Opinion: Gogol, the Ukrainian Kafka that Russia couldn’t claim

Nikolai Gogol, a Ukrainian soul writing in Russian, exposed the dissonance of straddling two cultures, bound to one yet compelled by the other.

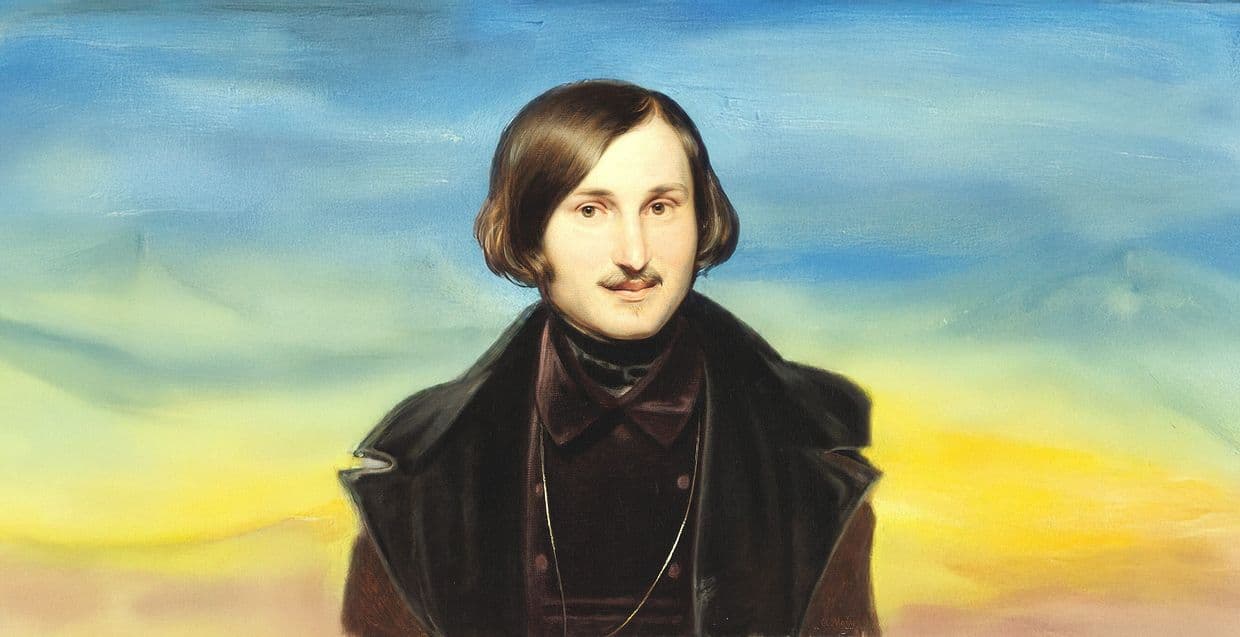

An illustration based on the portrait of Nikolai Gogol by Otto Friedrich Theodor von Möller. (The Kyiv Independent)

The question of Nikolai Gogol’s “belonging”—especially now, as Ukrainian and Russian cultures, long bound by an imperial past, are severing their ties before our eyes—remains a deeply painful issue for Ukrainians.

Gogol, one of the most gifted writers ever born on Ukrainian soil, loved Ukraine profoundly as a civilization, was Ukrainian-speaking by origin, yet chose Russian as his language of expression, thereby enriching Russian literature, whose importance not only for Ukraine but also for the world many of us are now trying to deny.

Yet literature is not a production line, and Ukrainians are not alone in grappling with such complex figures. French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, for instance, studied Franz Kafka not simply for his writing but for his unique position within world culture: a Jew from Prague, detached from Czech culture, fluent in German but distant from German civilization. Kafka constructed his own phantasmagorical universe…

Deleuze and Guattari applied the theories of French linguist Henri Gobard, who emphasized “four languages” that shape a writer’s work—the language of the land, the state, culture, and memory, or the “mystical” language.

For Kafka, Czech was the language of his land, German the language of state and culture, and Hebrew his mystical language. This framework led Deleuze and Guattari to describe writing as “minor literature”—not simply the literature of a national minority, but a distinct and otherworldly literature emerging within the same linguistic space. Kafka’s German was not that of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe or Friedrich Schiller, although his works are written in the “same” language.

Applying this lens to Gogol reveals something extraordinary. For him, Russian was the language of the state and culture, yet Ukrainian was simultaneously the language of his land and his mystical tongue—the wellspring of his genius! From the start, Gogol was a “minor literature” writer, striving to transition into the “major” and “universal” literary world—but, fortunately for us, he failed.

Strangely, this perspective returns us to an imperial, rather than Soviet, view of Gogol. Russians once saw him as their classic, celebrated with a grand monument on Moscow’s Gogolevsky Boulevard. But this was the Gogol of the Bolsheviks, a tool for “social criticism” and satire; this is why Joseph Stalin relegated his monument to a courtyard, closer to the writer’s final resting place.

Why, though, was there one Gogol in the Russian Empire and another in the Soviet Union? Early in his career, Gogol was viewed as a Ukrainian writer by Russia’s “respectable public,” which did not sit well with Nikolai Vasilyevich himself. Even when portraying Cossack loyalty in the novella “Taras Bulba,” he was accused of “idealizing” Ukraine. Gogol, failing to see the contempt some Russian peers held for his homeland, turned to write about Russia—but here, too, he met failure.

It wasn’t for lack of skill. “The Government Inspector” and “Dead Souls” are brilliant works. The problem lay in Gogol’s desire to write a grand poem about Russia; instead, his genius produced unflinching satire. Only Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin matched his biting portrayal of Russia, but there was a difference: Saltykov, a “Great Russian,” did not idealize Ukraine, whereas Gogol, a “Little Russian,” had portrayed Ukraine beautifully and rendered Russia harshly.

Gogol could not grasp the expectations of Russia’s cultural elite, who reproached the writer for not creating an ideal portrait of Russia and denigrating Ukraine. His inability to meet his demand drove him to destroy the sequel of “Dead Souls,” which could not yield an idealized Russia either.

Gogol could only respond through journalism, but here the democratic public, led by the literary critic Vissarion Belinsky, criticized his “reactionary” attitude. It was impossible to please both Belinsky’s and Russia’s cultural elite. No Russian writer would even attempt it!

But Gogol was neither fully Russian nor could he ever become one. He was the “Kafka” of Russian literature—a Ukrainian who cherished his homeland as a timeless myth, a dream, and yet viewed Russia, alien to him, with a realist’s unflinching gaze.

He wanted to see Russia as beautiful but found a monster instead. His Russian contemporaries could not abide this. They honored him with a monument that, like Gogol himself, would suffer forever—because he could not excise the “Little Russian” within him and become a “real Russian,” who scorns Ukraine and finds beauty in Russia’s grotesque figure.

The Bolsheviks, of course, twisted Gogol’s legacy, turning his “Little Russian” themes into mere folklore and his “Great Russian” themes into mere satire on the ruling classes. His portrayal of Russia was no longer seen as a Ukrainian’s view but rather a Marxist critique of exploiters. Yet these distortions have little to do with the true legacy of this Ukrainian genius.

Perhaps, then, we should recognize Gogol as a Ukrainian Kafka—a poet of Ukraine and the creator of a phantasmagorical Russia racing toward an unknowable destination, a man who showed us the vile world of Nozdyov and Sobakevich—a stark contrast to Ukraine’s idyllic landscapes. We should heed not the “revolutionary democrats” or Stalin, but those of contemporaries of Gogol who, even in his lifetime, saw him as a Ukrainian writer when he wrote “Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka” and “Dead Souls.”

Moreover, modern Russia is neither Stalin’s Soviet Union nor the Russian Empire under Nicholas I. Today, it would neither let Gogol mythologize Ukraine nor permit him to “vilify” Russia. It would spit Gogol out entirely.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent. This article originally appeared in Zbruch on Oct. 27, 2024, and has been translated from Ukrainian and republished by the Kyiv Independent with permission.