Carol of the Bells: the song that made the world speak about Ukraine

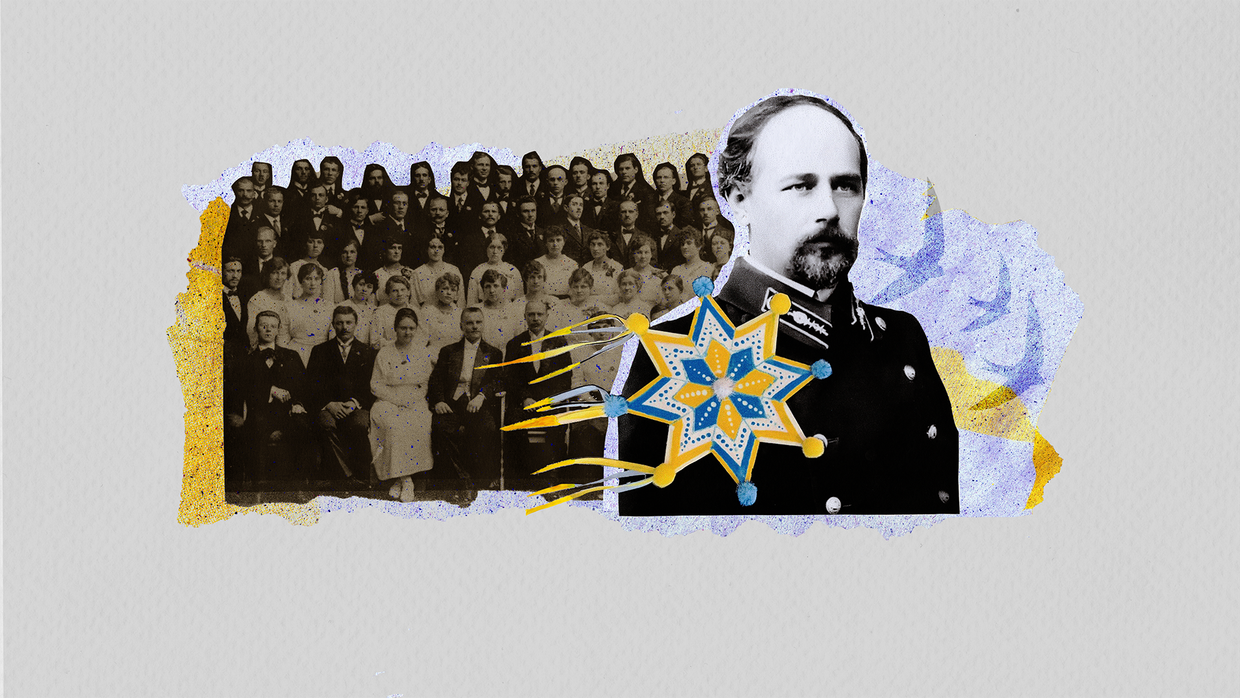

The Ukrainian Republican Capella with conductor Oleksandr Koshyts (C) in Prague, then-Czechoslovakia, in 1919. (Central State Archives of Higher Authorities and Administration of Ukraine)

Mariana Hirniak

Journalist

About the author: Mariana Hirniak is a journalist and public speaker on Ukrainian culture and history.

In early 1919, when Ukraine's pleas for recognition were falling on largely deaf ears, it dispatched not only diplomats to Europe, but also a choir.

Led by conductor Oleksandr Koshyts, the Ukrainian Republican Capella became an unexpected yet powerful instrument of cultural diplomacy. Its greatest triumph was Shchedryk, arranged by composer Mykola Leontovych — a song that would later cross the ocean and reemerge as the world-famous Carol of the Bells.

Today, it is nearly impossible to imagine Christmas without its unmistakable melody.

This journey was no accident. It was made possible by three figures whose visions converged at a decisive historical moment: Symon Petliura, head of the highest governing body of the restored Ukrainian state; Mykola Leontovych, the composer who created the choral arrangement of Shchedryk; and Oleksandr Koshyts, a choral conductor and one of the founders of the Ukrainian Republican Capella.

Following the proclamation of the Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) in 1917, international recognition became critically important.

The timing could hardly have been more consequential. The Paris Peace Conference was about to begin, bringing together the powers that would redraw the map of postwar Europe.

Petliura clearly recognized the power of culture as a tool of statecraft. To secure recognition for the UPR, a diplomatic delegation headed by Hryhorii Sydorenko was dispatched to Paris. Alongside it, however, another delegation set out — unofficial, cultural, and no less consequential. It was led by Koshyts.

The mission of the Capella was clear: to present Ukraine to the world as a distinct nation with its own refined, original culture, clearly separate from that of Russia. In effect, Petliura authorized the first large-scale project of Ukrainian cultural diplomacy in history.

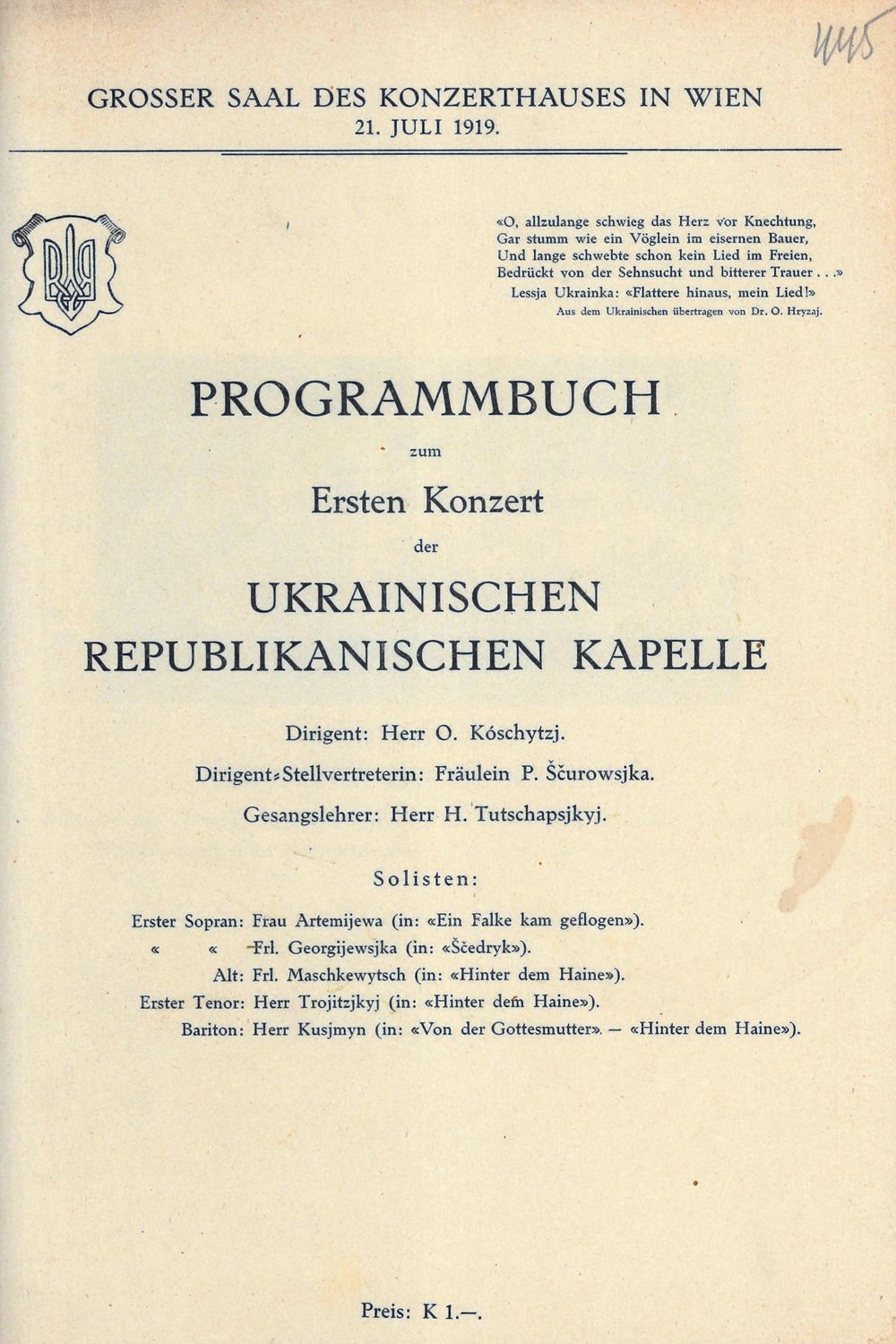

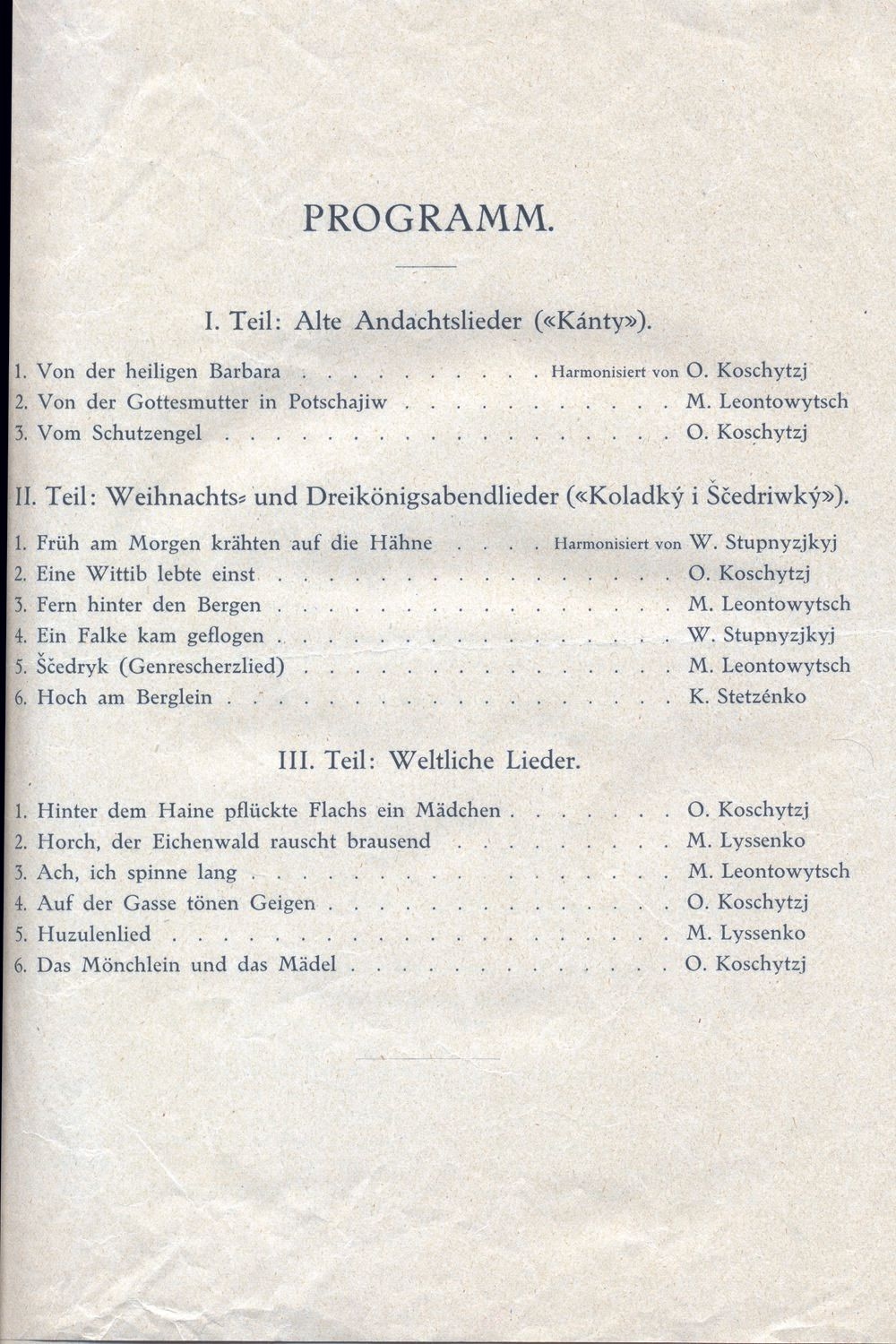

Between May and October 1919, the choir led by Oleksandr Koshyts gave nearly forty concerts across Europe.

Cities like Prague, Brno, Vienna, Baden, Geneva, Bern, Lausanne, Zurich, and Basel all welcomed what became Ukraine’s musical debut on the international stage. Receptions were held in the choir’s honor, attended by the local press and intellectuals.

Audiences often demanded an encore of Leontovych's Shchedryk, a piece the composer had refined over nearly two decades — from its first version in 1901 to the final arrangement in 1919.

"The Ukrainian choir has embarked on a truly triumphant tour," reported Geneva's La Patrie Suisse. "The Ukrainian Republic seeks to restore its independence and has therefore decided to show the world that it truly exists. "I sing, therefore I exist," it declares, and it sings magnificently."

The genius of Shchedryk was neatly captured by Czech musicologist Zdenek Nejedly: "Gentlemen modernists, who need twenty lines of music to express a simple idea — try doing it in four, as Ukrainian composers do!"

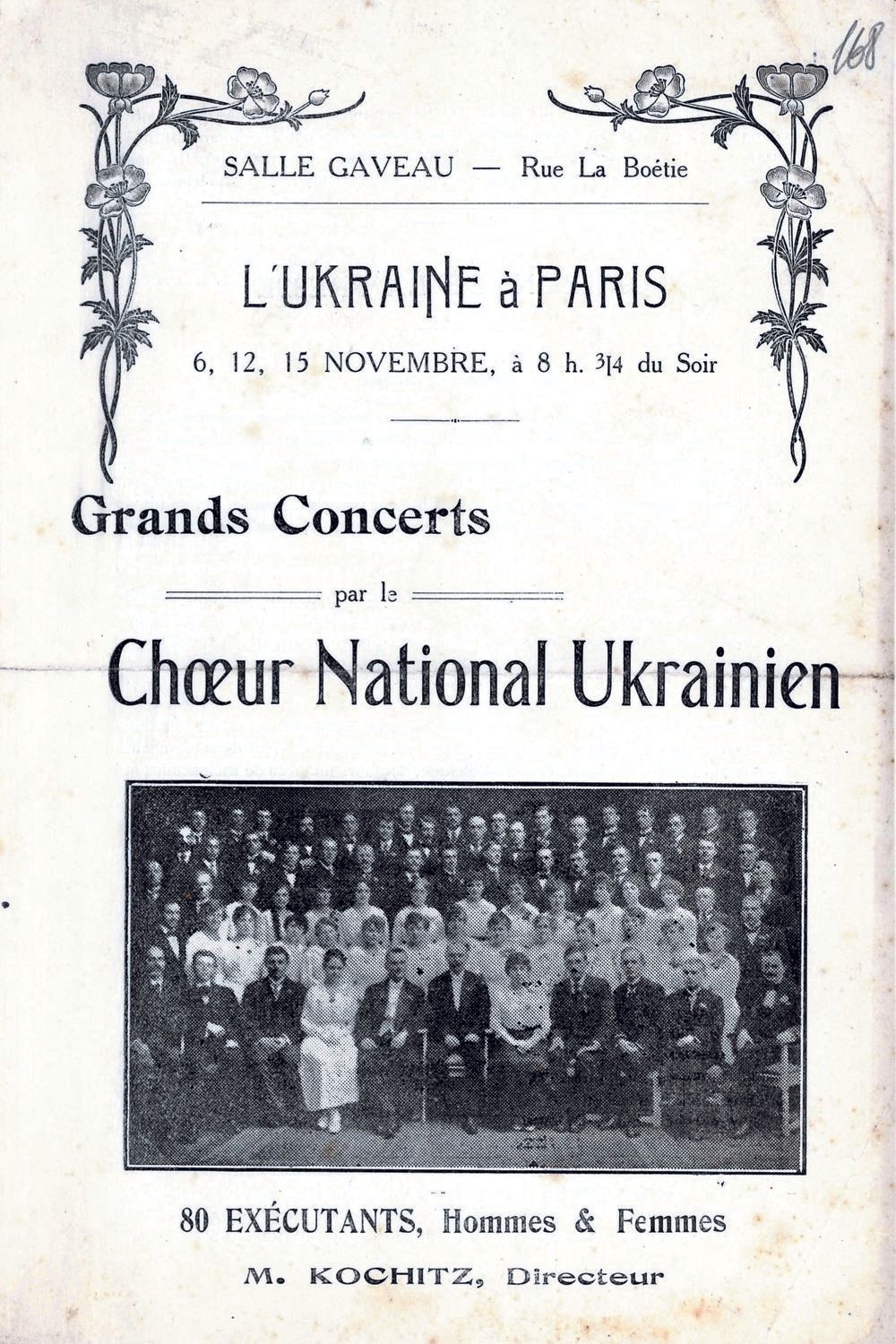

Yet the choir's ultimate destination was Paris. By a special decree, the Ukrainian government sent them to convince the leaders of the Entente that Ukraine was real.

The Paris premiere was a triumph.

Audiences once again demanded Shchedryk. Charles Seignobos, a Sorbonne professor, wrote an open letter to Koshyts in France et Ukraine: "Dear Sir, your singers have exceeded all my expectations… I have not felt anything like this since I heard Wagner in Munich. No form of propaganda could be more effective in securing recognition for the Ukrainian nation."

Not everything went smoothly, though, "Russian colleagues" were ready to sabotage.

"They were clearly planning a scandal," Koshyts recalled. "During our anthem, there was supposed to be shouting and whistling. Then a speaker was to stand up and tell the audience to leave the hall, claiming the concert was being given by Russian separatists, enemies of the 'united and indivisible,' and therefore enemies of France as well."

Yet the attempt to silence the performance ultimately failed. French police intervened, and public backing from the respected journalist Jean Pelissier helped ensure that the concert went ahead.

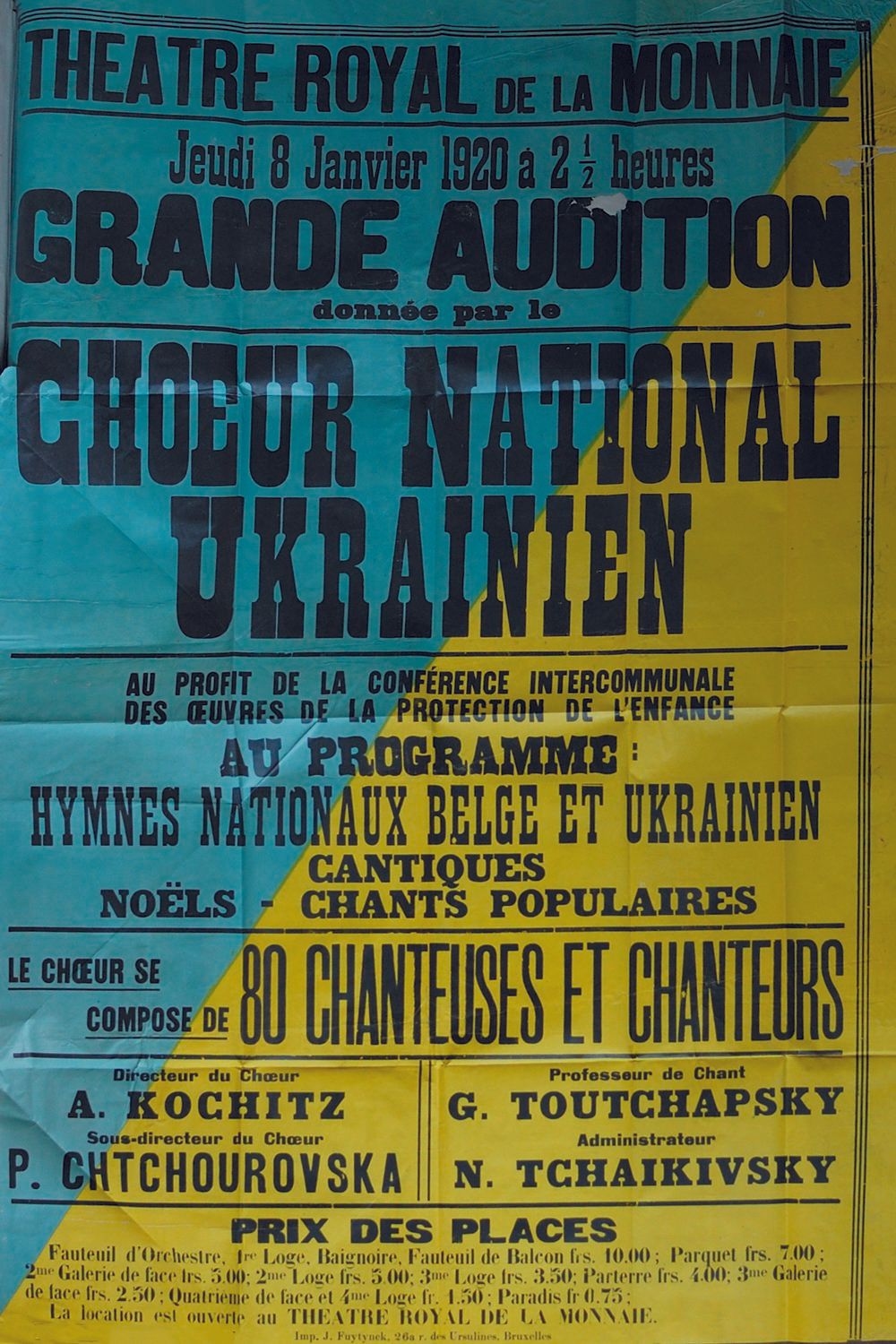

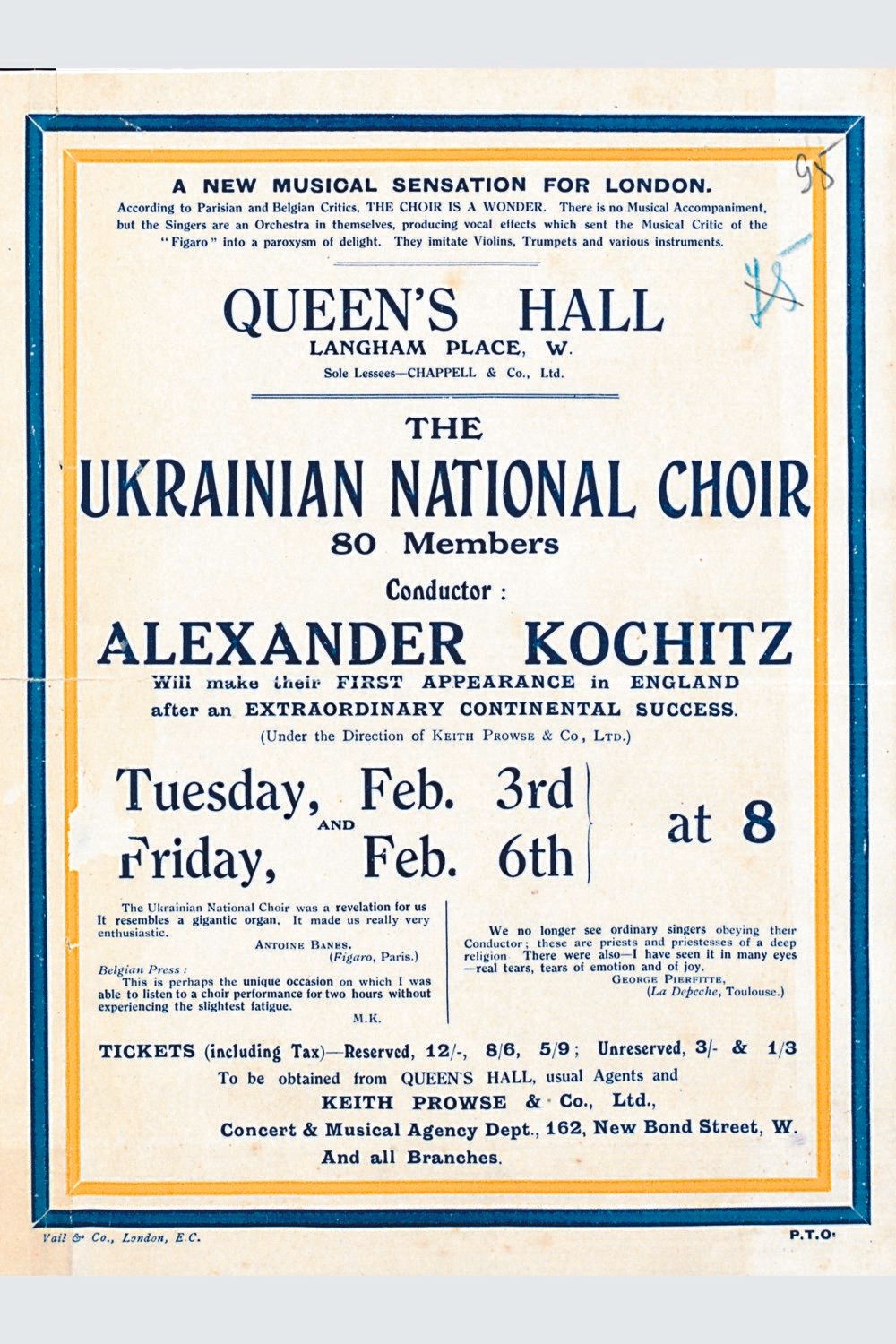

After concluding their tour in France, the choir continued to perform to great acclaim in Belgium, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Germany, Poland, and Spain. Some of the singers even reached Africa, performing in Algeria and Tunisia.

Having failed to secure international recognition for Ukraine in Europe, the choir left the continent for good in September 1922 and moved to the United States.

Just a few months later, on the territories of Ukraine, Belarus, Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan occupied by Russia, the Bolsheviks proclaimed the creation of a new empire — the Soviet Union.

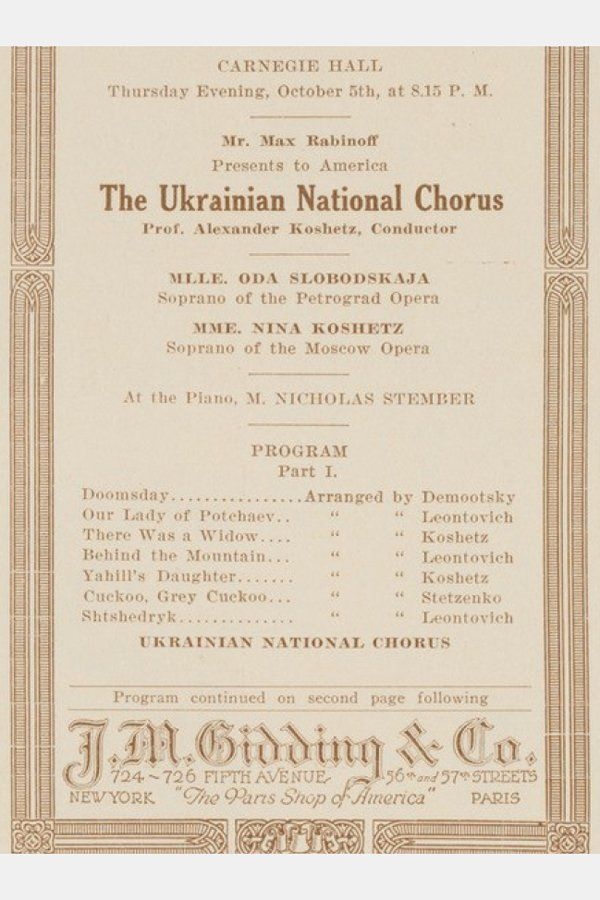

The U.S. tour was organized by the renowned American impresario Max Rabinov. "I heard the Ukrainian National Choir perform in five different European countries," he told the Washington Times, "and each time they received ovations like few I have ever seen. I decided: America must know this extraordinary art."

Finally, the day of the premiere arrived. On Oct. 5, 1922, thousands of eager listeners filled New York's most prestigious concert hall — Carnegie Hall — to experience Ukrainian singing: famous American musicians, politicians, members of the press, and a large Ukrainian community, who had been following their compatriots' European tour since 1919 through news coverage and reviews.

Over the next several days, New York music critics competed to express their admiration, celebrating the choir's remarkable performances.

Continued Touring in America

"They have presented our country not only with the finest singing we have ever heard, but also placed Ukraine on the artistic map of the world." American playwright Clay Green wrote in the San Francisco Journal on Feb. 1, 1924.

After their New York premiere, the choir continued touring in Chicago, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, St. Louis, and more than fifty other major cities across the United States. The choir performed not only in the most prestigious concert halls but also in the grand auditoriums of renowned American universities, including Yale and Princeton.

Between 1923 and 1924, the Ukrainian choir performed in 115 cities across 36 U.S. states, as well as in Brazil, Canada, Mexico, Argentina, Uruguay, and Cuba. The singers even reached the island nation of Trinidad and Tobago.

Everywhere they went, they earned fame and recognition for Ukrainian culture. Shchedryk remained the highlight of every concert.

During this period, over 1,300 reviews appeared in the global press in 12 languages, highlighting Ukraine and its art. The choir also received hundreds of letters from foreign artists and politicians expressing support for Ukraine's cultural and political identity.

Although Shchedryk achieved immense success in the United States, Mykola Leontovych did not live to see it. Just a few months before the international recognition of his work, he was brutally murdered by the Soviets.

On the night of Jan. 23, 1921, in the village of Markivka, in what was then the Podolia region of Ukraine, Leontovych was shot dead by Afanasiy Hryshchenko, a Bolshevik agent posing as a Chekist (Soviet secret police officer). Hryshchenko had asked to stay the night at Leontovych’s home, claiming to be conducting an anti-banditism operation.

In the morning, he robbed the house and shot the composer.

The modern Russian–Ukrainian war is not the first of its kind.

For centuries, Russia has sought to destroy Ukrainians as a nation to erase Ukrainian national identity, culture, and history. Destruction or appropriation has been its consistent strategy.

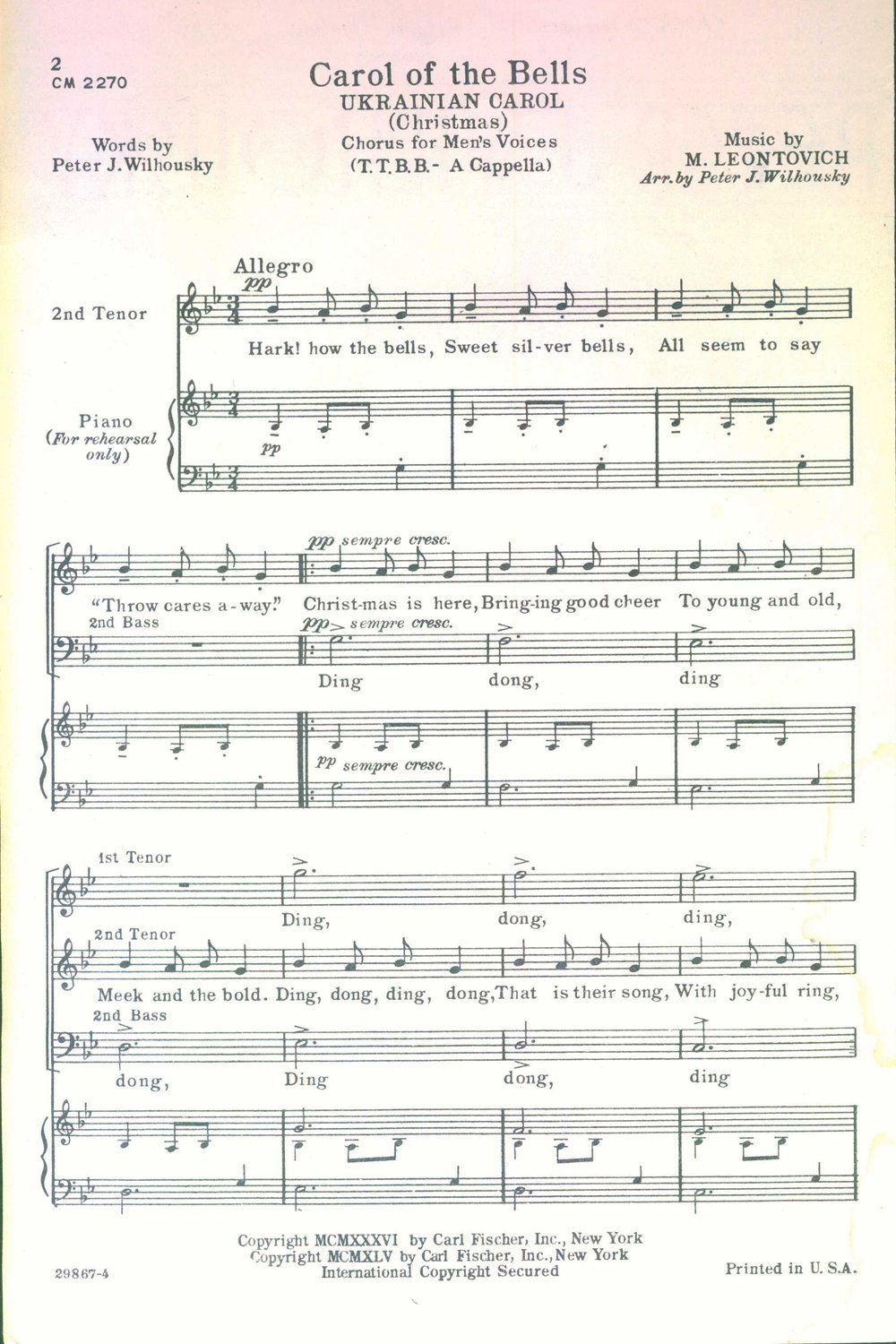

The cultural transformation of the Ukrainian Shchedryk into the American Christmas carol Carol of the Bells would occur a full decade later. On March 30, 1936, at New York's Madison Square Garden, a student choir under the direction of American conductor of Ukrainian descent, Peter Wilhousky, presented Leontovych's arrangement with English lyrics to a gathering of music teachers from across the United States — an audience of 15,000.

In that moment, the American version of the world-famous Shchedryk — the carol Carol of the Bells — was born on the international stage.

Today, Mykola Leontovych's song continues to live on and inspire. Every Christmas, new arrangements of Carol of the Bells fill homes and concert halls around the world.

Shchedryk is not just music, it is a story of resistance. Its composer was murdered, its Paris premiere nearly sabotaged by Russian agents, and today, amid a war that seeks to erase Ukrainian culture, Shchedryk is still played around the world.

To listen is to remember. To perform it is to resist.

Editor’s note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent.