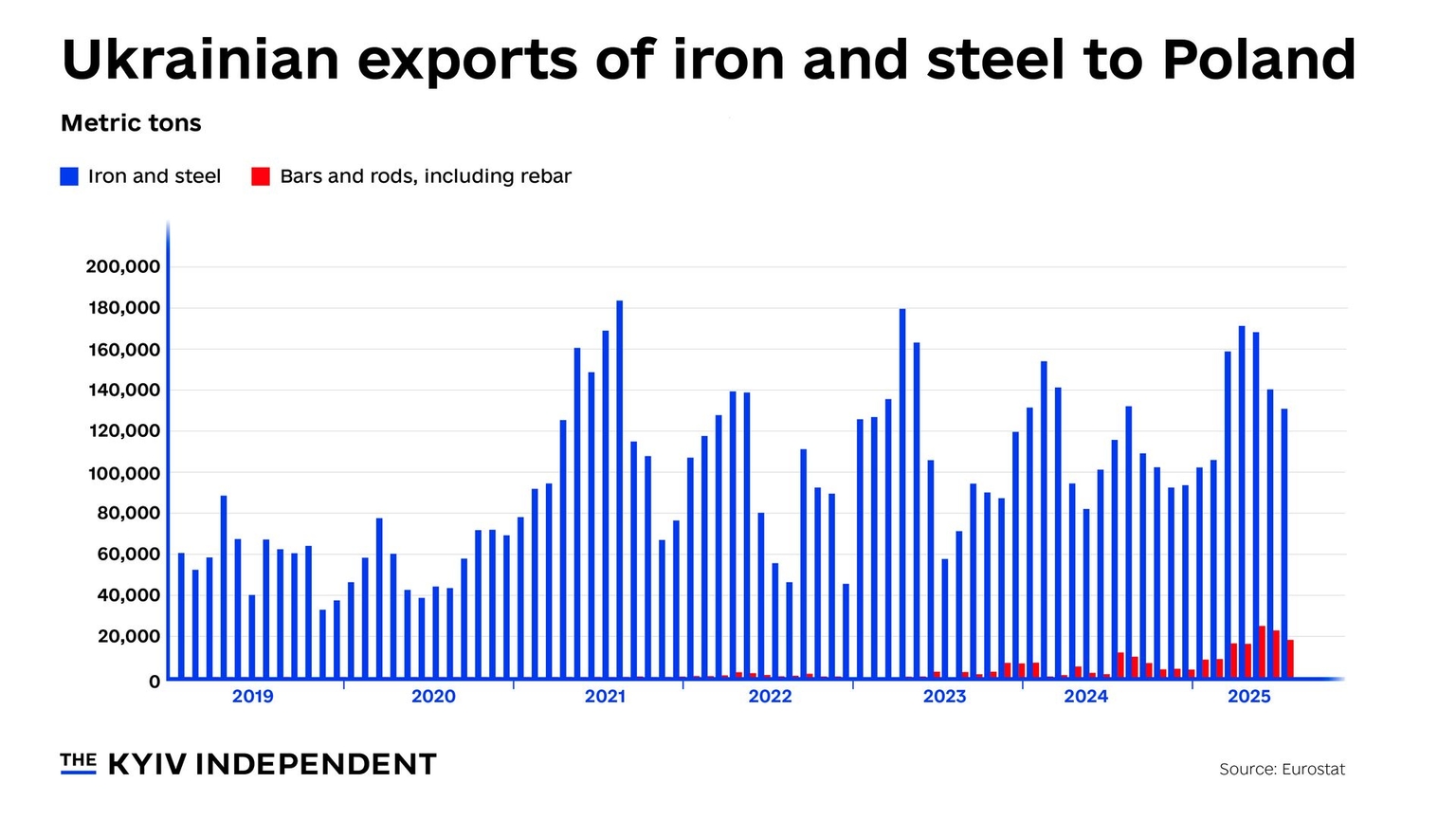

In the first half of 2025, Ukraine's steel exports to Poland slightly increased. In response, Polish industry associations and trade unions are now complaining about unfair competition and demanding a 12-month embargo on Ukrainian steel.

Ukrainian producers point out that export levels remain below pre-full-scale invasion 2021 figures. They also note that Ukraine's war-battered steel industry doesn’t have the capacity to compete with Poland’s growing steel production.

If Warsaw introduces additional restrictions, it could raise costs for Ukrainian producers and even halt domestic steel production, Oleksandr Kalenkov, president of Ukrmetalurgprom, a Ukrainian steel makers association, told the Kyiv Independent.

"Poland is trying to find somebody to blame" for its uncompetitiveness on the steel market, Kalenkov said.

"(Polish producers) have problems competing because of higher electricity prices than other EU countries, and uncompetitive prices from other European companies that are still buying cheap Russian slabs and Russian semi-finished products," Kalenkov said.

"Our companies are trying to survive and not even profit, but at least decrease their losses."

The European Union suspended restrictions on Ukrainian steel imports in June 2022 after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion. But the EU is currently crafting a new regime that could limit imports of Ukrainian steel, set to be introduced in mid-2026.

Ukraine’s metallurgy sector has been one of the hardest hit by Russian aggression. Steel production plummeted from 22 million metric tons in 2021 to just 7.6 million metric tons last year.

Metinvest, owned by Ukraine’s richest man and once a national giant, lost 65% of its business after Russia occupied and destroyed its two largest plants — Azovstal and Illich in the now-occupied city of Mariupol.

If Ukrainian manufacturers are forced to further drop production, it would eat into Ukraine’s state budget — the top four metallurgy companies paid $780.4 million in taxes last year — meaning less money for defense. Without steel production, Ukraine would be more vulnerable on the battlefield and need further EU financing to sustain its army, said Kalenkov.

Are Polish claims well-founded?

Recent reports in Polish and international media describe a surge in Ukrainian steel imports, putting pressure on Polish mills and causing the industry to seek protective measures.

A principal complaint is a rise in imports of reinforcement bars that Polish mills specialize in. One of the reasons companies are exporting more to Poland is that they want to cut expensive logistics costs by exporting to the closest country, said Kalenkov.

Ukrainian overall steel exports to Poland in the first seven months of 2025 were about 19% higher than the same period in 2024, according to Eurostat, but by no means unprecedented in recent years.

While Ukrainian exports of reinforcement bars to Poland have increased to unprecedented levels in 2025, they constitute a fraction of overall exports of iron and steel to Poland.

Poland’s steel industry argues that Ukraine is not subject to the same energy or environmental costs. While Poland does face some of the highest electricity prices in Europe, averaging 89.6 euros per megawatt-hour in August, it's dwarfed by Ukraine’s costs — 115 euros/MWh.

Gas and coal costs have also been consistently higher for Ukrainian producers than Polish companies over the last few months, ArcelorMittal Kryvyi Rih’s press service told the Kyiv Independent. The Luxembourg-headquartered steel titan has five plants in Poland, accounting for over 50% of the Polish market.

"How can the devastated Ukrainian steel industry, which is struggling to survive the war, pose a threat to the Polish steel industry?" Stanislav Zinchenko, chief executive of consultancy GMK Center, told the Kyiv Independent.

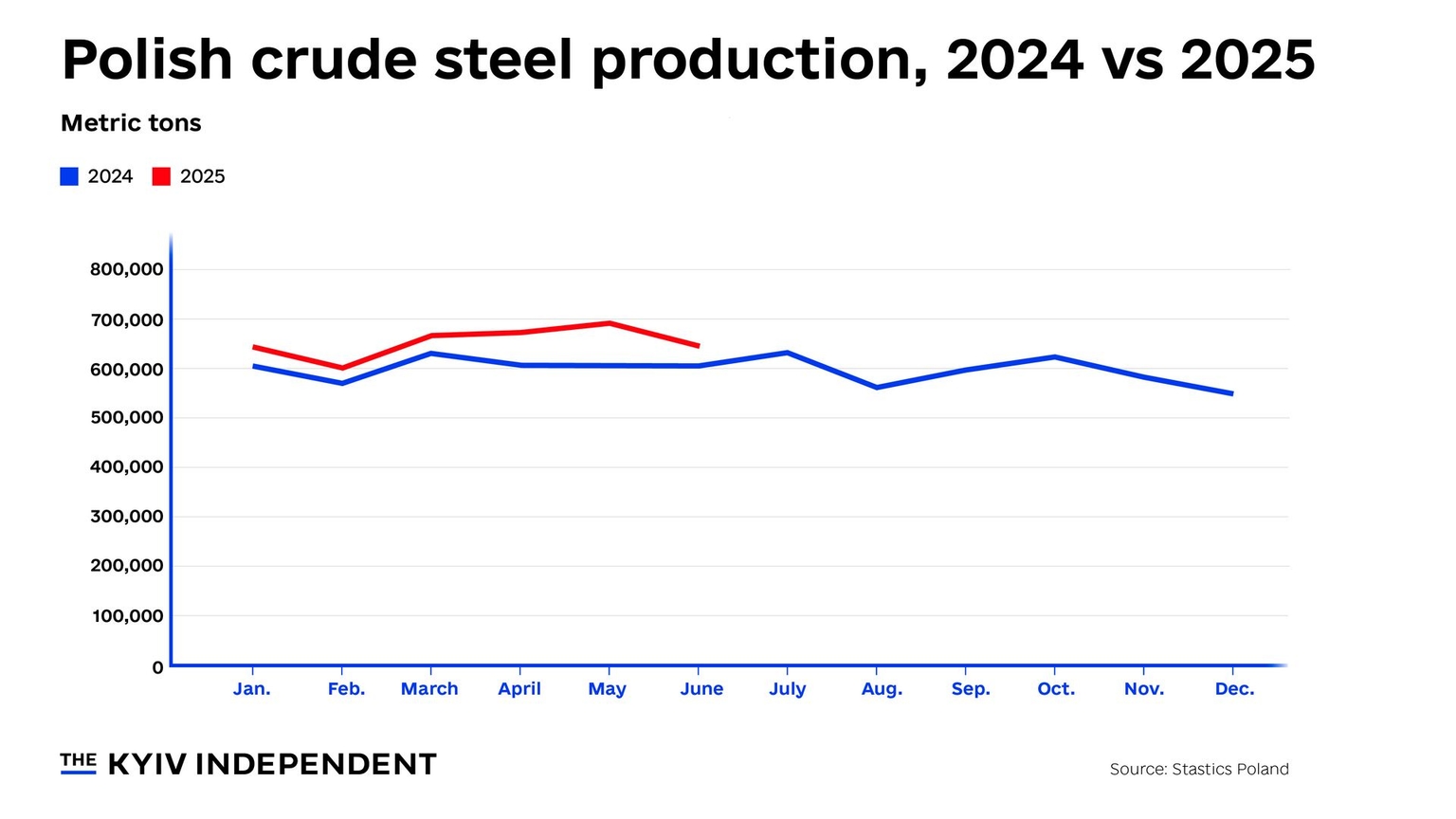

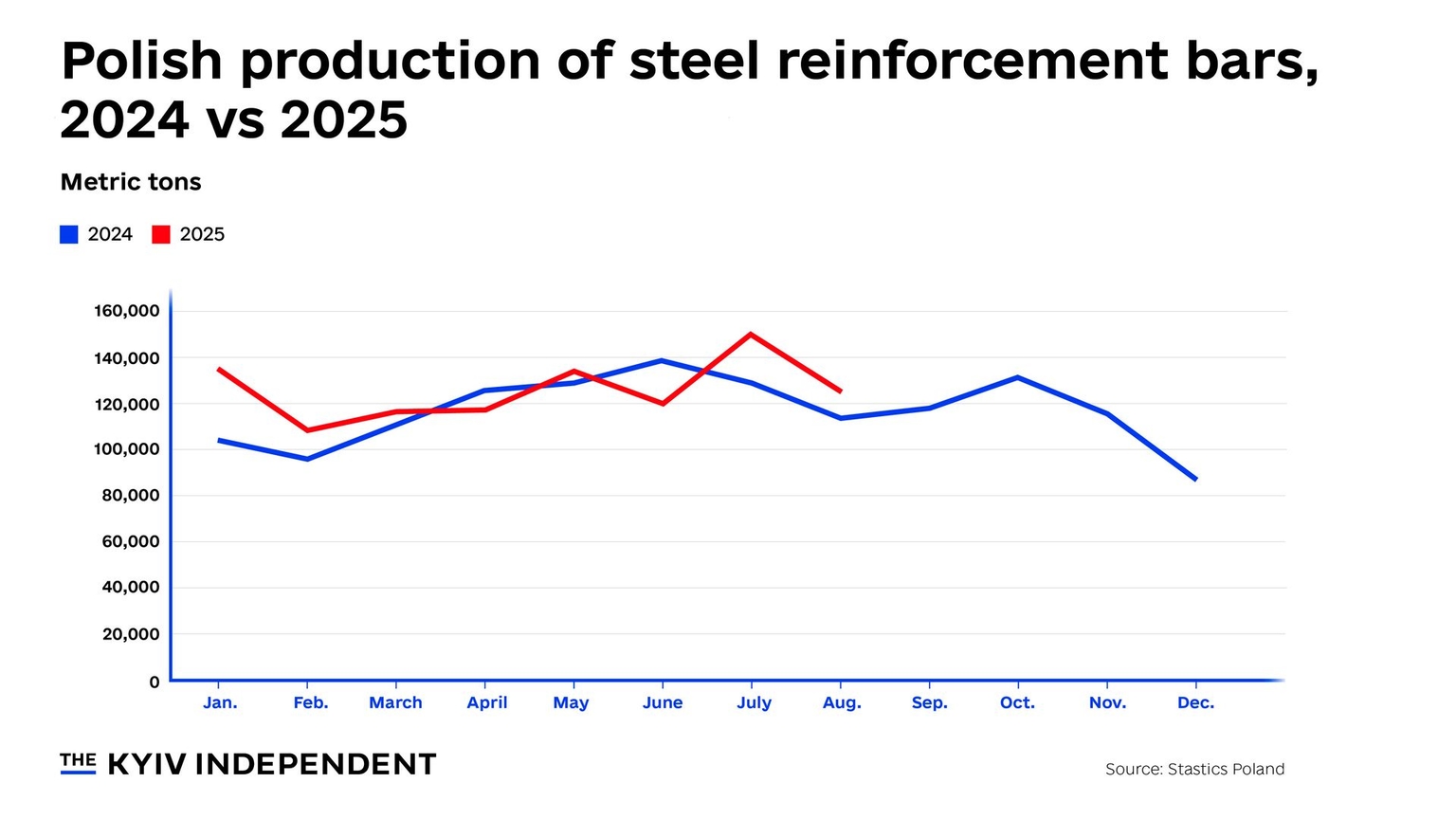

"Poland’s steel industry does not have problems. It has growth,” he added.

Overall crude steel production was up 8% in the first six months of 2025 compared to the same period last year, according to Poland’s statistical office. Domestic output of reinforcement bars in the first eight months of 2025 was just over 1 million metric tons, up 6.4% from the same period in 2024.

"In our view, limiting or banning Ukrainian imports will not solve internal problems or increase efficiency of the Polish steel industry," ArcelorMittal Kryvi Rih said in a written statement to the Kyiv Independent, adding that the complaints were "political" rather than "factual."

"Ukrainian companies that comply with all EU norms in exporting to the EU should not be a scapegoat for politicians," the company added.

Repeating trade tensions

This is not the first time Poland has complained about Ukrainian exports. Polish farmers staged mass protests in 2023 and 2024 against the influx of Ukrainian grain, even blocking border crossings.

Industry groups similarly argued that Ukrainian imports were undermining domestic producers. Poland, along with Hungary and Slovakia, introduced a unilateral ban on certain Ukrainian food products in September 2023.

For now, Brussels has not commented on the calls from Poland’s steel sector.

Europe imports about 30 to 35 million tons of steel, while Ukraine’s exports were about 2.2 or 2.1 million, according to Zinchenko. "Our two million is nothing on the European market," he said.

In Poland, Germany is the most important international partner when it comes to steel — 27% of Poland’s steel imports came from Germany in the first eight months of 2025, compared to just 14.7% from Ukraine, according to Eurostat.

With exorbitant costs, Ukraine is struggling to compete on the EU market, particularly as producers from other EU states like Czechia use cheap materials from Russia, said Kalenkov.

"It is much more important to limit trade with Russia, not with Ukraine," Dmytro Kysylevsky, a Ukrainian MP and coordinator of the Made in Ukraine policy, told the Kyiv Independent.

Knock-on effects

Restrictions on Ukrainian steel exports would be a blow to the already struggling industry. Mounting Russian attacks on Ukrainian energy facilities are causing steelmakers to scramble for expensive generators and alternate electricity between different sections of their plants. A dwindling workforce also means Ukraine’s steel companies have reached full capacity.

Limitations on Ukrainian steel producers would also drag down one of the country’s largest employers — the state-owned Ukrainian Railways, which generated $500 million in profits from freight traffic last year. Metallurgical products make up 16% of Ukraine’s exports, with the largest steel company, ArcelorMittal Kryvi Rih, generating around 5% of the freight traffic in Ukraine.

Polish companies would suffer too. Polish rail would lose revenue from transporting Ukrainian steel, while Polish miners would lose a major market for coke and coking coal — imports from Ukraine increased after losing the Pokrovsk mine earlier this year.

It’s an interdependent supply chain: Ukraine fuels its blast furnaces with Polish coke and coking coal to produce steel used by Polish processors, Metinvest’s press service told the Kyiv Independent. Excessive import restrictions would undermine Polish steel processors' competitiveness, it added.

"We have to do everything possible during the next weeks and months to make it clear to Poland, our European partners, and the European Commission that a working and growing steel sector in Ukraine would be beneficial for the European economy and for the Polish economy as well," said Kalenkov.