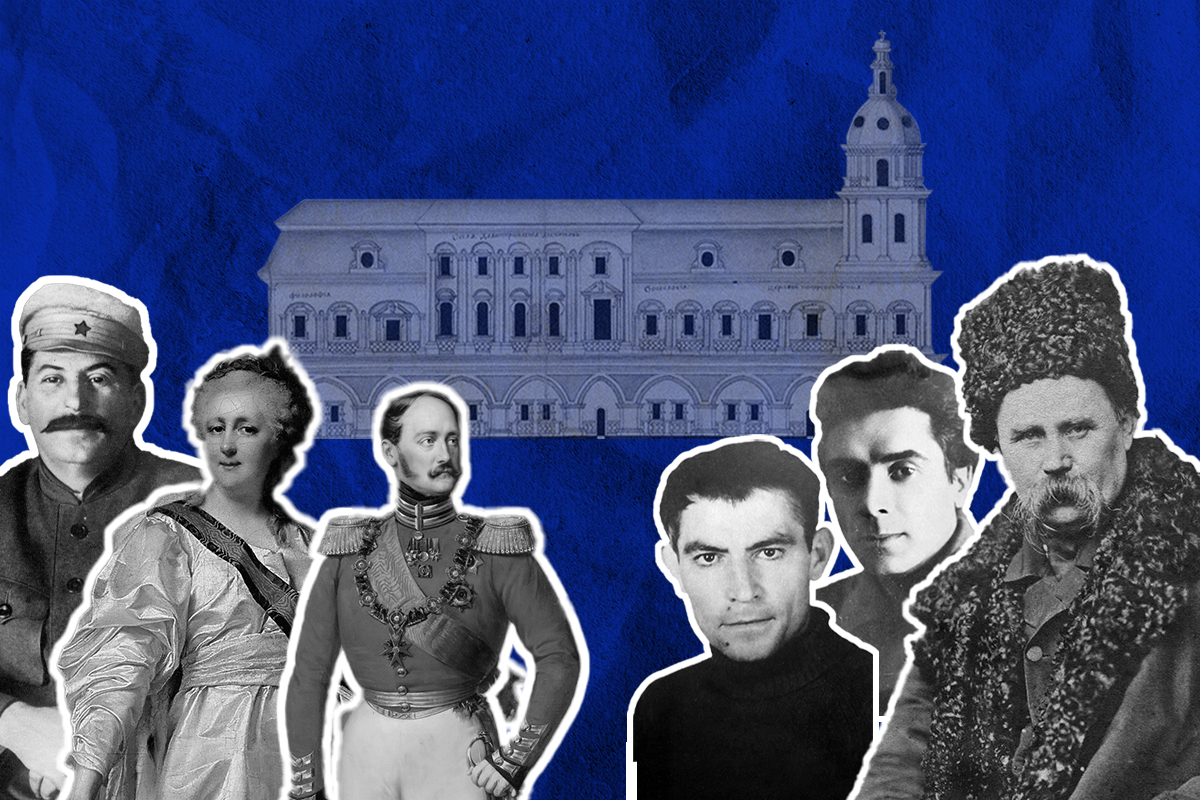

Russia’s war against Ukraine began not on Feb. 24, 2022, but in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea and the invasion of the eastern Donbas Oblasts. (Liza Yablonska-Mykhailus)

There is a reason why Ukrainians insist the world refers to Russia’s assault against Ukraine in 2022 as a “full-scale” invasion.

Russia’s war against Ukraine did not begin on Feb. 24, 2022, but in 2014, with both the annexation of Crimea and the invasion of Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region.

While the Kremlin openly boasted of its annexation of the Crimean peninsula, it tried to conceal its involvement in the war in Donbas for years.

Moscow instead spread the false narrative that self-organized “separatist” groups in eastern Ukraine were responsible for the aggression, despite no evidence to suggest that a genuine separatist movement existed in eastern Ukraine at the time.

Many politicians, experts, and journalists around the world have played into Russian propaganda, framing the war in Donbas as a civil war. Russian military formations were often referred to as Ukrainian “separatists,” despite the documented presence of Russian military personnel and weapons in Ukraine.

The West’s condemnation went as far as limited sanctions, which did little to stop Russia’s war. Ukraine was left alone to fight a war that killed thousands, plunged once-prosperous regions into chaos and poverty, and displaced over a million Ukrainians.

For the Kremlin, the incursion into Ukrainian territory was an attempt to impede Ukraine’s democratic, pro-Western course, and a precursor of the full-scale invasion in February 2022.

How did Russia invade and occupy parts of Donbas?

Just over a month before Russian military groups invaded Donbas in April 2014, the Ukrainian people successfully ousted Kremlin-backed president Viktor Yanukovych during the EuroMaidan Revolution.

The Kremlin capitalized on the post-revolutionary chaos and sent its troops into the Crimean peninsula days after the revolution succeeded in February 2014. They immediately took the peninsula under control, and proclaimed its annexation in March 2014.

Throughout March and April, demonstrations against the pro-Western revolution and in support of Russia began appearing in the east and south of Ukraine. Protestors demanded to hold local referendums on joining Russia – unconstitutional in Ukraine – among other pro-Russian demands. The demonstrations were small, numbering generally in the hundreds of people.

Ukrainian authorities have gathered evidence that these demonstrations were organized by Russian citizens who collaborated with Kremlin-linked politicians in Ukraine.

Sergey Glazyev, former advisor to Russian President Vladimir Putin, was tasked with organizing pro-Russian protests in Zaporizhzhia, Crimea, and Odesa, according to Ukrainian law enforcement findings in 2016. There were even reports of buses bringing crowds of Russian nationals to take part in the rallies.

Around the same time, armed men without insignia also managed to take over government buildings in the regional capitals of Donetsk and Luhansk, but didn’t immediately take full control of the two regional capitals.

The occupation of cities in Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts came in phases. While armed men infiltrated or took over government buildings in cities across the two oblasts in March and April, militants led by former Russian FSB officer Igor Girkin moved to formally occupy Sloviansk on April 12 immediately followed by Kramatorsk, cities north of Donetsk.

They were later kicked out by Ukrainian troops in July, moving to the regional capital of Donetsk, where they faced little resistance from the local or national forces.

In an interview to a Russian media outlet in 2014, Girkin openly claimed responsibility for helping to ignite the war in Donbas and confirmed the presence of the Russian military and weapons on Ukrainian territory. He has repeated these claims.

On May 11, 2014 militias coordinated by Russia proclaimed a sham referendum on the independence of what they refer to as the “Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics,” the name given to the Russian occupied, proxy-led parts of Ukraine’s Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts.

Russian proxies then announced around 90% support for independence in both oblasts. Ukraine and much of the international community have deemed these so-called referendums illegal and illegitimate.

How did Ukraine respond to the invasion?

In April, the Ukrainian government announced an “anti-terrorist operation,” often referred to in Ukraine as “ATO,” in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. The Ukrainian military and special forces then began engaging in armed clashes with Russian-led units in eastern Ukraine.

Ukraine was severely underprepared for the invasion. Decades of corruption had left the military nearly in ruins, while the government still wasn’t fully formed after Yanukovych was toppled in February.

Moreover, when the invasion started, Ukraine didn’t have a president. Parliament’s chairman Oleksandr Turchynov temporarily assumed the presidency after the revolution. Petro Poroshenko was elected president in late May, as battles in Donbas were already underway.

Over the summer of 2014, a Ukrainian counteroffensive into the areas around Sloviansk and Kramatorsk liberated big swaths of land, forcing Russian-backed forces to flee south-east to Donetsk.

What were the Minsk agreements?

The first peace plan to try to stop the fighting, the Minsk Protocol, was signed in September 2014. Just a month prior, more than 350 Ukrainian soldiers were killed in the Battle of Ilovaisk when Russian forces massacred Ukrainian fighters that were retreating through an agreed-upon corridor.

Ukraine, Russia, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) agreed on a 12-point ceasefire deal, with OSCE playing a monitoring role. Germany and France mediated the talks.

The protocol failed. Russia broke the ceasefire almost immediately, eventually reigniting the fight for the Donetsk Airport – one of the bloodiest and memorialized battles of Russia’s war in Donbas. Ukrainian forces also suffered huge losses in the Battle of Debaltseve the following winter.

A revised version of the protocol, Minsk II, was signed in 2015, but it also failed to stop the war for all the same reasons. Russia again breached the ceasefire and didn’t move back its heavy weapons, as was required.

Highly contentious provisions of the Minsk agreements included amnesty for all those involved in the fighting, decentralization in Ukraine to give more power to local authorities in Donbas, as well as local elections in Ukraine’s eastern territories.

Many believe that the agreements were null from the very beginning. Ukraine was already under attack by an outnumbered enemy, with no help from the West, and was thus pressured to sign even ill-advised deals to prevent further destruction.

Although the front line remained static after 2015, crossfire battles continued killing soldiers and civilians for the next seven years.

Why did Russia invade?

Russia’s invasions of Crimea and Donbas are seen by many as a reaction to Ukraine’s pro-Western course.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine was re-establishing itself as an independent, democratic state after decades of communist rule.

In 2004-2005, Ukraine’s Orange Revolution led to an overturning of presidential election results after people took to the streets to protest against election fraud. The candidate accused of rigging the election was no other than Kremlin-backed Viktor Yanukovych, later elected in 2010 and toppled in 2014 during the EuroMaidan Revolution – followed by the annexation of Crimea and war in Donbas.

Ukrainian society, slowly but surely, was coalescing around democratic ideals. Civil society grew larger and louder. Meanwhile, Putin’s Russia was moving towards authoritarianism and wished to keep Ukraine under its influence.

The Kremlin never truly accepted the independence of Ukrainian land, culture, and history. Ukraine’s rejection of Russian superiority and pro-European course, as well as the risk of spilling revolutionary ideals across the border, was seen as a catastrophe in the Kremlin.

The invasion of Donbas and Crimea is seen by many as an attempt to force Ukraine to give up its Western aspirations.

Is the war in Donbas a civil war?

The war in Donbas is not a civil war, as it was instigated and coordinated by Russia.

Although the Kremlin consistently framed the war as an internal Ukrainian struggle, international organizations and journalists have found direct proof of Russia’s involvement.

From the pre-war spread of secessionist sentiments to the fighting itself, all forces that fought against the Ukrainian government were fully or in part coordinated and financed by the Kremlin – and some simply were Russian, including the regular Russian army.

For instance, Bellingcat has documented Russian artillery attacks and Russian military vehicles in Donbas.

Amnesty International said in 2014 that there was “evidence that the fighting has burgeoned into what Amnesty International now considers an international armed conflict.”

An extensive report on Russia’s involvement by the D.C.-based think tank Atlantic Council also discusses the Russian army fighting in Donbas, supplying militias, and otherwise supporting the war.

The European Court of Human Rights said in a ruling that “areas in eastern Ukraine in separatist hands were, from May 11, 2014 and up to at least Jan. 26, 2022, under the jurisdiction of the Russian Federation.”

And in 2021, Russia was even caught admitting to stationing units of the Russian Armed Forces on Ukraine’s occupied territories in court documents.

What has been the cost of Russia’s invasion of Donbas in 2014?

Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts were industrial powerhouses before Russia’s invasion, with dozens of metallurgical, coal, chemical, and mechanical engineering enterprises that exported products all around the world.

The region brought around 15.7% of Ukraine’s GDP, and 14.7% of Ukraine’s population lived there, according to the London-based consulting firm Centre for Economics and Business Research.

The work of many of these enterprises came to a standstill as Russian attacks damaged industrial property, millions of locals fled the hostilities, and blockades between Ukraine and Russian-occupied territories abolished trade. The invasion also led to a fall in Ukraine’s international exports and foreign investment.

The Centre for Economics and Business Research found that Ukraine suffered a total of $102 billion in losses from Russia’s war in Donbas from 2014 to 2021. This means that annually, Ukraine was losing around 8% of its pre-war GDP just due to Russia’s invasion of Donbas.

At least two million people were forced to flee their homes because of the fighting. And roughly the same amount of people continued to live under Russian occupation – amid complete poverty, Kremlin indoctrination, and crossfire along the front, as Ukraine fought off continuous Russian attacks.

Thousands of Ukrainians were held hostage in Russian-occupied territories, including civilians. They were reportedly beaten, tortured, and held in prisons that many described as concentration camps.

At least 3,900 civilians and 4,200 soldiers died in Donbas as of February 2021, according to the U.N. Almost 20,000 civilians and soldiers were injured.