Rajan Menon: 'Putin has lost Ukraine'

Editor's Note: The Kyiv Independent is exclusively re-publishing an interview with Rajan Menon prepared by Forum for Ukrainian Studies, a research publication for experts, practitioners, and academics to discuss, explore, reflect upon, develop, and transform international understanding of contemporary affairs in Ukraine. This platform is run by the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) of the University of Alberta (Edmonton, Canada).

Rajan Menon is the Anne and Bernard Spitzer Chair in Political Science Emeritus at the City College of New York. He is a senior research scholar at the Arnold A. Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University.

CIUS: This February marks ten years since the start of the Russo-Ukrainian war and two years since the start of its full-scale stage. Has this war made you fundamentally reconsider any notions or theoretical frameworks?

Rajan Menon: I’ve long believed that the U.S. has been unwilling to allow any external power to establish itself in our hemisphere—the Western Hemisphere—since almost the founding of the country. But Russia has a certain proprietorial vision of the former Soviet states, especially Ukraine. I think that for historical, strategic, and cultural reasons, it’s very difficult for Russian nationalists—and Putin is one—to conceive of Ukraine as an independent country. So I’ve never doubted that Russia wants to keep Ukraine within its sphere.

In 2008, when NATO opened its door in principle for Ukraine to join the alliance, tensions about where Ukraine would “belong” — to the West, the East, or Russia — became much more controversial. At the time, I was not a proponent of NATO enlargement, because I understood that when alliances intrude on what great powers think, rightly or wrongly, is their sphere of influence, there will be some backlash.

Where my thinking has changed with my fellow realists is on the following point. On Feb. 24, 2022, when Putin invaded Ukraine, there was no evidence that Ukraine was any closer to joining NATO in 2022 than in 2008. Thus, I simply do not find the argument that he had to invade Ukraine to stop it from joining NATO to be credible.

I think that NATO could not have mustered the unanimity required to admit Ukraine. NATO did a disservice to Ukraine by promising that the door was open and they would be admitted and then keeping them waiting for 14 years. It was not a very smart thing to do. They either should have said yes and moved quickly or just said no and clarified things. My departure from my previous view concerns the question of what triggered the invasion. I do not think it had to do with Ukraine’s prospects for joining NATO.

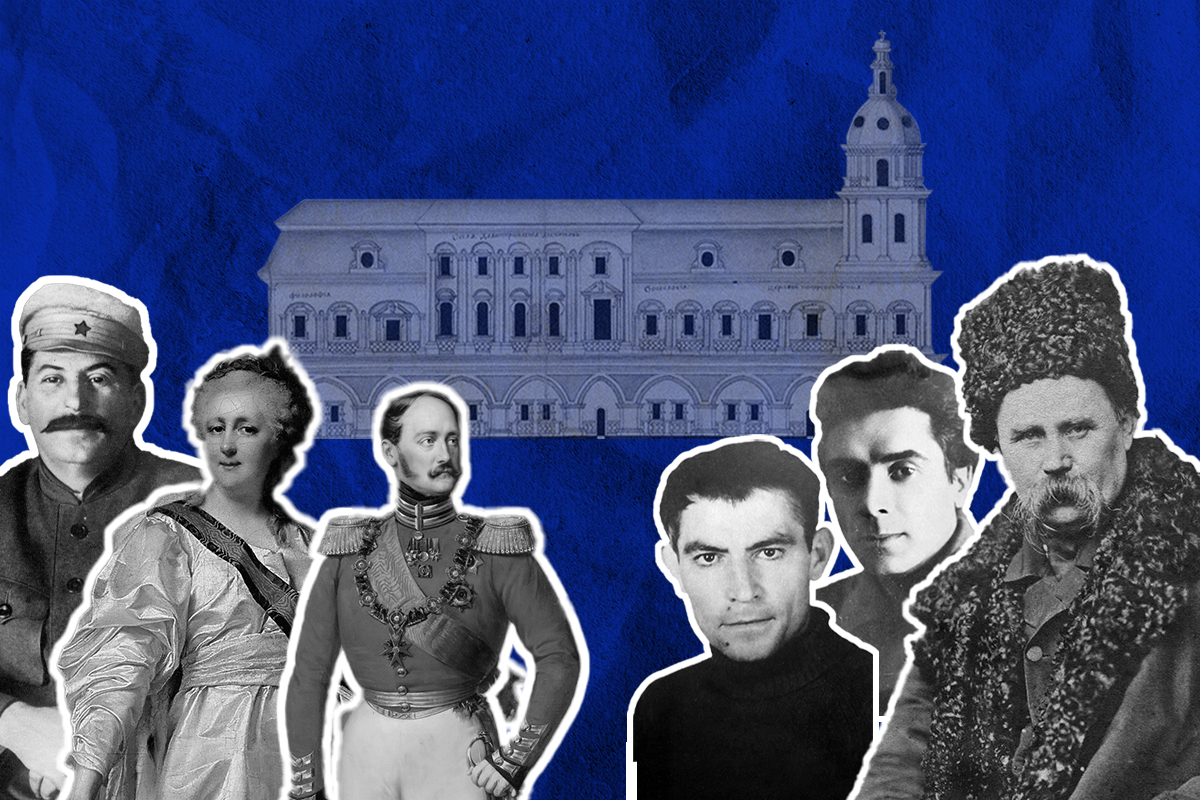

I also have an alternative theory that does not rest on evidence, but let me share it. Putin went into complete isolation during the Covid period. Very few people were able to see him. He demanded that documents be brought to him from the Russian archives. We know that he was reading widely about [the imperial rulers] Catherine II and Peter I. He was maybe thinking about his mortality, about his legacy. I think he wanted one of his legacies to be for Ukraine to be brought back into the Russian sphere. This is a hunch, but it’s the only alternative explanation I can arrive at as to why the full invasion happened when it happened. Frankly, I was stunned. I did not think he would fully invade a sovereign country, but he did, and he expected a quick victory.

CIUS: In one of your essays you called Russia’s war against Ukraine the war of surprises. I’m curious about the part that involves Ukraine. Why was Ukraine’s resistance to Russia’s aggression surprising to many experts in the West, particularly after Ukraine had two popular revolutions?

Menon: It did not surprise me that the Ukrainians would resist a Russian invasion. Generally, when you invade another people’s country, you’re challenging their right to exist, and there will be resistance. What I did not expect was how poor the Russian military preparations were and how hubristic they were in thinking they would march into Kyiv and install someone like Viktor Medvedchuk in place of Zelensky. And I underestimated the success with which Ukraine not only pushed the Russians from the gates of Kyiv by April but also cleared the Russian army from most of the north, including areas as far north as Chernihiv. So, the Ukrainians resisted—and in such a way that the Russian Army was turned back.

This resistance occurred successfully before Western arms started flowing into Ukraine in a major way. The Western assessment, for example from Mark Milley, then chairman of the American Joint Chiefs of Staff, was that Kyiv would be taken in 72 hours. He was not the only one saying this. To be honest with you, I thought the Russians would prevail because they had a massive advantage in everything. That’s why their failure somewhat surprised me. Although I never expected the Ukrainians just to capitulate. I didn’t expect, for example, [the Sudetenland,] Czechoslovakia, in 1938.

CIUS: One of Putin’s miscalculations was that when he started the full-scale invasion, he thought it would be easy to take control of the regions of Ukraine where many people speak Russian. His Federal Security Service spent hundreds of millions to infiltrate those regions with agents and gain local population support. But as we see now, controlling those occupied territories is challenging for him too. News from those regions indicates that resistance and partisan movements within those territories are consistent and growing.

Menon: Just a couple of thoughts on this. Despite the reputation that he’s now gained, Putin is not actually a person who takes big risks. The 2008 war against Georgia was not a risk. The 2015 intervention in Syria was not a risk, because he didn’t put ground troops down. Crimea 2014 was not a risk either —it is geographically close to Russia and Ukraine’s only Russian-majority province (two-thirds of the population and by some counts closer to three-fourths) with thousands of retired Soviet army personnel. I should also add Russia had a naval base on lease from Ukraine there at the time.

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has proved to be a disastrous decision. But from his point of view, it wasn’t a risk, because all the intelligence that Russia had on the ground suggested the Ukrainians would welcome the Russian army, much like the Soviets thought the Afghans would welcome them in 1979. One of the reasons they assembled a small force relative to Ukraine’s size was that they expected a quick victory. I have friends in the Ukrainian military who tell me that when they looked inside Russia’s destroyed tanks and armoured personnel carriers, they found parade uniforms. Rumor had it that a few days before the start of the full-scale invasion, they even called Kyiv’s swanky restaurants to make reservations to celebrate their quick capture of the city. There’s no question that they were shocked at Ukraine’s resistance.

Regarding Russophone Ukraine, this is a highly complex question, and many misunderstandings exist in the West about it. If you look at, for example, the election that Yanukovych won, the election results are pretty clear that the Party of the Regions did much better in the east and south than elsewhere. But the idea that there is a split Ukraine is vastly overplayed.

I’ve been to Ukraine four times since the full-scale invasion began. I just came back last December. I’ve been there many times before. I don’t speak Ukrainian and have never presented myself as a Ukrainian expert. But I do know that I have talked to Ukrainian soldiers on the front lines in the east and in the south who spoke to me in Russian. I thought they were speaking to me in Russian because I don’t know Ukrainian, but then I noticed that they were speaking to each other in Russian, yet fighting the Russian army. This idea that everybody in the east and the south is pro-Russian and waiting to be liberated is a myth, one that Putin believed and wanted us to believe.

And finally, which parts of Ukraine have been devastated the most by the Russian invasion? It’s the very areas that Putin claims he is the savior of! It’s a very strange thing, but I think he fell victim to this notion of being a savior.

I sometimes tell friends, only partly joking, that in a weird way, Putin has been unwittingly, that is, accidentally, one of the main contributors to modern Ukrainian nationalism. He has reformed and reframed a Ukrainian identity that is stronger than before. Let’s assume that the war ends—now, I’m not predicting this, especially because American aid is now in doubt—with Russia retaining some proportion of Ukraine’s territory. Whatever remains of Ukraine, and quite a bit will remain, will irrevocably lean Westward. Young Ukrainians will all learn English or European languages, with their entire outlook toward the West. In that sense, no matter the military outcome of the war, Putin has lost Ukraine. There’s not going to be a Ukraine heading toward Russia. The defining characteristic of Ukrainian nationalism will be opposition to Russia.

Read the full interview here.