Mykhailo Fedorov and his team “make things happen,” Time magazine wrote when it selected Fedorov as one of its 100 emerging world leaders in September.

“It is like it is in his DNA to take action,” his profile read.

Fedorov, Ukraine’s 31-year-old deputy prime minister and minister of digital transformation, keeps it modest about making it onto Time’s list.

“I was pleasantly surprised,” he said in an interview with the Kyiv Independent. “It motivates me to keep working.”

Wearing a black hoodie, the youngest member of Ukraine’s Cabinet spoke about the role of tech during the war and his accomplishments on the digital battlefield via Zoom from his office in Kyiv. The old wooden furniture in the room – a holdover from previous, old-school governments – stands in stark contrast to Fedorov’s tech-savvy personality.

For balance, Fedorov decorated his space with children's drawings, books, and a neon sign reading "Diia" – the name of the state mobile application launched by Fedorov and his team to achieve President Volodymyr Zelensky's promise to digitize government services.

Fedorov's wartime portfolio is impressive: He helped bring Elon Musk’s satellite internet Starlink to Ukraine’s front line, pressured global tech companies to stop operating in Russia, and lobbied to legalize cryptocurrency so that Ukraine could accept donations to the military in crypto.

Unlike other government agencies that are often drowned in bureaucracy, Fedorov organized his Ministry of Digital Transformation to operate like a startup: young and entrepreneurial civil servants put forward ambitious ideas – some so ambitious they are unfeasible – and then seek funding to implement them. “Only 10% of our ideas take off,” Fedorov said.

Before the war, Fedorov’s dream was to make Ukraine “the most convenient state in the world.” To do so, he worked to move government services, such as paying taxes and receiving unemployment benefits, online. The fruit of his labor is Diia, now used by more than 18 million people out of Ukraine’s 41 million adult population.

Fedorov also pushed for the legalization of cryptocurrencies in Ukraine and introduced a special taxation system – Diia City – for tech firms and startups. The tech community is split on this initiative — some consider it a threat to the current system where tech specialists pay a favorable 5% revenue tax if they’re registered as private entrepreneurs.

Technology has proven vital in times of crisis, whether it be the Covid-19 pandemic or war, Fedorov said. And Ukraine, partly thanks to his ministry’s efforts, was ready to use tech to fight against the enemy and support the economy.

The innovations gave Ukraine a real edge against the heavily outdated Russian army, which mostly uses military equipment left over from the Soviet era. By the third month of the war, for example, when the Ukrainians had already started using Starlink for communications, many Russian soldiers were using ERA cryptophone system, which did not work in most regions of Ukraine and could easily be cracked by Ukrainian intelligence.

As Russia continues its war, one of Fedorov's priorities now is to turn Ukraine into the center of military tech development and production. “I want more Ukrainian tech companies to help kill Russians,” he said, smiling.

Winning the war with tech

To understand what technologies Ukraine needs to win the war against Russia, Fedorov consults with the Defense Ministry and the military.

Among the most sought-after tech in the war zone are internet and mobile communications, satellite imagery, reconnaissance and kamikaze drones, and data analysis systems.

Fedorov's ministry has already helped bring some of this technology to the battlefield.

As the story goes, Fedorov managed to bring Starlink satellite internet to Ukraine with a single tweet addressing Elon Musk. That’s not entirely true. Ukraine had been in talks with the American spacecraft manufacturer SpaceX, the owner of Starlink, even before the February invasion, but legal problems and bureaucracy hampered the process.

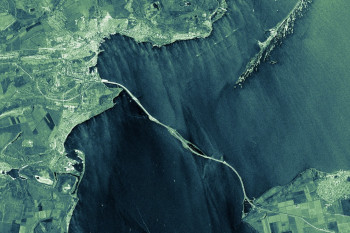

Mykhailo Fedorov, Ukraine's minister of digital transformation, poses for a photo near the Starlink satellite internet kit on Feb. 28, 2022. (Mykhailo Fedorov/Telegram)There are now about 20,000 Starlink terminals in Ukraine, according to Fedorov. Some of them were donated by Musk, others – gifted by the EU countries or paid for by the U.S. government.

Starlink allows access to the internet even during power outages or in the absence of other internet infrastructure. It is also more secure than other types of communication.

Fedorov has always praised Musk for helping Ukraine, so he was disappointed when recently the SpaceX founder suggested on Twitter that in order to achieve peace with Russia, Ukraine should adopt a neutral status, abandon its bid to join NATO, and stop trying to regain control over the Crimean Peninsula, annexed by Russia in 2014.

“I hope that these are not his views, but a failed attempt to engage his audience in the discussion of important world issues,” Fedorov said.

He does not consider Musk’s words a betrayal of Ukraine.

“As long as he continues to help Ukraine, we'll assume this was just an inappropriate tweet,” Fedorov said.

Mykhailo Fedorov, Ukraine's minister of digital transformation, during his visit to the training school for drone operators Dronarium on July 29, 2022, in Kyiv. (Mykhailo Fedorov/Telegram)Apart from Starlink terminals, Fedorov helps supply the army with drones, which Ukraine needs in large quantities. Together with other ministries, he co-founded a project called the “Army of Drones” that raises money to purchase drones and train specialists to operate them.

Over the past three months, the “Army of Drones” signed contracts for $51 million to buy 1,000 drones for Ukraine’s Armed Forces.

The “Army of Drones” makes the process of bringing drones to the battlefield fast, going around the bureaucracy associated with regular procurement.

Drones used on the battlefield must be licensed and tested to ensure they are safe. New Ukraine-made drones usually don’t have this license, as they have not passed military tests.

Fedorov said he will try to make the process of testing drones and obtaining a license faster.

Fighting a war on the digital front

Before becoming Ukraine’s first-ever digitalization minister, Fedorov headed a marketing agency and ran the digital side of Zelensky’s campaign in the 2019 presidential race.

When Russia’s full-scale invasion started in February, Fedorov, like the whole Cabinet, went into the war mode. He used his digital marketing experience to rally support for Ukraine abroad and to urge global tech firms, including Google, Netflix, and Apple, to suspend their services in Russia.

“No celebrity, let alone nation, has ever been more effective than Ukraine at calling out corporate brands to name and shame them into acting morally,” said Peter Singer, a professor at the Center on the Future of War at Arizona State University, in an interview with The New York Times.

It’s hard to say what exactly led to the mass tech exodus from Russia – Fedorov's letters, global outrage, financial sanctions, or a mix of all factors. But as of October, hundreds of international tech companies no longer operate in Russia, including Samsung, Payoneer, Adobe, Sony, TikTok, and Spotify.

Fedorov's next goal is to encourage these businesses to help rebuild Ukraine.

Companies such as Google, Amazon, Apple, Oracle, and Microsoft are helping Ukraine with data protection, cybersecurity, and online education. The fintech services Revolut and PayPal, which Fedorov has been trying to bring to Ukraine for years, have finally started providing some payment services for Ukrainians and are poised to expand their operations in the country, Fedorov said.

“The war opened up a new digital Ukraine for global tech firms,” Fedorov said. They see that the Ukrainian tech industry continues to grow even during the war, and the Ukrainian government is interested in making Ukraine more attractive for foreign tech companies.

In October, for example, the Ukrainian parliament approved a bill that allows foreign tech specialists to register businesses and pay taxes in Ukraine online.

Fedorov uses his popularity and global interest in Ukraine to maintain close ties with global tech firms and collaborate with them on new projects.

As such, he wants to add a voice assistant to the Diia app to make it accessible to people with disabilities and visual impairments. For this, Fedorov plans to collaborate with Amazon, which has Alexa voice assistant.

Preventing brain drain

The tech industry is one of the few that is still growing and that brings money to the state budget, according to Fedorov. During eight months of the war, IT exports grew by 16% to $287 million.

But there is one problem: IT is a global business that usually requires a lot of travel, as most Ukrainian tech firms work with foreign clients or have offices abroad. Due to martial law Ukrainian men between the ages of 18 and 60 can’t leave the country.

To help IT businesses grow further, Ukraine must solve this problem, according to Fedorov.

Ukrainian lawmakers have already submitted the bill to allow the men who work in tech to temporarily leave the country, but the government has not been able to adopt it for several months.

“This is a complicated procedure and it’s not up to our ministry to make it easier,” Fedorov said.

It likely doesn’t help that Zelensky himself has been reacting harshly to suggestions to lift the ban for men of draft age to leave the country.

Fedorov says that it is in the government's interest to help develop the Ukrainian tech industry, as it will help in the country's post-war recovery. “The more people get into IT now, the faster we can strengthen our economy,” he wrote.

To encourage more people to work in IT, Fedorov has recently launched the IT Generation project to teach 2,000 Ukrainians basic programming for free. According to Fedorov, more than 200,000 Ukrainians applied for this program. Ninety percent of applicants have never worked in IT.

He would like to accept more students, but the budget is limited to $1 million granted by Ukrainian and international donors, including Binance Charity, USAID and the UN Development Program.

As of early 2022, Ukraine had about 300,000 people employed in the tech sector. About 57,000 of them have moved abroad because of the invasion.

Yet Fedorov doesn’t think that Ukraine is at risk of brain drain – he believes that many of them will return out of patriotism, to help rebuild their country.

“And for those who don't have enough patriotism to come back, we will continue to develop the cool brand of Ukraine that both local and foreign techies will want to be a part of,” Fedorov said.

And for those who work with Fedorov, skipping town seems unlikely. "He was one of the reasons why I switched from business to civil service," Stas Prybytko, head of mobile broadband development in Ukraine’s Ministry of Digital Transformation, told the Kyiv Independent.

"Mykhailo defends our projects when someone tries to slow them down, and unites the entire team to achieve a common goal,” Prybytko said.

Cyber warfare

Russian hackers have been attacking Ukraine in cyberspace since the first days of the invasion. As of August, more than 1,000 cyberattacks have been recorded in the country, targeting government websites, financial services, and energy facilities.

Fedorov’s ministry has also suffered. The most popular types of attacks, according to him, are phishing, used to steal user data, and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS), where hackers flood websites with junk traffic to knock them offline.

To protect itself, the ministry has hired so-called “ethical hackers” who attack government systems to find and fix bugs that Russian hackers can use to break into systems.

Fedorov said that his team has managed to repel Russian cyberattacks so that users didn’t feel their impact. The Diia service has been targeted multiple times, but has never stopped working, according to Fedorov.

To fight back against Russian hackers, Fedorov has called on Ukrainians to join the IT Army, a group of cyber volunteers, who attack Russian websites. Under the IT Army's guidance, even people without tech skills can participate in the digital war, giving them a feeling that they are helping Ukraine to fight Russians too. The IT Army is an independent organization and is not controlled or funded by the state.

Before the full-scale invasion, Ukraine expected Russian hackers to actively attack Ukraine's energy infrastructure, as happened in 2015 when an attack by the Russian hacker group Sandworm hit Ukraine’s power grid, causing power outages for over 225,000 people.

But this time it didn't happen: Most Russian cyberattacks have been chaotic and unsuccessful, rarely causing much damage, according to Fedorov.

“The main achievement of Ukraine in this cyber war is that we still communicate online and that all our state computer systems are working as usual,” Fedorov said.

And while Russian missiles continue to destroy Ukrainian cities, and hackers try to break into government systems, Fedorov plans to continue with the digitalization of Ukraine, in particular, its defense sector.

“I think we can become a military-tech center. We make a lot of cool products that we can share with other countries,” he said.