Youth exodus — Ukraine's young people are increasingly quitting their jobs to go abroad

Refugees from Ukraine queue as they wait for transport at the Medyka border crossing after crossing the Ukrainian-Polish border in southeastern Poland on March 23, 2022. (Angelos Tzortzinis / AFP / Getty Images)

Young people are quitting their jobs en masse following Kyiv’s decision to allow men aged 18-22 to leave Ukraine, according to a new survey from Robota.ua, a Ukrainian recruitment platform.

Ukraine had banned men aged 18-60 from leaving the country at the start of Russia's full-scale invasion in 2022, unless they had an exemption, like fathers with three or more children, and disabled men and their carers.

That changed in August 2025 when the government partially lifted the ban for 18-22-year-olds — a move that left many in Ukraine confused as the country grappled with manpower and labor shortages. Officials said the change was intended to encourage young men living abroad to return for visits and to give men in the country access to international education opportunities.

There are no exact figures on how many 18-22 year old men have left since the decision, as data from Ukraine's border guard service does not include age or sex. But departures reached a three-year high in August, the highest level since March 2022, according to border guard data.

Businesses say they're feeling the impact of the rule change, with 71% of companies surveyed by Robota.ua reporting an increase in young employees resigning since the August decision. Half of the respondents said many 18-22-year-old employees were leaving because they wanted to move abroad.

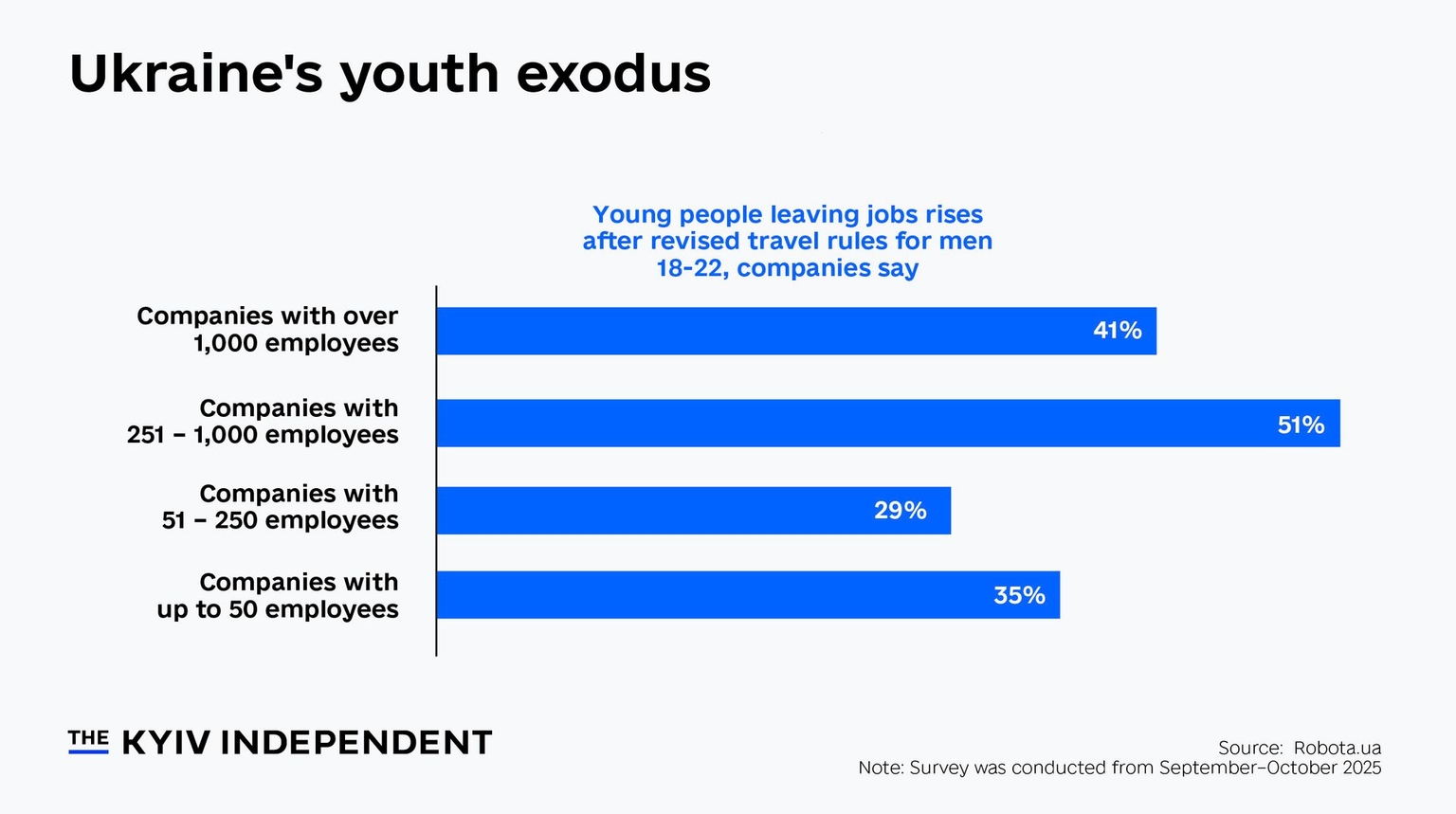

Of the companies surveyed, 38% stated that the resignations were "significant." Bigger companies are seeing more young people leaving, with 41% of businesses with over 1,000 employees noting significant departures.

With flight abroad and nearly a million men fighting, Ukraine is already struggling with a crippling workforce deficit, particularly in male-dominated industries, like metallurgy. While efforts have been made to dampen the impact of the brain drain, including retraining women to take on typically male jobs, Ukraine has yet to find a solution capable of meaningfully filling the gap.

At the same time, the travel ban left many young men feeling stifled in Ukraine while their female relatives and friends started new lives abroad. The uncertainty of Russia’s invasion and the rollercoaster of peace talks this year have left many feeling pessimistic about future career growth within the war-torn country.

With young people increasingly going abroad, the companies also said attracting fresh young employees is becoming more challenging, with 55% admitting it is now "significantly more difficult."

It’s not just men moving out of Ukraine. ArcelorMittal Kryvyi Rih, a steel plant, told the Kyiv Independent that when young men leave, they often take their girlfriends or wives with them, some of whom also work at the plant.

The government is working on a roadmap to encourage returnees, like creating opportunities that match the skills Ukrainians acquired abroad, Volodymyr Landa, head of Investment Screening at the Economic Security Council of Ukraine, told the Kyiv Independent.

But long term, it’s going to be harder to convince young people to come back rather than encouraging them to stay, he added.

"Every person that left is a loss," said Landa.

European countries are noticing more young men arriving. In Germany, 1,000 men are registering in the country every week, up from 100 prior to August, Deutsche Welle reported last month.

Businesses are feeling the squeeze. Of those surveyed by Robota.ua, 34% said it significantly affects their operations, 42% said it somewhat affects their businesses, and 20% said they felt no impact.

Among the hardest hit sectors are sales and customer service. Even the IT industry, which offers high salaries and skilled jobs, was the third most impacted sector.

The increased departures come on top of long-term labor shortages that are hindering the productivity of Ukrainian companies, with some looking to migrants to bolster their workforce. According to the European Business Association in Ukraine, 71% of companies surveyed last year were suffering a serious personnel shortage.

To plug the outflow, employers are hiring older candidates, transferring responsibilities to other employees, increasing salaries, and automating responsibilities. Respondents said they could also offer flexible work schedules to combine with university studies, or save jobs for those who leave, should they decide to return.

The majority believe that the state should also step in to help, for example, by offering tax breaks or internship programs. With many young men fearing being recruited to the military amid the never-ending bloodshed, other options could include increasing the number of exemptions from the army or guaranteeing exemptions after they reach 25 years old, the mobilization age.

For many businesses, the only way to really stop young talent from leaving Ukraine is an end to Russian aggression.

All other attempts are "futile," Robota.ua said.

A note from the author:

Hi, this is Dominic. Thank you for reading this story. Ukraine's demographic and labor crisis is a story that we will be following for years to come. It's a question on the minds of many here in Kyiv. But so far, no one has found the solution. To keep up with stories like this, please sign up as a member. It costs the same as a cup of coffee. Thank you!