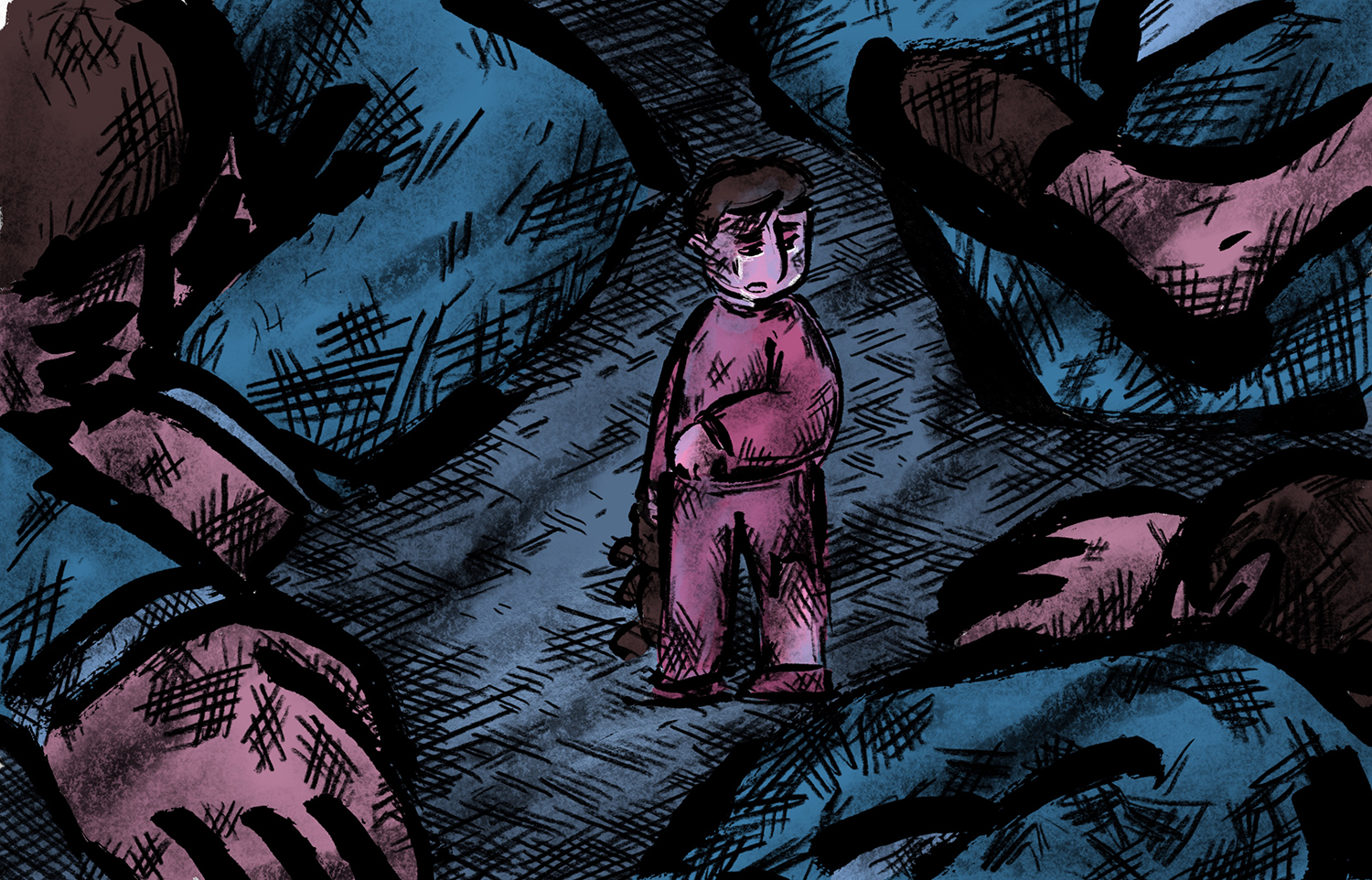

‘Uncertainty and despair’: War taking heavy toll on mental health of Ukrainians

Viktoriia Borodai can not recall the last time she experienced "real joy."

She has lived in "uncertainty and despair" ever since Russia's all-out war forced her to flee Kramatorsk, her hometown in Donetsk Oblast, last March.

Seeking shelter in different towns across Ukraine and watching how Russian troops bombard her beloved hometown emotionally drained Borodai so badly that she now struggles to get out of bed in the morning.

She also cries a lot when watching the news or thinking about her life before the war.

"I feel how strongly the war has affected my mental health. I don't know how everyone else is doing, but I don't feel well," Borodai told the Kyiv Independent.

"It is difficult for me psychologically. In recent months, I have been thinking of turning to a psychiatrist or taking antidepressants," she says.

Borodai is not the only one who struggles: Russia's all-out invasion left millions of Ukrainians displaced. Many have lost their loved ones or faced violence while living under Russian occupation.

The World Health Organization (WHO) says that 22% of people who have "experienced war or other conflicts in the previous 10 years will have depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia."

As for Ukraine, WHO expects that roughly 9.6 million people "may have a mental health condition."

In June last year, Health Minister Viktor Liashko forecasted that around 15 million Ukrainians would need psychological support in the future, and up to 4 million would require prescribed medical treatment.

"Even those who were able to withstand the first months of the war will suffer mental exhaustion because getting used to being in a constant war can also have a negative impact on mental health," Liashko said.

In a comment to the Kyiv Independent, the Health Ministry said that experts estimate that 40-50% of the Ukrainian population would need various forms of psychological support: "In particular, 1.8 million people among military personnel and veterans, 7 million among older people, and about 4 million of children and teenagers."

First Lady Olena Zelenska says the cost of Ukrainian "invincibility" is not just the lives of military and civilians but also the "mental health of the entire nation."

"Most Ukrainians have already suffered from anxiety disorders, and now not only military personnel but also civilians in towns and villages have PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) — from children who saw the death of their parents to adults whose whole family was killed by the Russian shelling. From people who survived abuse during the occupation to those who lost arms, legs, and health," Zelenska wrote on Facebook in June.

Stress and trauma

Hearing loud explosions for the first time and seeing the destruction, even on photographs, hit many Ukrainians very hard in the first hours of the full-scale invasion.

Psychotherapist Olha Ishchuk says she received many calls from her clients on Feb. 24, 2022.

"There were many panic attacks and anxiety," Ishchuk says.

She had to arrange short "emergency" sessions to provide the clientele with mental health assistance. During the 15-minute calls, Ishchuk taught people specific actions such as breathing techniques and physical exercises to improve their "emotional, physical, and mental state."

"I needed to help people there and then," she says.

Another psychiatrist, Sofiia Vlokh, says many people, herself included, felt anxious at the beginning of the war, as they were overwhelmed with "uncertainty and feared for their future." It was a normal reaction, she says.

"It was our reaction to the unknown… To the events we could not change."

As the Russian invasion continued with all its destruction and war crimes, it weighed ever harder on Ukrainians' mental health, experts say.

According to a survey published by the Health Ministry last September, "over 90% of respondents had at least one symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder."

Vlokh says many people are coping with various anxiety disorders and trauma-cased issues: "The more traumatic and stressful the events are, the more anxious the thoughts are," she says.

Ishchuk notices more people experiencing apathy and having "no power, no resources at all, even to continue living." She also gets many requests from people complaining that they can no longer experience joy, just like Borodai.

For many, there is also an "extreme feeling of guilt" for doing or feeling something pleasant during the war, Ishchuk says.

"Unfortunately, suicidal behavior and suicidal thoughts have become more frequent."

Various sleep disorders are also among the frequent problems experienced by Ukrainians. Many people struggle with insomnia, or on the contrary, waking up, Ishchuk says.

Yuliia Novik, 39, from Kyiv, barely slept at night last year. Lying in bed, all she could do was stare at the ceiling, trying to cope with countless anxious thoughts and worrying about her loved ones.

"Having no desire for anything, the uncertainty of the future — all of that was running through my mind over and over again," Novik says.

"I could fall asleep only for a few hours in the morning. That was when I simply dozed off."

Russia's all-out war "ended" Novik's usual life: She lost her job and was forced to flee Kyiv with her parents and 10-year-old son to start life from scratch in a foreign country.

Her severe sleep problems came from stress and soon resulted in a general health decline, constant anxiety, and occasional panic attacks.

"I felt that my nervous system simply could not cope with all that," Novik says.

Seeking help

It's normal to feel anxious during an imminent threat like an air raid alert. But when a person struggles with anxiety, apathy, depression or inability to concentrate for over two weeks, it might be time to see a therapist, according to Vlokh.

"We have many free psychological services, and from my experience, people now really want to take care of their mental health," Vlokh says.

Kyiv-based nonprofit UA Mental Help provides free psychological assistance. Founded shortly after the start of the full-scale invasion, the charity started off posting self-care tips on social media but now also provides consultations with therapists.

The charity's founder, Olha Yudina, says they have received over 4,700 requests from Ukrainians since the start of the full-scale war, over 3,000 of which were made in 2023.

"We see a certain demand for psychological assistance," Yudina says.

Seeking psychological help was not common in Ukraine before the 2022 invasion. In a 2017 report, the World Bank concluded that Ukraine’s "poor mental health" was tightly interconnected with poverty, unemployment, and feelings of insecurity," adding that it was also compounded by the effects of Russia’s war in Donbas.

"There is a lack of community level mental health care and limited provision of mental health care and support by non-specialized staff such as general doctors and family physicians," reads the report.

Yudina notes that over 50% of their clients have applied for psychological assistance for the first time in their lives and that the war impacts people of all ages: A couple of weeks ago, the team received a request from a 90-year-old man.

According to Yudina, "excessive fear," anxiety, and depression symptoms are among the most common issues people seek help with.

UA Mental Help tries to increase well-being and lower psychological distress to the point where it does not prevent a person from "living and being a part of society.”

"Because depending on how people feel, that's how they perceive the world," Yudina says.

Many businesses in Ukraine have also launched mental health support programs for their employees.

The Ukrainian branch of the international IT company MobiDev, for instance, started such a program for their employees last March, offering them some guidelines, lectures with psychologists, as well as options to “rest and recover without losing a job,” such as the sabbatical leave, the company’s HR team leader Anastasiia Khlopko told the Kyiv Independent.

"People's condition is greatly influenced by their ability to rest, so we remind them about vacations," Khlopko says. "It is possible to take sick leave, even if a person feels bad not only physically but also mentally."

On the state level, First Lady Zelenska launched a campaign called "How are you?" to raise awareness of mental health care's importance and share some self-help recommendations. One can also find various hotlines for psychological assistance on the campaign's website.

There is an online map with medical facilities providing such services across Ukraine. According to Health Minister Liashko, over 17,000 Ukrainians have applied for state-funded psychological support since the start of 2023.

Even though professional help is often crucial, there are ways people can help themselves on their own too.

Vlokh says connecting with loved ones helps a lot in many cases.

"Humor is also a great tool to feel better," she says.

Meditations, breathing techniques, and simple physical exercises can help relieve stress. Also, not thinking about the future but doing something that has an immediate impact, like making a donation, might help as well, according to Vlokh.

Novik says that after fleeing abroad, she first gave herself some time to breathe. Then, she started walking a lot and spent most of the time with her son. Soon, she could again listen to music and do sports — something she enjoyed a lot before the war.

She has recently gone into therapy and finally started sleeping at night.

"Do not expect that you will simply stop suffering at one point," Novik says.

"Find something to distract, like painting or learning, and take small steps to start living again."

Worth fighting for

Despite the many struggles posed by Russia’s aggression, experts say Ukrainians have adapted to living in wartime conditions.

"Yes, there are more disorders, but in general, if you look at Ukrainians, our psyche is very flexible," says Vlokh.

"I think everyone has already found their own way of staying balanced."

Psychiatrist Anna Vashchuk, who manages psychological services at UA Mental Help, says that around 50% of people who experienced trauma can even have post-traumatic growth.

"These (traumatic) events change our functioning so much, they affect our perception of life so much that sometimes we can see something important in our life and even improve it," Vashchuk explains.

However, to have that post-traumatic growth, people need to start taking care of their mental health now, according to Vashchuk.

She says it's crucial for people to understand that the more quality help they the more supported they will feel and the more likely they are to have post-traumatic growth in the future.

"And so our country will grow, even during such painful events," Vashchuk says.

If mental health is neglected, post-war Ukrainian society might expect suicides, depression, behavioral disorders, and aggression on a massive scale, according to Ishchuk.

She also estimates that after the war is over, there might be a "new wave" of psychological disorders if all Ukrainian territories are liberated and more Russian war crimes are revealed.

"But if we plan and forecast correctly, it will be possible to reduce the consequences," she says.

Military psychologist Andriy Kozinchuk says Ukrainians need to learn to take care of themselves since "now we take care of everything but ourselves."

"We still lack the awareness that we need to fight for our mental health because it is worth it," Kozinchuk says.

"If you don't work on it, you will be unhappy," he goes on. "We do deserve to be happy."

Note from the author:

Hi! Daria Shulzhenko here. I wrote this piece for you. Ever since the first day of Russia's all-out war, I have been working almost non-stop to tell the stories of those affected by Russia’s brutal aggression. By telling all those painful stories, we are helping to keep the world informed about the reality of Russia’s war against Ukraine. By becoming the Kyiv Independent's member, you can help us continue telling the world the truth about this war.