The new Kyiv Independent’s documentary “Torture Culture” presents an in-depth investigation into the systematic torture of Ukrainian civilians in Russian captivity. Men and women who were detained by Russian forces in Ukraine at various locations and held in multiple facilities in Ukraine and in Russia itself recount in detailed interviews all they had to survive: beatings, electrocution, sexual violence, and psychological pressure.

Our team traces the history of Russian torture across different times and places, including in Chechnya (a Chechen survivor also details his experience in Russian detention in the documentary). We also examine testimonies about widespread torture in the Gulag and in Western Ukraine in 1939-41.

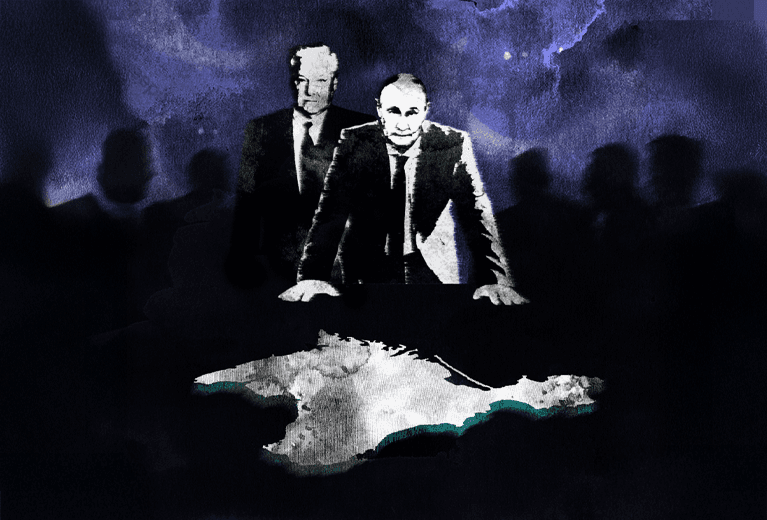

The documentary establishes patterns and similarities in Russian torture practices against civilians that appear to transcend time and territory. There seems to be a system of Russian torture, passed from one generation to another, that is deeply ingrained in Russian culture.

OPINION

Torturing prisoners is not merely a war crime that Russians perpetrate, it's part of Russian culture. Susan Sontag's 20-year-old essays may help us understand it.

In the Kyiv Independent's latest investigative documentary “Torture Culture,” we examine the sufferings that Russians systematically inflict on their Ukrainian prisoners — all the beatings, electrocutions, mutilations, sexual abuse, psychological violence — not only as a war crime but also a cultural phenomenon, something that Russians do decade after decade, whenever and wherever the opportunity presents itself.

From Western Ukraine in 1939-1941 to the Gulag system, from Chechnya to today's occupied territories, torture resurfaces again and again.

As it usually happens, some parts of our work on the documentary did not make it into the final cut. For example, during the interview with the Chechen human rights defender Akhmed Gisaev (who himself survived Russian detention and extensive torture in 2003) we discussed how the intent to instil fear in civilians with torture (and with spreading information about it among the population) in the occupied territory alludes to the Russian popular “matrimonial” proverb, “If she fears you it means she respects you.”

An important point in the documentary is that the perpetrators of torture most often seemed to thoroughly enjoy the process.

Several survivors talked about it in their interviews. But there's also a seemingly small detail that we left out from the film — and which, upon reflection, is quite telling: according to all of our interviewees, Russian torturers liked to record the beatings, electrocutions, waterboardings, and other abuses and humiliations on their smartphones.

More investigations