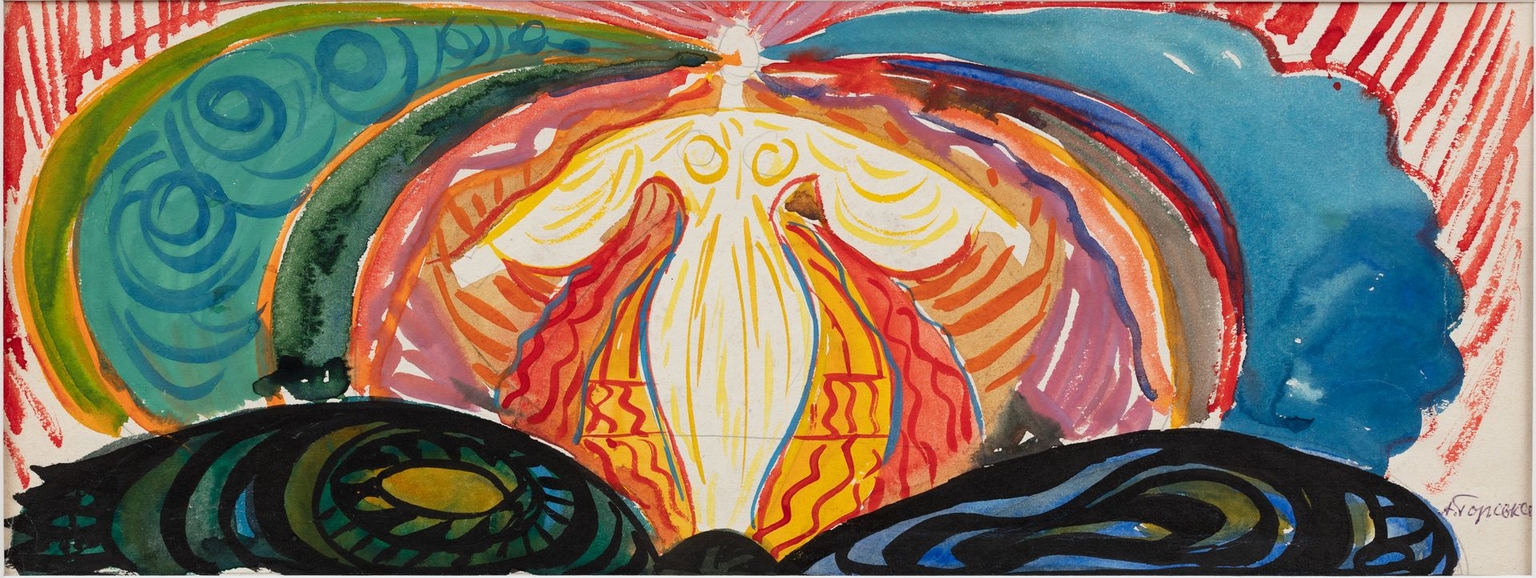

Alla Horska, Ukrainian artist and Soviet dissident of the 1960s Sixtiers movement who was murdered in 1970, likely by the KGB, for her outspoken opposition to Soviet repression and defense of Ukrainian culture. (Anastasiia Starko / The Kyiv Independent)

Editor's Note: This story was originally published in The Kyiv Independent's first-ever print edition, titled "The Power Within." You can order a copy in our e-store.

Carrying a portrait of Ukrainian artist Alla Horska at her funeral, poet Vasyl Stus, who would himself perish in a Russian labor camp 15 years later, did not shy away from calling her death a murder.

On that mournful day, when it fell to Stus to speak, he delivered a poem written in Horska’s memory. Its stark opening line — “Today it’s you. And tomorrow, it’ll be me” — resounded as a grim testament to the plight of dissidents in Soviet Ukraine.

Horska was found dead at 41 in her father-in-law’s basement on Nov. 28, 1970, her skull shattered by a hammer. The following day, her father-in-law was found dead on the train tracks. Soviet authorities ruled it a murder-suicide and closed the case within a month.

To those who knew Horska, however, the official story was little more than a facade. They knew that her unflinching defiance of Soviet doctrines and her commitment to Ukraine had made her a target of the KGB.

Today, Horska’s life is a lasting symbol of the resistance against Russia’s centuries-long campaign to destroy Ukrainian culture. The words “The greatest heresy is to be a Ukrainian in Ukraine,” which she penned in her diary, encapsulate the struggles she and countless others faced in daring to preserve their national identity.

Death destined early

Horska was skeptical of art devoid of cultural roots, human connection, or national identi-

ty. She once criticized Pablo Picasso’s work as embodying “the global bourgeoisie’s worldview,”

contrasting it with Mexican folk art, which she believed “represents its people.”

“I work so that there is contemporary Ukrainian art which represents its people,” Horska wrote in a 1965 letter to fellow artist Opanas Zalyvakha.

Horska’s mosaics stand out as some of her most significant contributions to Ukrainian art,

not only for their innovative technique but also for their embrace of Ukrainian folk motifs that rebuked the constraints of socialist realism.

"Alla cannot cease to exist!"

In the wake of World War II, as the Soviet Union sought to establish itself as a major power on the global stage, it promoted art that glorified the state’s industrial might. Mosaics — valued for their durability and visual impact — became a favored medium for public spaces that advanced socialist ideology. For many artists, taking on these public works offered both a good source of income and some relative freedom to navigate the pressures of state-sponsored art.

Traveling across Ukraine, most notably to Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in the east, Horska and a collective of fellow artists pieced together vibrant mosaics that transcended the limitations of Socialist realism and found ways to incorporate aspects of Ukrainian culture in their work, sometimes subtle, other times overt.

The 1967 mosaic “Blooming Ukraine,” created in now Russian-occupied Mariupol, depicts a woman with outstretched arms clad in traditional Ukrainian folk attire. Her figure radiates with beams of light that elevate her to a quasi-divine status, symbolizing strength and the possibility of transcendence. Floral motifs interwoven into the composition evoke growth, vitality, and renewal, subtly alluding to the enduring spirit of Ukrainian culture. The mosaic’s serene imagery masks its abrupt defiance of Soviet rule, a quiet yet unyielding reminder that Ukrainian identity cannot be suppressed indefinitely.

Culture, history, and politics were inseparable for Horska’s generation, known collectively as the Sixtiers. In 1962, Horska, along with theater director Les Taniuk and poet Vasyl Symonenko— who would later die at 28 after a brutal police beating — discovered a mass grave outside the village of Bykivnia in Kyiv Oblast. The site contained victims of the Great Terror, a period during the 1930s when Joseph Stalin’s regime consolidated power by executing thousands through political purges, genocide, and ethnic cleansing. Estimates suggest that across the Soviet Union, the Great Terror claimed the lives of anywhere between 700,000 to 1.2 million people.

In his diary, Taniuk described how trees had started to grow through human skeletons and how sand samples would reveal not only traces of blood but also the use of lime to accelerate the bodies’ decomposition. It was during a conversation about more famous mass graves that locals disclosed their village’s hidden truth to the young trio.

“On our way back, we walked in silence, slowly starting to come to our senses. If we hadn’t had that swig (of alcohol) in the forest, I don’t know what would have happened to us. Alla started to curse like a sailor, and I understood her. Then, she fell silent,” Taniuk wrote.

Throughout her life, Horska was committed to helping and supporting Ukrainian political prisoners, writing letters of encouragement to them while they were still in custody and offering both financial assistance and temporary refuge upon their release. Repeatedly summoned for questioning by the KGB, Horska was always resolute in her silence, never betraying anyone.

As Horska’s granddaughter Olena Zaretska wrote in a recent monograph published in the spring of 2024 to coincide with a major art exhibition in Kyiv of Horska’s work, Horska was “fearless but not reckless,” possessing an acute instinct for identifying the Soviet regime’s agents seeking to infiltrate and sabotage the ranks of Ukrainian dissidents.

There was an obvious commonality among those who believed in a more democratic future for Ukraine and freedom of expression. To quote Stus in one of his many poems dedicated to Horska following her murder, the Sixtiers embodied the ethos that “Death was destined early for us all, / for the guelder rose is just as fierce, / just as tart, as in our veins.”

More than a mere tribute

Artists like Horska posed a threat to the Soviets because they defied the regime’s efforts to portray the people of the Soviet Union as a single, homogenized entity united by communism. To achieve this, the Soviet regime sought to rewrite, distort, or suppress historical narratives that did not align with its propaganda, leaving individuals disconnected from their cultural roots and collective national memory.

That’s why, for Horska and her fellow Sixtiers, understanding and preserving Ukrainian history across their professions became a sort of shield, a source of strength, and a pathway to cementing their identity in the face of relentless ideological control.

As Horska wrote to Zalyvakha, “History is not merely a collection of facts — it is a process of development and progress. Art, similarly, is not just an assembly of components but unity in motion.”

Horska’s paintings in the 1960s could primarily be characterized as an extension of the art championed by the early 20th-century Ukrainian avant-garde; they became increasingly bolder and more political. Building upon the innovations of European movements like cubism, futurism, and constructivism, as well as elements of Socialist realism, Horska blended these artistic techniques with centuries-old Ukrainian folk motifs, emphasizing Ukraine's cultural heritage.

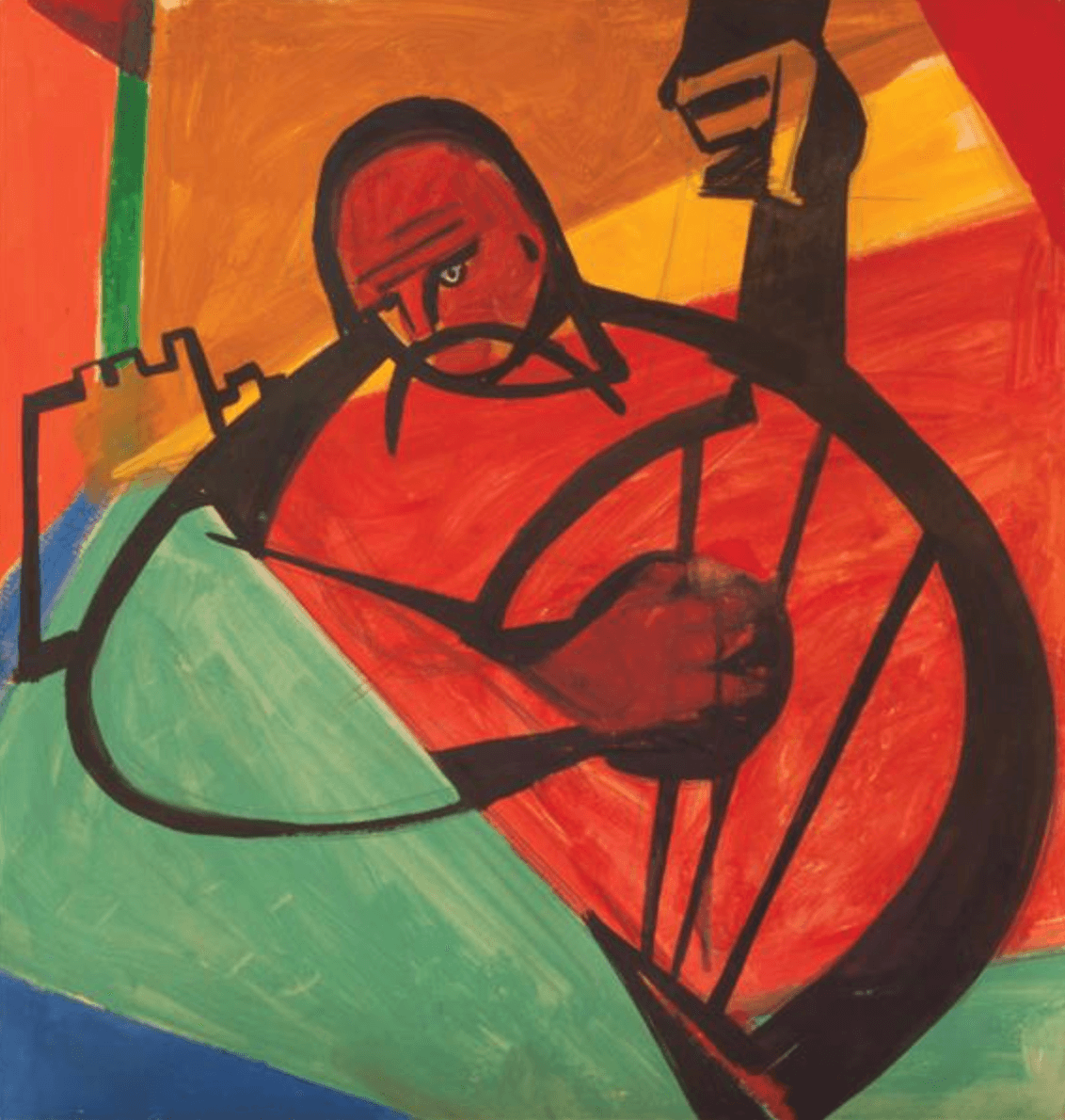

One example is her depiction of Cossack Mamay, a Ukrainian folk hero. His popularity in storytelling grew after Russian Empress Catherine II dismantled the Zaporizhzhian Sich — a semi-autonomous proto-state of Cossacks in Ukraine — in the late 18th century. Once a stronghold of Cossack society, the Sich’s fall marked the decline of the Cossack warrior elite as their lands were absorbed into the Russian Empire.

Yet, the Cossacks lived on in Ukrainian art and literature as symbols of strength and resilience. Cossack Mamay, portrayed as a brave warrior, talented musician, and thoughtful philosopher, captures the essence of the Cossack spirit: courage, wisdom, charm, and strength.

The composition of her 1963 painting plays with angular geometry and fluid lines, distorting Mamay's figure into an almost cubist synthesis. Horska’s depiction emphasizes the dynamic interplay between Cossack Mamay, his kobza, and the surrounding environment. The contrasting fields of color — blazing oranges, deep reds, and verdant greens — envelop Cossack Mamay, creating a pulsating visual rhythm that mirrors the cadence of his music. Thick black contour outlines his figure, adding both weight and grounding, inviting spectators to contemplate the interplay between heritage and modernity, tradition, and abstraction.

Horska's visual dialogues with Ukrainian history also include her depictions of 19th-century poet Taras Shevchenko, some of which were destroyed by Soviet authorities for being deemed "counterrevolutionary,” or antithetical to the Communist party's ideology.

The composition of her 1963 painting plays with angular geometry and fluid lines. Horska’s depiction emphasizes the dynamic interplay between Cossack Mamay, his “kobza,” a Ukrainian folk music instrument, and the surrounding environment. The contrasting fields of color — blazing oranges, deep reds, and verdant greens — envelop Cossack Mamay, creating a pulsating visual rhythm that mirrors the cadence of his music. Thick black contour outlines his figure, adding both weight and grounding, inviting spectators to contemplate the interplay between heritage and modernity, tradition and abstraction.

Horska’s visual dialogues with Ukrainian history also include her depictions of 19th-century poet Taras Shevchenko, some of which were destroyed by Soviet authorities for being deemed “counterrevolutionary,” or antithetical to the Communist Party’s ideology.

The stained-glass panel “Shevchenko. Mother” was a collaborative project by Horska and several of her colleagues. It depicts Shevchenko with one arm embracing a maternal figure symbolizing Ukraine, while his other hand proudly raises his iconic poetry collection, “Kobzar,” meaning “a kobza player” in Ukrainian. Surrounding the figures are Shevchenko’s stirring words: “I’ll raise them up, these mute and lowly slaves. And to stand guard beside them I’ll place my word!” This imagery encapsulates Shevchenko’s legacy as a defender of his people and culture through the power of his art, as “the father of the nation.”

Born a serf, Shevchenko overcame a life of bondage thanks to his extraordinary artistic talent, which inspired admirers to secure his freedom. His works in art and literature captured the hardships endured by the Ukrainian people under Russian imperial rule. In 1847, Shevchenko was arrested and exiled to military service in Kazakhstan, becoming a target of Tsar Nicholas I’s anger. Shevchenko’s poetry, a fierce critique of imperial oppression, led to a harsh decree: Shevchenko was forbidden to write or draw. Yet, despite this ban, he managed to continue to make art.

Created for Kyiv’s Taras Shevchenko National University, Horska’s “Shevchenko. Mother” became a casualty of Soviet censorship. Pressured by authorities, the university rector himself is said to have smashed the panel with a hammer, declaring it incompatible with Soviet “values.” Unfazed, Horska wrote an angry letter to the USSR’s Union of Artists, declaring that she and her colleagues had “sought to capture the love and hatred, strength and energy of the great Kobzar — his devotion to his people and his monumental historical feat: his selfless, courageous stand in their defense.

The untimely deaths of Horska and Stus left irreplaceable voids in Ukrainian art and literature. The lives of these artists, filled with promise for Ukraine and the world, were stolen by Russia. For centuries, Russia has spilled the blood of Ukrainian artists. The tragic life stories of Horska, Stus, and countless other Ukrainian artists killed by Russia could form the contents of an entire book. Yet, amid this grief, their loved ones have repeatedly found hope in the legacy these artists left behind. “I know that Alla cannot cease to exist!” literary critic Yevhen Sverstiuk said at her funeral. “She lives on in everything — a person who personally needed nothing cannot vanish into oblivion. Alla is here, she is unwaveringly present where there is sorrow, misfortune…wherever strong shoulders (to lean on) are needed.”

As Russia continues to target Ukraine’s cultural heritage — like the destruction of several of Horska’s mosaics in Mariupol at the start of the full-scale war — we are reminded that remembrance is more than a mere tribute; it is an enduring source of strength, crucial to the survival of one’s country and its people.