How fragmented sanctions prolong the war and empower Russia’s defense industry

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin visits Uralvagonzavod, the country’s main tank factory in the Urals, in Nizhny Tagil, Russia, on Feb. 15, 2024. (Alexander Kazakov / Pool / AFP / Getty Images)

Mariya Chukhnova

International security and stability expert

About the author: Mariya Chukhnova is an international security and stability expert at The Critical Mass, an international security think tank based in Alexandria, Virginia.

Nearly four years into Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, its military-industrial complex continues to function almost undisturbed.

Despite multiple rounds of sanctions and export controls, Moscow’s defense factories are running at full tilt, producing missiles, tanks, drones, and ammunition at growing rates. The gap between the scale of Western sanctions and their actual effect on Russia’s war economy remains wide — and dangerously so.

Russia’s military industry has adapted through consolidation, camouflage, and the exploitation of loopholes. Many defense companies that appear to be liquidated were simply reorganized under new names. They preserve both production lines and personnel.

The Russian state, drawing on its Soviet-era legacy of redundancy and command economy management, has learned to survive isolation by shifting production, centralizing supply chains, and mobilizing workers.

This resilience exposes a central flaw in current sanctions policy: The measures are broad in scope but weak in focus.

They punish what is visible: large defense conglomerates and political elites, while leaving the deeper supply network intact. Russia’s ability to keep manufacturing weapons depends on thousands of small and mid-tier suppliers that remain unsanctioned, particularly those providing metals, chemicals, and components for propulsion and guidance systems.

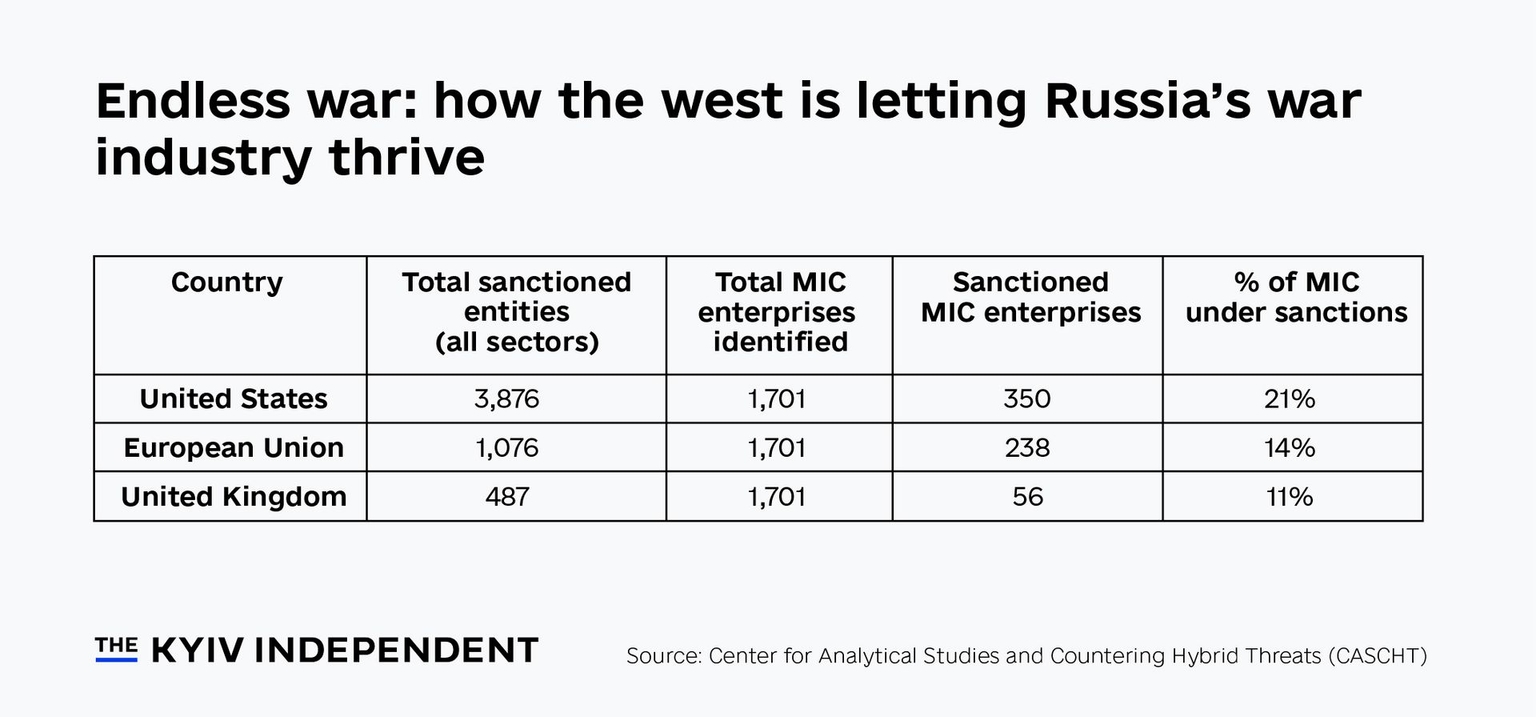

The newest data compiled by Ukraine’s Center for Analytical Studies and Countering Hybrid Threats (CASCHT) shows that nearly half of Russia’s defense-related enterprises remain outside Western sanctions lists.

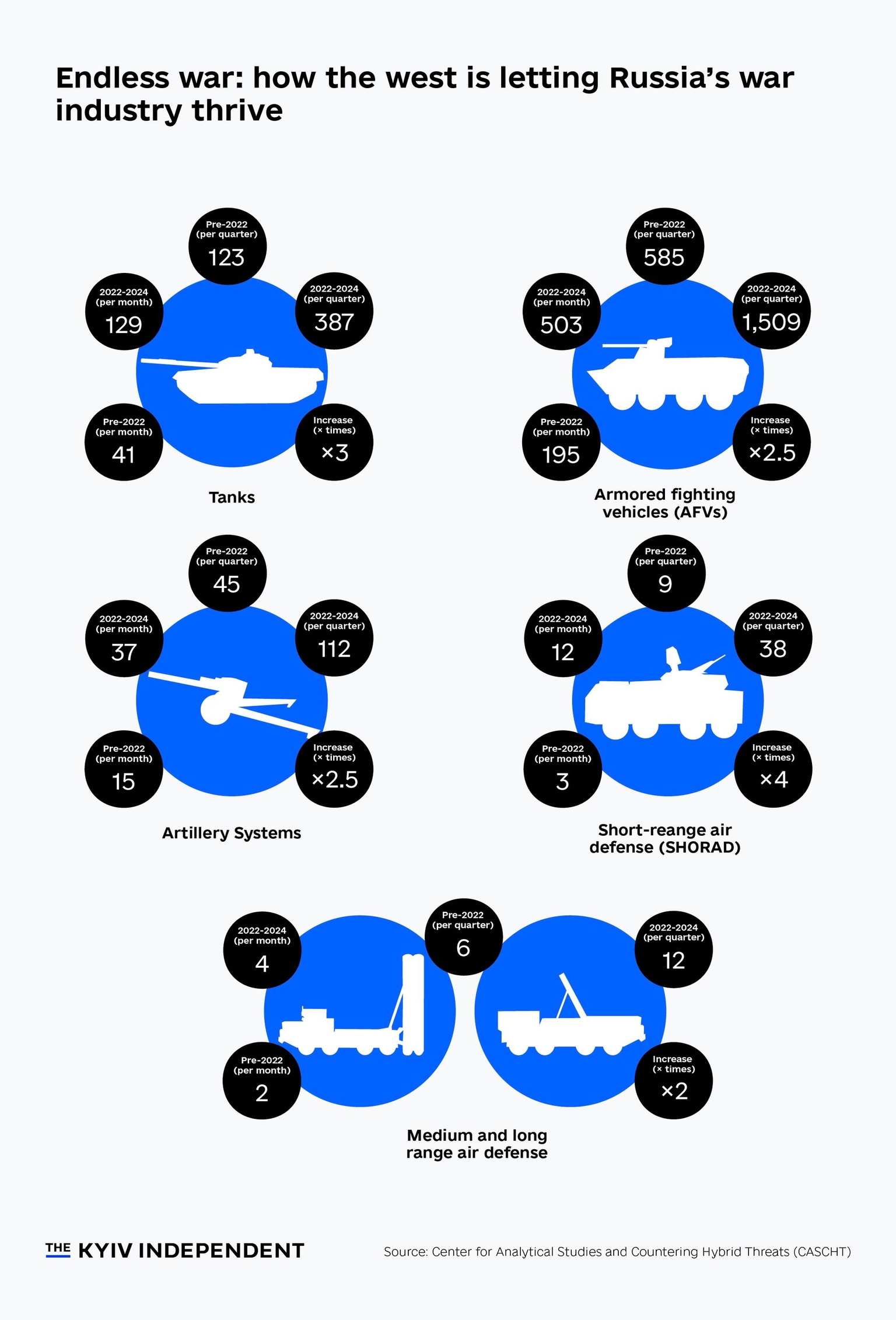

Production of tanks and armored vehicles has tripled since 2022, while the number of artillery and air-defense systems has increased several times over. Despite losses of Western components, imports from China, Central Asia, and the Middle East have filled the gaps, often routed through Kazakhstan, Armenia, and the UAE.

The Russian system treats isolation as a challenge to be managed, not an existential threat. The result is a “mobilized economy,” where survival replaces innovation and quantity substitutes for quality. In that context, partial pressure is not deterrence; it is adaptation fuel.

The weakness of the current sanctions architecture lies in its fragmentation, as major allies, such as the U.S., the EU, and the U.K., remain inconsistent in coverage and enforcement.

The numbers reveal a structural imbalance. The United States lists thousands of Russian entities, yet only a small fraction is directly tied to the defense sector. Brussels and London follow the same script: focusing on high-profile corporations while ignoring the broader industrial network that sustains production.

The result is a patchwork system of sanctions that Moscow easily exploits.

Divergent definitions of “dual-use goods,” inconsistent licensing regimes, and limited intelligence sharing allow Russia to reroute trade through third countries.

A banned titanium supplier in Europe may continue shipping via Turkey; an electronics exporter sanctioned by the U.S. can resurface in Kazakhstan under a new name. Sanctions designed to isolate end up encouraging innovation in evasion.

How to end the war

Sanctions are the only sustainable tool of nonmilitary pressure available to democracies, but they must evolve from punitive symbolism to strategic precision.

The next phase must strike at the raw materials that underpin Russia’s war economy — from manganese and cotton cellulose to titanium and the chemical precursors critical for explosives and aerospace manufacturing. Without tightening access to these inputs, Russia’s defense sector will continue to operate with alarming resilience.

Just as crucial is disrupting the logistics that keep this machinery running. Transport intermediaries, ports, and shipping-insurance services form the arteries of trade flows, allowing sanctioned goods to move with ease.

Finally, enforcement must move beyond Western borders. Moscow’s ability to reroute trade through third countries — particularly China, Kazakhstan, and the UAE — has minimized much of the sanctions regime’s intended bite.

Equally vital is institutional coherence: a joint transatlantic sanctions mechanism capable of real-time coordination, shared intelligence, and dynamic listing updates. Without unified action, sanctions will remain reactive and piecemeal — strong in rhetoric but weak in execution.

Sanctions alone cannot win a war, but no modern war can end without them. The survival of Ukraine, and of the entire region, depends on both Western weapons and the systematic paralysis of Russia’s capacity to produce its own.

Every day that Russian defense plants continue to operate is another day Moscow refines its warfare, learns from its failures, and becomes more adaptable to the modern battlefield.

To change that equation, two actions must happen simultaneously: sustained military support for Ukraine and a coordinated sanctions regime designed to disable Russia’s war economy at its core.

Precision strikes can destroy factories, and effective sanctions can prevent them from being rebuilt. Together, they form the only path to peace through strength, not through negotiation under never-ending fire.

Yet as of today, nearly half of Russia’s defense-industrial enterprises remain unsanctioned. The United States, the EU, and the U.K. together have designated fewer than a quarter of the 1,700 companies identified as part of Russia’s war machine. This failure is not due to a lack of capacity, but a lack of coordination.

Ukraine already holds the most complete and verified data on Russia’s defense-industrial base: names, subsidiaries, trade routes, and supply chains. Integrating this intelligence into Western sanctions policy would make the system both comprehensive and enforceable.

A sanctions architecture built with Ukraine, not just for it, would finally close the gaps Moscow continues to exploit.

Editor’s note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent.