10 months after Mariupol theater bombing, family struggles to forget harrowing screams and dead bodies

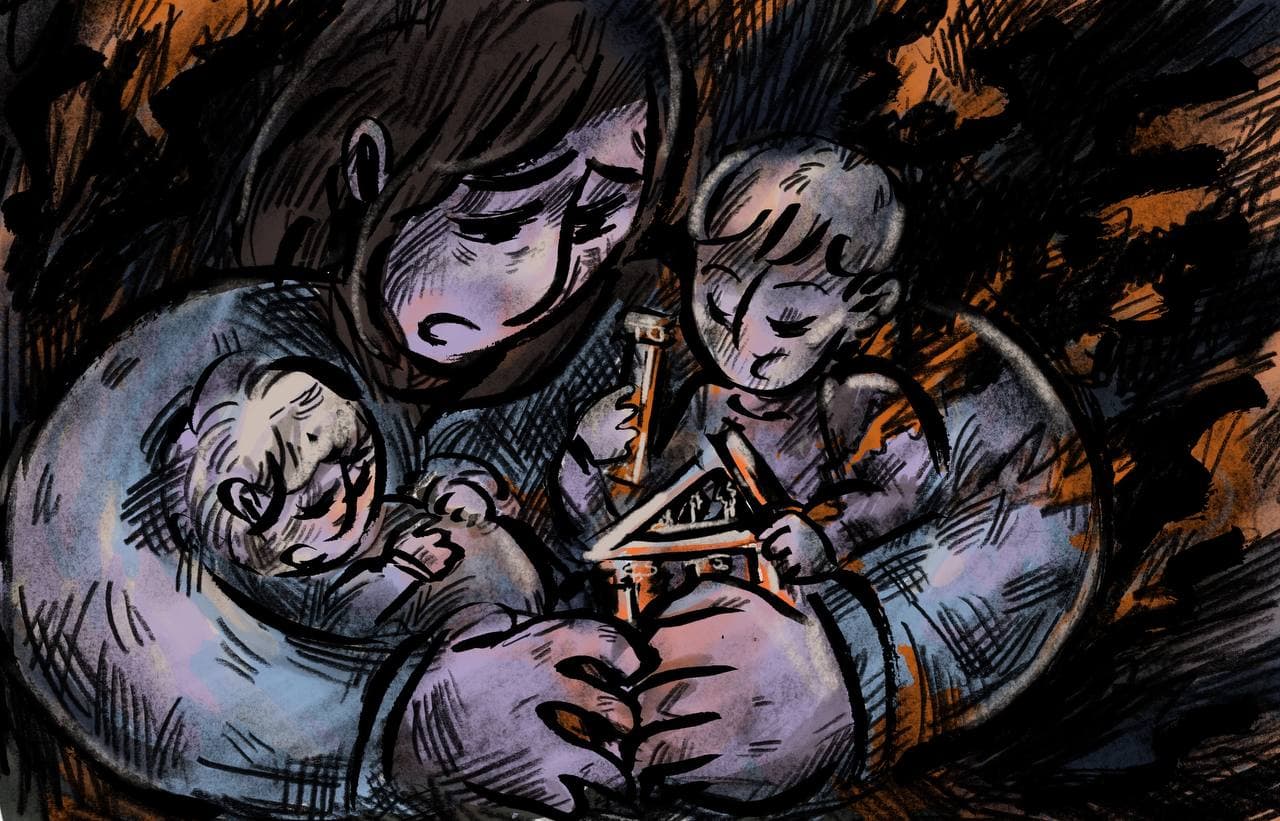

Ten months after barely surviving the Russian bombing of a theater in Mariupol, Viktoria Dubovitska is keeping a close eye on her seven-year-old son.

Artem remembers “almost everything” about what he saw in the March tragedy, the mother said. He tries not to talk about it, but unwanted memories keep crawling back as time passes by.

“He recently told me how scary it was not to be able to breathe in that room,” the 25-year-old mother said, referring to the spotlight room on the theater’s second floor where the family hid at the time.

When the explosion happened, a cloud of dust in the room made it almost impossible to breathe. It took a while for Dubovitska and her two little children to find each other due to a lack of visibility.

Russia’s airstrike on March 16 has likely killed 300-900 people hiding inside the Mariupol theater, according to different estimates, including an Associated Press investigation and figures by exiled local authorities. They were awaiting evacuation from the then-besieged Mariupol amid heavy Russian bombardment, according to Dubovitska.

Amnesty International believes that Russian military aircraft dropped two 500-kilogram bombs on the theater that fell close to each other and exploded simultaneously. The organization said there was no military site nearby, concluding it was a deliberate attack on civilians, which is a war crime.

Two months later, Mariupol, a southeastern Ukrainian city in Donetsk Oblast, was completely occupied.

Advisor to the Mayor of Mariupol Petro Andriushchenko told the Kyiv Independent that Russians had demolished the Mariupol theater in December and taken dead bodies elsewhere, killing hopes of ever identifying the victims.

Donetsk Oblast Governor Pavlo Kyrylenko said he predicts that “tens of thousands” were killed in Mariupol during the brutal months-long siege, but he could only give rough estimates since the city is still occupied by Russia. Much of what was once a vibrant port city, with a pre-war population of 450,000, was destroyed.

Dubovitska is extremely worried about Artem, who sometimes loses control of his emotions. Her family moved to a quiet village in central Ukrainian Cherkasy Oblast and switched off the news to “start from scratch,” but nothing helped to erase the bombing horror.

Millions of Ukrainian parents are trying to help their children cope with the mental health consequences of the war while struggling with their own scars of the war. For many, therapists are not accessible due to logistics and financial issues, leaving parents responsible for guiding their little ones through this daunting task of healing from trauma.

Bloody siege of Mariupol

Artem was once an ordinary child who loved his toy collection and enjoyed playing outdoors in Mariupol, but everything changed as Russian troops started to destroy his city, Dubovitska said.

Until the morning of March 16, Artem kept asking his mother why Russians were bombing the city he loved so much.

“Why are they doing this to us? What did we ever do to them?” Dubovitska remembers Artem asking her repeatedly while they were still in Mariupol.

After witnessing the Mariupol theater bombing, Artem rarely asks questions. He still occasionally goes back to his memories of the tragedy.

“He remembers how we rushed down the stairs, how a boy (his friend Nazar) shouted, ‘where is my mother? We will all die,’” Dubovitska said.

Artem still asks what happened to his friend Nazar. The mother tells him that she has not heard anything about Nazar or his mother yet.

Artem looked shocked as the family was escaping the bombed-out theater, sprinting because Russian forces were relentlessly attacking the city, Dubovitska said. He was barely keeping up the pace as he held his mother’s hand with one hand and his pants with another because he had lost so much weight.

On their way to a school-turned-shelter in Mariupol, Dubovitska said they saw a man digging graves outside to bury about five bodies that layed next to him.

“He (Artem) saw the corpses; he saw torn-off body parts,” Dubovitska said.

Ten months after escaping Mariupol, Artem keeps asking his mother if Russian troops would come to him again and destroy everything, as they did in his hometown, Dubovitska said.

Even though she tried to reassure Artem that he is safe in the village in Cherkasy Oblast, the boy is prepared for any possible sudden change of event. He knows exactly where his parents store important documents at home.

“The child already knows things he definitely should not know at the age of seven,” Dubovitska said.

Whenever Artem hears a loud sound, he immediately hides behind a wall and takes his little sister.

“He always takes away his sister,” Dubovitska said. “He doesn’t just think about himself.”

The boy is very receptive to a helicopter flying over the village – he told his mother that he heard the same sound right before the Russians bombed the theater.

At school, it’s still difficult for Artem to hear air raid sirens. He also struggles to hide in a shelter, forcing him to recall how the family hid in Mariupol.

When spending time with kids his age, Artem tries to avoid talking about what he remembers from Mariupol, Dubovitska said. Some of his friends’ parents asked him not to discuss his trauma with their kids.

“He is trying to somehow behave like ordinary children, who have not experienced or seen all this,” Dubovitska said.

Survivor’s guilt

While caring for her two small children, Dubovitska is also coping with her own psychological scars.

Dubovitska said she could never forget the screams she heard inside the theater.

Seeing motionless bodies and wounded civilians – children, women, and the elderly – yelling, “help, help,” is stuck with her forever.

For a month and a half, Dubovitska felt guilty that she didn’t stay at the theater to help the wounded – and ran out to save her children instead.

“At first, I felt guilty because I knew there were people there, and, probably, I could have helped someone,” Dubovitska said. “I didn’t help anyone there, and I didn’t stop, because I only thought about my children.”

After some time had passed, Dubovitska found out through a friend that Russian forces launched more strikes on the theater afterward. She believes it because the photos of the theater captured later that day showed much worse damage than what she remembers seeing in person.

“I told myself that I probably did the right thing after all by taking just my children out (of the theater) and saving them,” Dubovitska said. “I could have been killed, and my kids could have been killed. So now, I don’t regret it.”

Dubovitska still has relatives in Russian-occupied Mariupol, who she can’t stop worrying about – her brothers, aged 22 and 29, and the elder’s children.

Her 83-year-old grandmother died from a stroke in the summer due to poor health care in Mariupol, Dubovitska said. The shortage of food and clean water made the situation worse, she added, referring to what her younger brother told her.

The grandmother “was already very thin, she was in poor condition, and, there were no doctors, no medical care,” Dubovitska said.

She last saw her grandmother days before Feb. 24, but she said she was shocked at how quickly the elderly’s health degraded since then when she saw a photo taken a few months later.

While coping with grief, Dubovitska said she couldn’t help but regret not seeing her grandmother one last time before fleeing Mariupol. Her mother died when she was 13, so her grandmother was raising Dubovitska after that.

Meanwhile, she cut all contact with her father, a Russian living in Russia.

As Russian forces began incessantly bombing Mariupol, the father told Dubovitska in late February that they were “not targeting civilian areas and they are setting you free,” repeating a widely spread Russian propaganda.

Despite everything, the young mother said she needed to stay strong.

“I now have two children in my arms, and no one needs my children, except for myself – and my husband,” Dubovitska said. ”So now I try not to think about it at all.”

Moving to unfamiliar place

Immediately after fleeing Mariupol, Dubovitska reunited with her husband, who was working abroad until the full-scale invasion began on Feb. 24.

As refugees, the family was given a two-week-long free stay at a shelter in the western city of Lviv by volunteers. But then, their stay expired.

Struggling to find accommodation in western Ukraine, where rent prices have skyrocketed amid an influx of refugees fleeing war, Dubovitska decided to settle for an offer at a small village in Cherkasy Oblast.

The Mariupol family is still going through financial hardship.

Dubovitska receives social welfare of Hr 8,000 (about $220) monthly for herself and two children. Internally displaced adults in Ukraine receive Hr 2,000, and kids get Hr 3,000 monthly.

While Dubovitska said she couldn’t work because she had to take care of the kids, her husband is struggling to find a decent job in a small village.

But by all means, Dubovitska tries to make it work.

At first, the family had to take an offer on the online website OLX to live with a woman offering a free stay in exchange for doing all the housework – from cleaning to cooking – and taking care of her kids and farm.

Dubovitska said her husband spoke against the host woman one day, and she kicked the family out at midnight.

But thankfully, a neighbor welcomed the Mariupol family inside and helped the four find an empty house to stay in – even if it had no water at first and still no heating or toilet (they use a portable plastic one now).

Dubovitska said her family misses city life, but it’s not financially feasible to afford accommodation and living costs.

Artem asked his parents in the summer whether the family could move to a city because the village doesn’t even have a playground.

But more than anything, the boy is eager to return to Mariupol, and live the life he once had.

Artem still doesn’t know the scale of damage in his hometown because he has only scene photos of the damaged home – and not the rest of the city, according to the mother.

“On the one hand, I do not want to show (Artem) the ruins that are now there,” Dubovitska said. “But, on the other hand, he does not understand… that there is nothing left (of the city).”

“He still hopes and believes that we will return to Mariupol and there will be the same life he had before,” Dubovitska said.

___________________________

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Asami Terajima, the author of this article. Thank you for reading my story till the end. The Kyiv Independent team has been selflessly covering Russia's brutal war against Ukraine since day one, doing our best to keep the world informed about the latest developments at home. Please consider supporting the young and driven newsroom by becoming our patron.