Opinion: Facing Ukraine’s south

One of the key insights I’ve gained about myself during this war has been that I held onto preconceived notions not only about foreigners but my fellow Ukrainian citizens. As a filmmaker and writer, I recognize the significance of the optics we rely on to perceive certain things. That's why, since the early years of the war, I’ve extensively traveled to witness everything I can firsthand.

This has led to literary readings in front-line cities, meetings with members of the military and civilians, master classes for teenagers in Avdiivka, and a year of filming in the front-line city of Krasnohorivka in Donetsk Oblast. I’ve also traveled abroad on numerous occasions since the start of the full-scale invasion, being invited as a speaker to cultural events in different countries. Navigating between these parallel realities has sharpened their contrasts and revealed previously unseen details about the world around me.

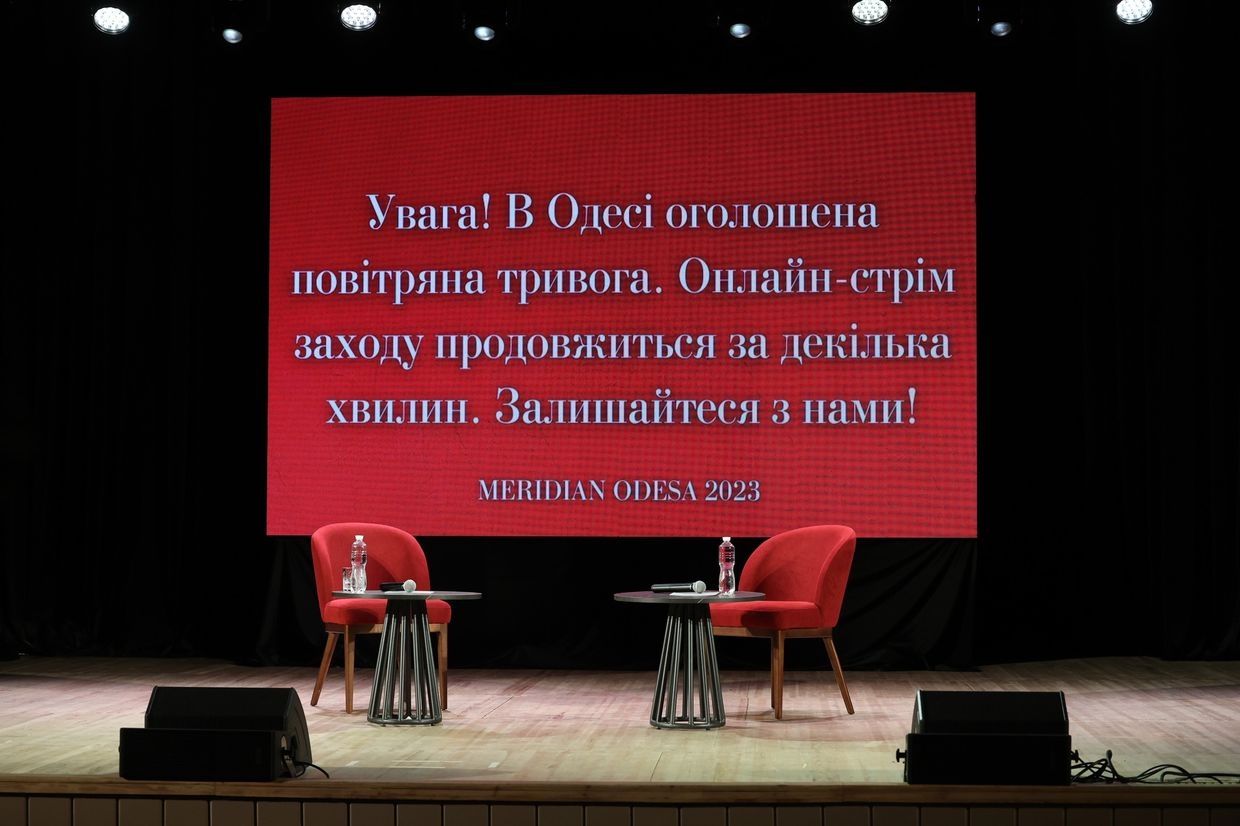

At the beginning of November, I embarked on a literary tour of southern Ukraine that was organized by the Chernivtsi-based publisher Meridian Czernowitz. With the help of USAID, Meridian Czernowitz held a literary festival in Odesa, along with readings in Mykolaiv, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia. A special emphasis was placed on Odesa, where the events were held over three days despite the ongoing risk of Russian attacks.

Russian propaganda has always tried to portray Odesa as an “eternally Russian city.” The struggle for identity in this region has a lengthy history. However, despite the aggressive influence of prolonged Russification campaigns, the local Odesa community striving for Ukrainian culture has always been present and very active. At the same time, there are other residents of the city who, until recently, attended the events of Russian writers and other artists – even during wartime years. These days, that latter dynamic has shifted. I keenly sensed such a change while I was there. The level of interest in Ukrainian culture has only continued to grow in Odesa, especially when Russian missiles and drones target the city.

A packed hall of people wanting to see the immensely popular poet Serhiy Zhadan was no surprise, but the turnout at other events was equally impressive. Halyna Kruk, Peter Pomerantsev, Ivan Malkovych, Taras Prokhasko, Artem Chekh, Andriy Lyubka, and many many more read their poetry and prose and engaged in discussions to the delight of the audience. It continued despite the blare of air raid sirens and temporary disruptions to seek out the nearest bomb shelter.

The echoes of Russia’s war resounded the loudest during the closing event of the festival when Russian ballistic missiles and drones hit the city center. We departed Odesa with heavy hearts: one of the missiles had struck in front of the Fine Arts Museum, inflicting partial damage upon the building. This news overshadowed the fact that the museum was celebrating its 124th anniversary.

Three authors traveled further – Andriy Lyubka, Serhiy Zhadan, and myself. In Kherson, we were joined by the poet and combat medic Yaryna Chornohuz.

Many people long believed that southern Ukraine would never exhibit as much interest in contemporary Ukrainian culture compared to the central and, particularly, the western regions of the country. However, Russia has clearly lost in that arena.

Could I have imagined earlier that hundreds of people would be awaiting us so eagerly there? Many residents departed these front-line cities, which still face the threat of constant attacks. The reality of war permeates everything there. Despite this, the remaining locals cope with a mix of fatalism and humor.

In Mykolaiv, the traces of constant Russian attacks are very pronounced and noticeable. This includes the remains of the Regional State Administration building, which was targeted by a Russian missile attack in March 2022 and claimed the lives of 37 people, including the artist and poet Nadiya Agaphonova, who was a personal acquaintance of mine. But life in Mykolaiv persists, a testament to its resilience. In this context, the sight of a packed 400-seat hall was nothing short of breathtaking. Attendees soaked up poetry and prose for four hours and treated us as if we were rock stars.

Kherson, which was liberated from Russian occupation by the Armed Forces of Ukraine last fall, still faces the threat of Russian attacks on a daily basis. Heightened security protocols demanded increased vigilance during our time there. It was the only city where our event took place as if in secret, held in a bomb shelter during the middle of the day. The venue was brimming with an eclectic mix — civilians, military personnel, medics, volunteers, and war correspondents. In this setting, where people removed their helmets and bulletproof vests to listen to literature, poetry became more than mere verse; it evolved into a clandestine language, a covert bond that united and sustained kindred spirits.

Zaporizhzhia, the final point of our literary tour, was no less impressive. Registration had to be halted two days prior to the event as the hall, originally designed for 300 seats, had attracted an overwhelming 700 registrations. Truth be told, it was one of the most emotionally charged performances of my life. The audience, a diverse tapestry of young and elderly attendees, which included soldiers in uniform and lyceum students from a military school, had all converged not out of mere curiosity but with a deliberate intent to listen to the authors they read and love.

Did we fail to notice all this earlier? Did we look deeply enough into the face of the Ukrainian south? I am confident that it, along with the entirety of Ukraine, is undergoing a transformation right before our eyes. Sellers in bookstores in Mykolaiv shared with us that "90% of Ukrainian book buyers are young people." New generations of Ukrainians are growing up, shedding the restrictive layers of obsessive Russification that existed prior.

But I want to conclude with something humorous. While in one Ukrainian city near the front, a soldier asked me if I was afraid of my then-upcoming work trip to Mexico, adding, "It's so dangerous there." Well... Let's shift our perspectives, engage with the world through our experiences, bridge gaps, and permit ourselves to see what's invisible. The world is undergoing constant changes, and as we evolve, we can gaze at each other during even the most difficult of times with curiosity and, occasionally, delight.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent.