Investigation: Sick Ukrainian children exploited in fraudulent charity campaigns linked to US, Israel

The Kyiv Independent traced a global network of deceptive cancer fundraisers that use sick Ukrainian children to raise millions, and uncovered a trail of companies stretching to the U.S. and Israel.

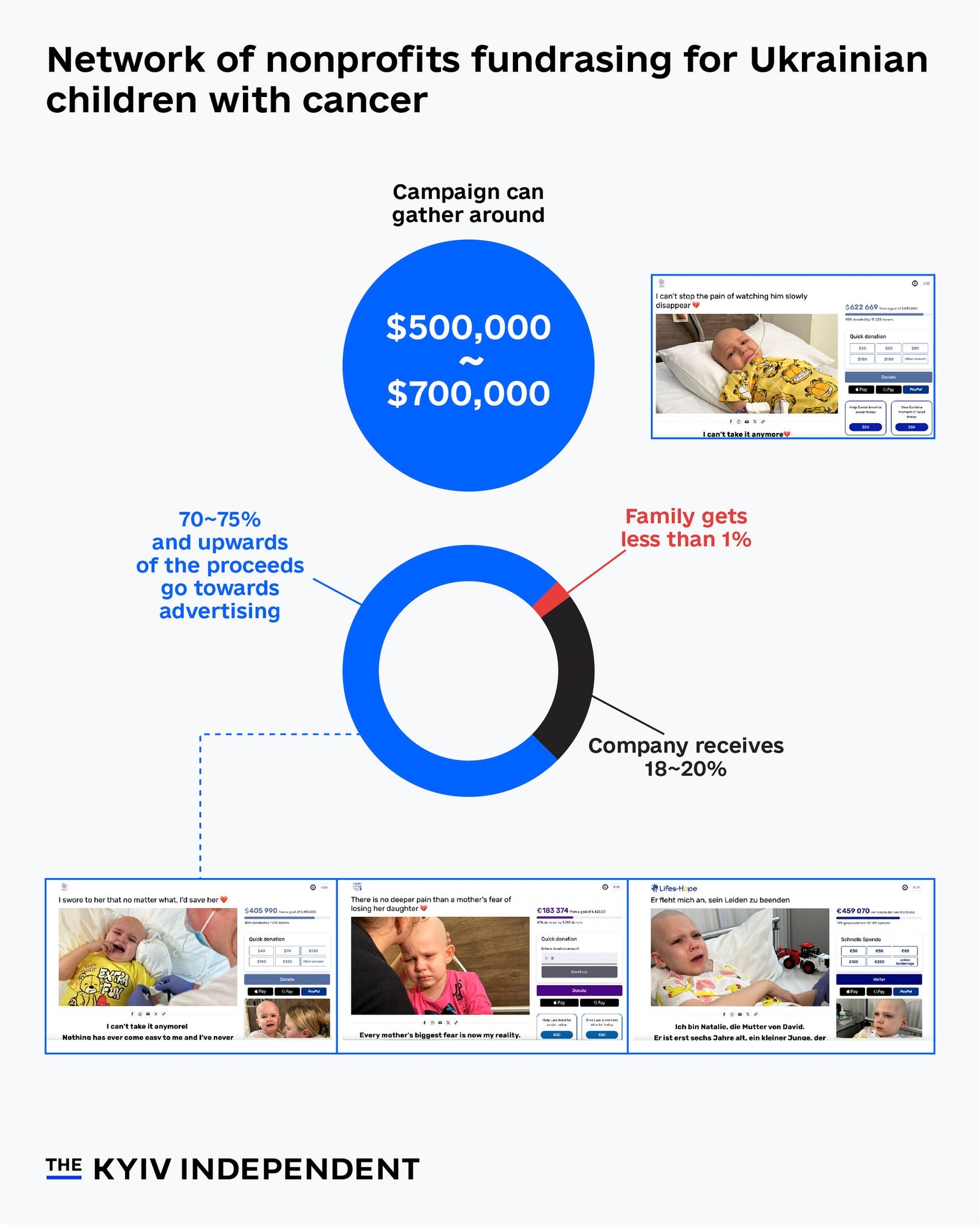

A network of nonprofits has raised millions in the name of sick Ukrainian children, but less than 1% of the funds appear to reach the children. (Karolina Gulshani / The Kyiv Independent)

Editor's note: This story is a collaboration between the Kyiv Independent and Factcheck Bulgaria.

Key findings:

- A network of nonprofits runs large-scale fundraising campaigns claiming to support Ukrainian children with cancer, yet less than 1% of funds raised appear to reach the children.

- These organizations are mostly based in the U.S. but maintain ties to Israel — reflected in Hebrew names and connections to a namesake organization in Israel.

- Fundraisers frequently use false information about children’s diagnoses, backgrounds, and names, raising suspicions about the legitimacy of the campaigns.

- Hope for Life, one of the key organizations behind the campaigns, admits that 70% to 80% of funds raised are spent on advertising, leaving only a small fraction for the actual cause.

- Hope for Life's statement suggests that advertising expenses for a single child would amount to $400,000 to $550,000, which does not align with time-tested, transparent fundraising practices, raising concerns about the potential misuse of funds.

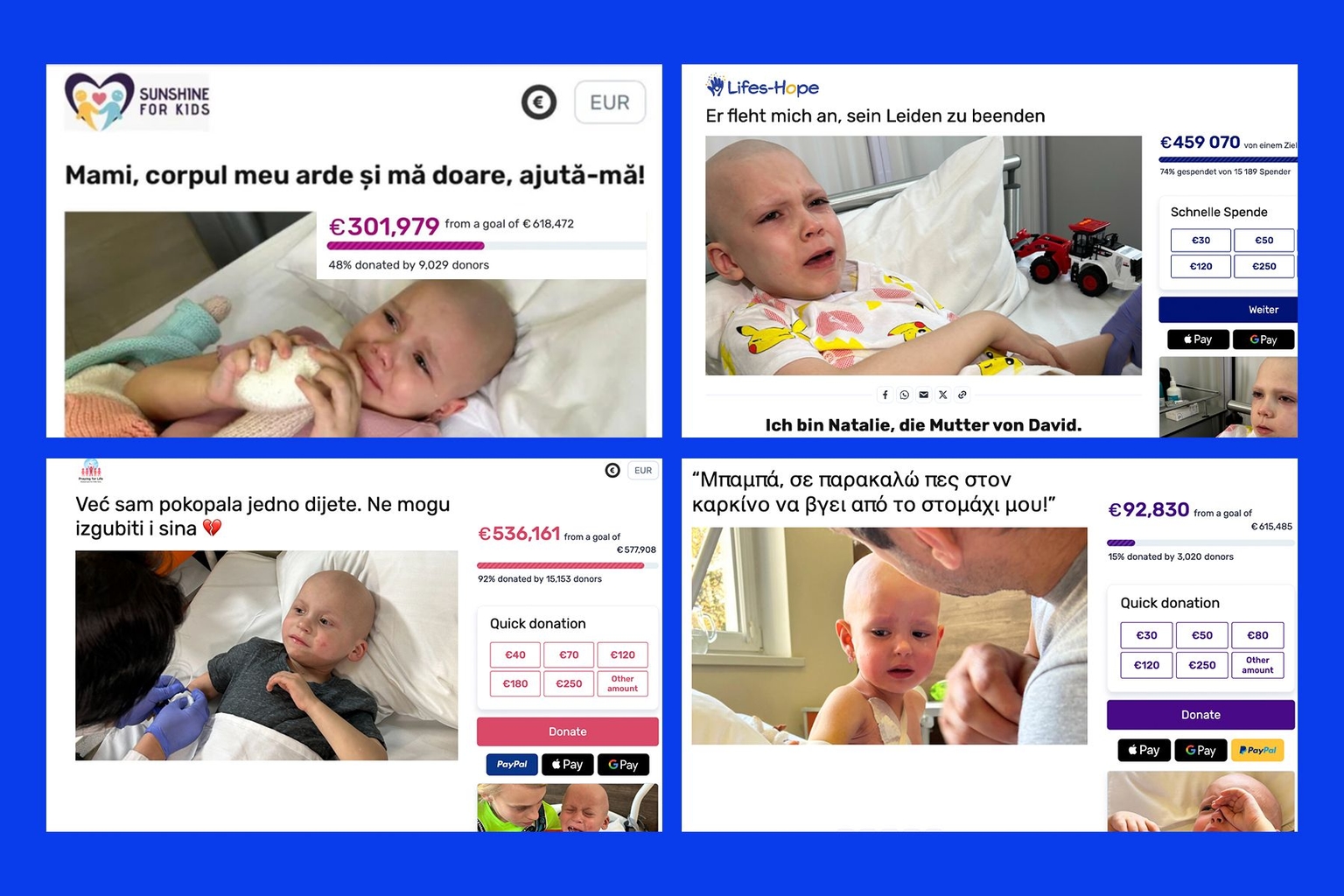

When scrolling through Facebook or Instagram, one may come across ads showing a crying child in a hospital bed, accompanied by a heartbreaking plea for donations to treat the child's cancer. The message is always urgent, stating that a child suffers from a severe form of cancer and needs treatment in the U.S.

Those ads appear worldwide and target local audiences in languages ranging from English and German to Bulgarian, Danish, Czech, French, Croatian, and many more. But behind the heart-wrenching images, our investigation finds that most of the money raised never reaches the children it’s supposed to help.

The Kyiv Independent identified several children and their parents featured in these campaigns and found that they live in Ukraine with no plans to receive treatment in the U.S. Each family has received less than $2,000 out of the $600,000 to $700,000 intended to be raised. Moreover, the investigation traced the network behind the entire fundraising operation.

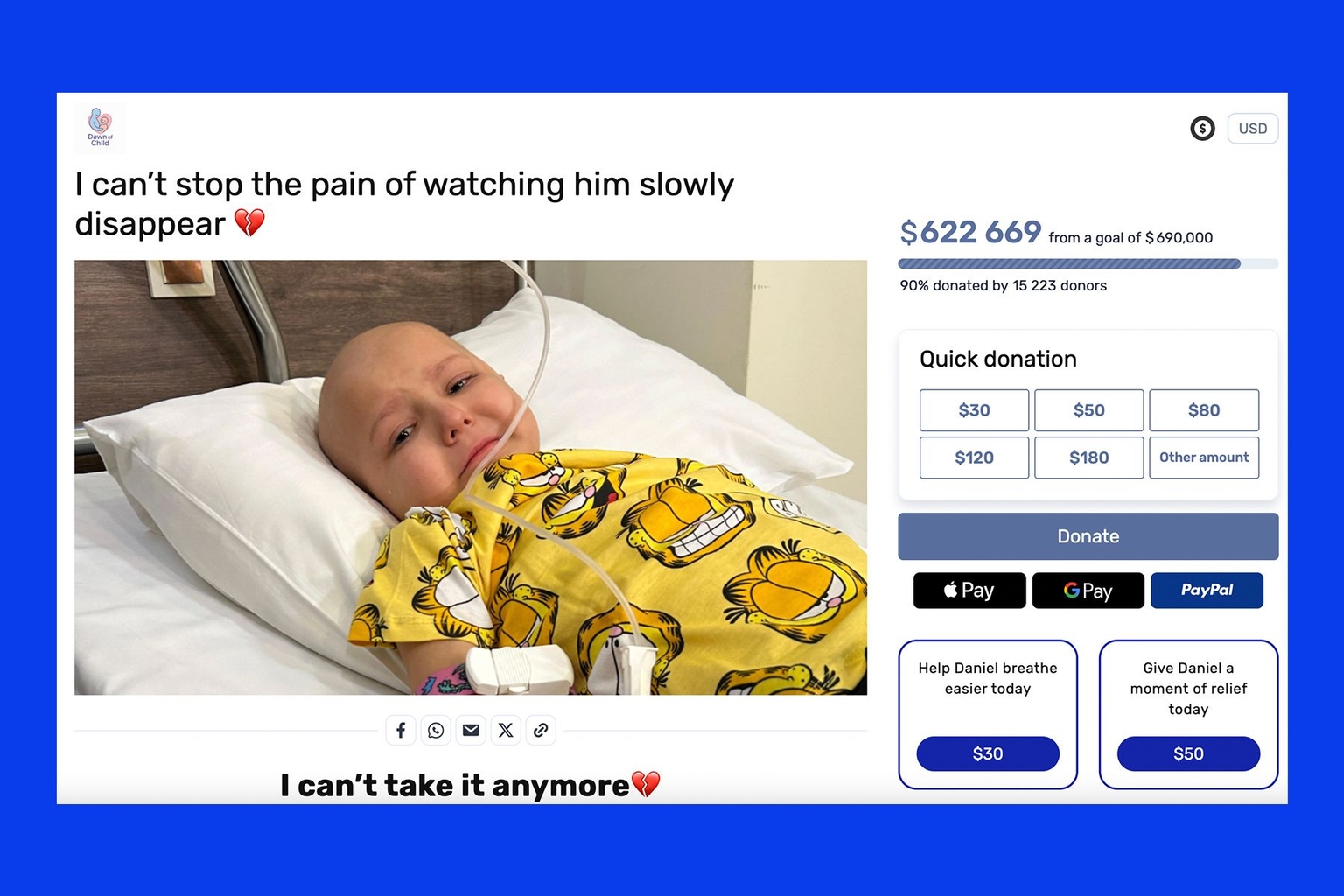

Campaign for a 7-year-old Daniel

Since July 2025, ads featuring a 7-year-old boy named Daniel have been circulating online. The ads, shown in countries such as the U.S., Germany, Bulgaria, and Lithuania, among others, appeal for help to cover his cancer treatment.

The campaign seeks to raise €585,796 ($690,000) via PayPal or direct credit card donations. As of Dec. 10, 2025, it has raised €532,376 ($622,669) from 15,223 donors.

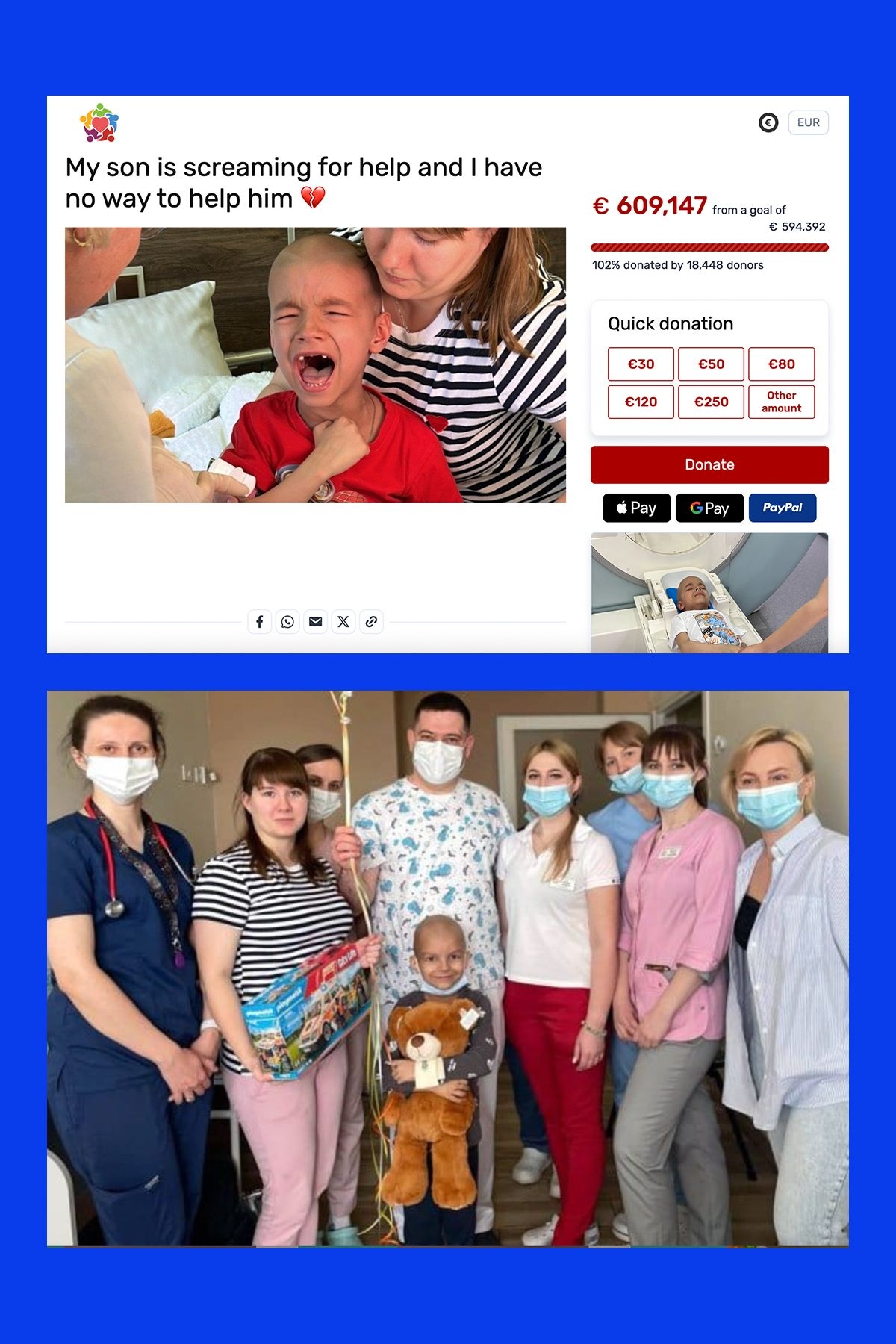

The first thing viewers see is a video of a crying child lying in a hospital bed, receiving treatment, while his mother comforts him.

The campaign page features a text, reportedly written by the child’s father, describing the harrowing story of his son’s battle with cancer and appealing for donations to fund his treatment in San Diego, California.

The message begins: “I can’t stop the pain of watching him slowly disappear. I can’t take it anymore. My son is only seven, he used to run around the house laughing. Now he can barely move his legs.”

The campaign claims Daniel has diffuse midline glioma, a rare and aggressive brain cancer. Each donation is publicly displayed alongside the donor’s name and the amount contributed, with many leaving supportive messages for Daniel and his family.

The authenticity of the donations cannot be fully verified, but several donors we contacted confirmed that they did make the contributions.

Nevertheless, the campaign has faced increasing skepticism, particularly on Reddit and Facebook, where users have raised doubts about its legitimacy.

A handful of media outlets worldwide have reported on these fundraisers, flagging them as potential fraud due to unclear information about the organizations’ activities and track record, missing medical documentation, and a lack of transparency about how donations are used. However, most of the publications were unable to identify the children featured in those fundraisers.

Using a combination of reverse image searches and facial recognition tools, the Kyiv Independent identified 11 Ukrainian children who had been featured in these international campaigns and spoke to four families. All four were surprised to learn that such large sums had been raised for their children, as almost none of it had reached them.

Real stories behind fishy fundraising calls

The boy featured in the campaign as Daniel turned out to be a Ukrainian child named Daneil, who lives in Ukraine. We spoke to the boy’s mother, Kateryna Kotelnykova, who was shocked to learn that her son was being used in such a fundraiser, as she said that most of the information provided about him was false.

Daneil’s actual diagnosis is leukemia, not diffuse midline glioma, and he receives treatment locally in Chernivtsi, a western Ukrainian city. The family is not seeking treatment in the U.S., as the campaign claims.

“We’re being treated in Chernivtsi, and we weren’t planning to go anywhere; thank God there is no such need yet, even though the child’s condition is serious,” Kotelnykova told us.

Through our research, we found additional campaigns featuring other Ukrainian children who appear to have been photographed at the same clinic in Chernivtsi. The stories seem to be crafted in the same manner, claiming that those children found a clinic for treatment in the United States and, on average, seek to raise $650,000.

Using facial recognition and reverse image searches, we identified three more Ukrainian parents whose children were used in these campaigns. This helped us gain a clearer understanding of the entire process, from the initial outreach to the launch of the fundraiser.

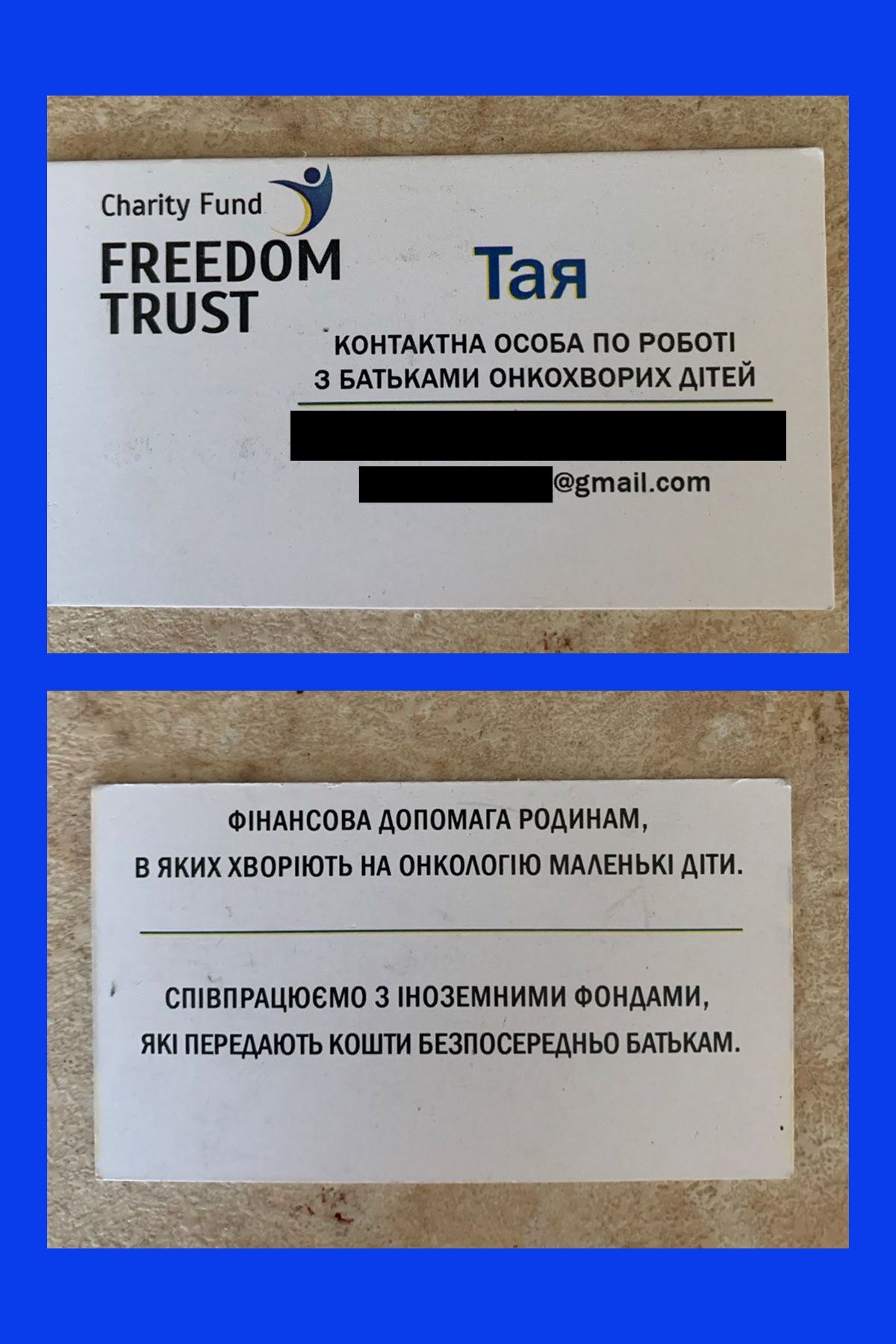

A couple of parents told us they had been approached in Ukrainian hospitals by a woman named Taya, who offered financial support for their child’s treatment, or were advised by doctors to contact her.

“Taya” asks parents to complete a form with their child's details, including medical information, and take a few photos, which she then sends to so-called foreign sponsors whose names she does not disclose to the parents. Selected children and their parents come to the clinic in Chernivtsi for professional photo and video shoots. Their parents then receive $1,200 to $1,700 in cash as one-time assistance from sponsors.

Parents sign a receipt confirming the funds have been received and give consent to the use of photos and videos for “reporting” to the sponsors. “Taya” also offers parents the option to sign an agreement authorizing the use of their child’s images and videos in fundraising campaigns.

Thinking it would bring more financial support, Kotelnykova signed without reading. “They offered their help; I agreed, since the child is sick and money is needed in any case,” she said.

Another mother, Natalya Polyanska, said she received Hr 50,000 ($1,181) after the photo and video shoot of her son Maksym in the hospital in 2024. She said she never received any more money — and was never promised any. However, the Kyiv Independent discovered an active fundraising campaign for Maksym — who was listed as Alex — that claimed to have raised over $700,000 for his treatment. When the Kyiv Independent questioned the organization about it in November 2025, the campaign was taken down.

Parents of three children told the Kyiv Independent they agreed to the fundraising campaigns but were unaware that they would use false information. In their cases, their children’s diagnoses, background stories, and even names were altered. Besides, none of them knew the campaigns would seek to raise so much money.

The fundraisers appear to anglicize the children's and parents’ names to make them sound more international, often changing the names completely. For example, the Ukrainian name Maksym was changed to Alex in a fundraising campaign; Serhii became Andrew, Ivan became David, and one mother’s name was changed from Anastasiia to Jessica.

‘Taya’: Broker connecting Ukrainian families with fundraisers

The Kyiv Independent identified “Taya” as Tetiana Khaliavka, a PR manager at the Ukrainian-Swedish medical center Angelholm in Chernivtsi.

The Kyiv Independent inspected the photos used in fundraising campaigns and confirmed that at least 11 Ukrainian children and their parents were photographed inside the Angelholm Medical Center. They didn’t undergo treatment there — the facility was only used for photos.

One mother reported that Taya coordinated the photo and video shoots inside the clinic, while two men who accompanied her handled the filming. She referred to them as “the father and the son.” A second mother stated there was only one man with Taya. Both testimonies suggest that the man in question is Taya’s son, Oleh Khaliavka, who also goes by the name Alex Kohen.

When the Kyiv Independent contacted him and asked about the photoshoots, he said he had been mistaken for someone else and hung up.

The Kyiv Independent obtained a business card that Khaliavka had given to a children's hospital worker at a medical conference so that they could refer parents to her.

The card lists only her altered first name, “Taya,” and describes her as a “contact person for working with parents of children with cancer,” adding that she “cooperates with foreign funds providing financial assistance directly to parents.” The card bears the logo of the Chernivtsi-based charity Freedom Trust.

Publicly, Freedom Trust focuses primarily on providing humanitarian aid to civilians living near front-line areas, as reflected on its Facebook page. When the Kyiv Independent journalist, posing as someone interested in supporting the fund, first contacted Freedom Trust’s head, Ihor Lohvinov, he said that they also have a program offering one-time financial aid from sponsors to children with cancer across Ukraine. Later, he would deny it.

When the Kyiv Independent journalist met with Lohvinov in Chernivtsi, now clearly identifying as a reporter, Lohvinov strongly denied any collaboration with foreign organizations.

At the same time, he said he knows “Taya” through volunteer work and allowed the use of his organization’s name and logo, which appears on her business card. Still, he said that Freedom Trust was not actually involved in the program of connecting Ukrainian cancer patients with foreign donors, and that no money passed through it.

The Angelholm Medical Center told the Kyiv Independent that “the clinic had never organized or conducted photo or video shoots of children with cancer and their parents,” and that it had no knowledge that the photos or videos of the children taken at the clinic were used for fundraising.

They denied any involvement in fundraising campaigns for the treatment of children with cancer: "Our clinic does not carry out, initiate, support, or participate in such activities in any form.”

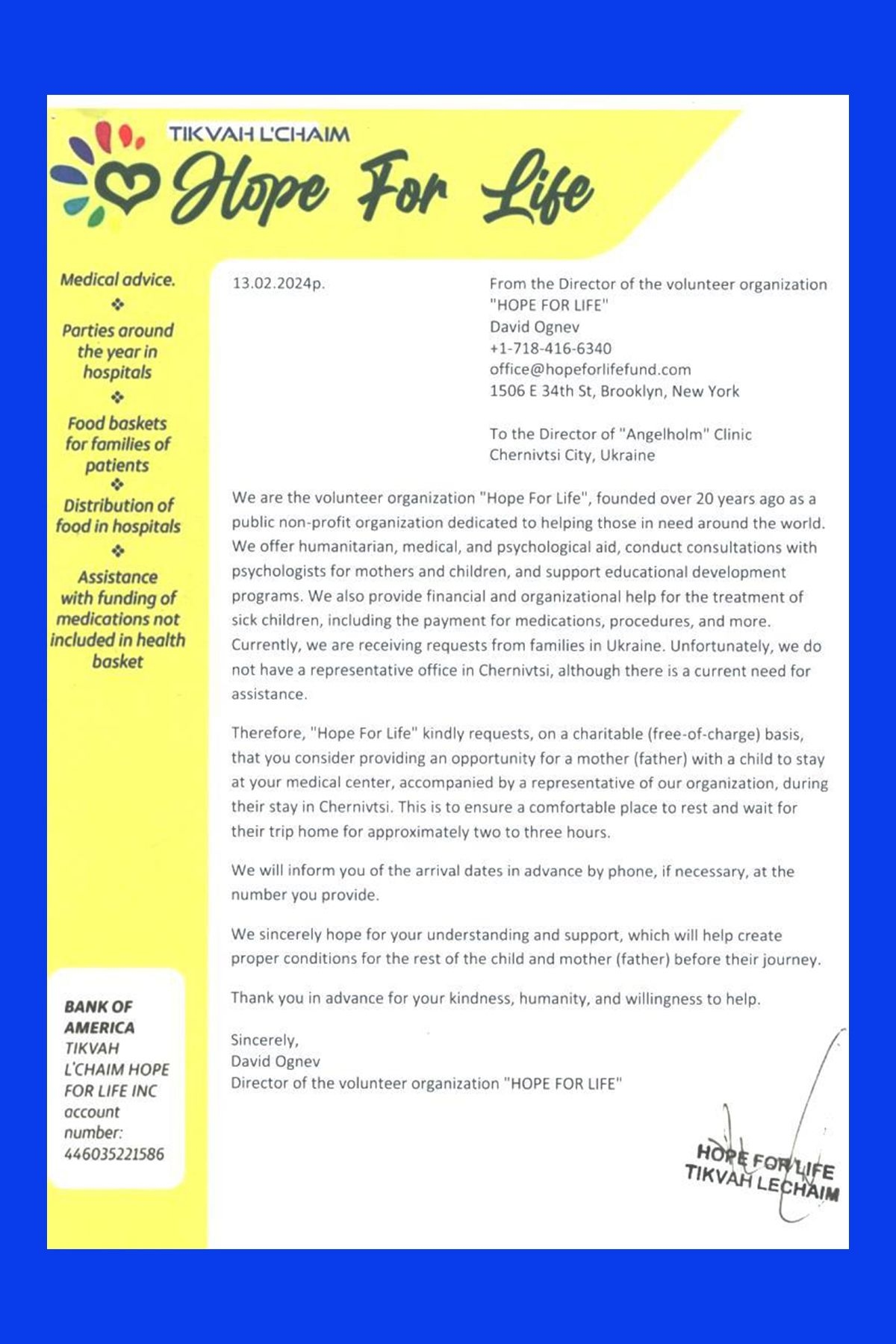

The clinic, however, said it was providing free short-term stays for children with cancer, who were allegedly passing through Chernivtsi, at the request of an American nonprofit.

The clinic provided the Kyiv Independent with a request it received from the American nonprofit organization Hope for Life (registered as Tikvah Lechaim Inc.) in February 2024. In it, the nonprofit was asking the clinic to provide a charitable, free-of-charge stay for a parent and a child, accompanied by a representative from Hope for Life, during their stay in Chernivtsi.

“This is to ensure a comfortable place for rest while they wait for their trip home, for approximately two to three hours,” the request states.

Angelholm Medical Center confirmed that Hope for Life directly contacted the clinic’s employee, Khaliavka, regarding these arrangements. The clinic granted its permission, allegedly not knowing that the “charitable stays” were actually photo-ops.

The clinic also said that after discovering their employee Tetiana Khaliavka’s (“Taya”) role in the campaigns, they decided to terminate her employment “in light of the facts uncovered and the use of official duties for personal purposes.”

“Taya” was coordinating staged photo and video shoots for children and their parents at the clinic, creating the impression they were receiving treatment. In reality, the children spent just a few hours over two days in the clinic, moving between rooms and changing clothes to appear as patients, one mother told us.

In a statement sent to the Kyiv Independent journalist, “Taya” said that she organized these shoots voluntarily and without pay, motivated solely by her desire to help children with cancer.

She explained that the initiative had come from the American organization Hope for Life, which approached her with the idea of collaborating to provide financial support to children in need.

Her role was allegedly limited to identifying families eligible for aid and organizing photo and video sessions upon the organization's request. Parents told the Kyiv Independent that she also handled the signing of agreements and the distribution of one-time financial assistance.

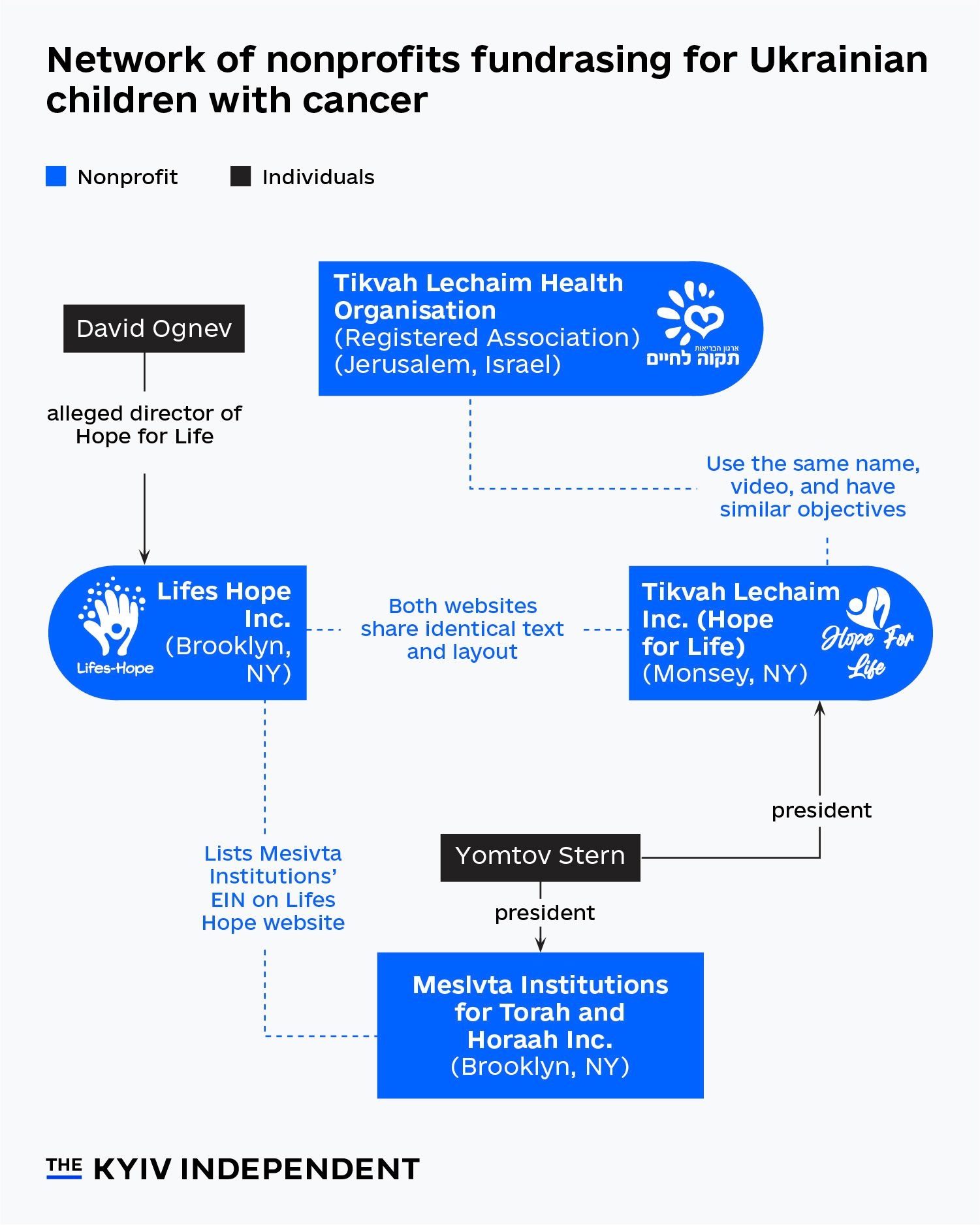

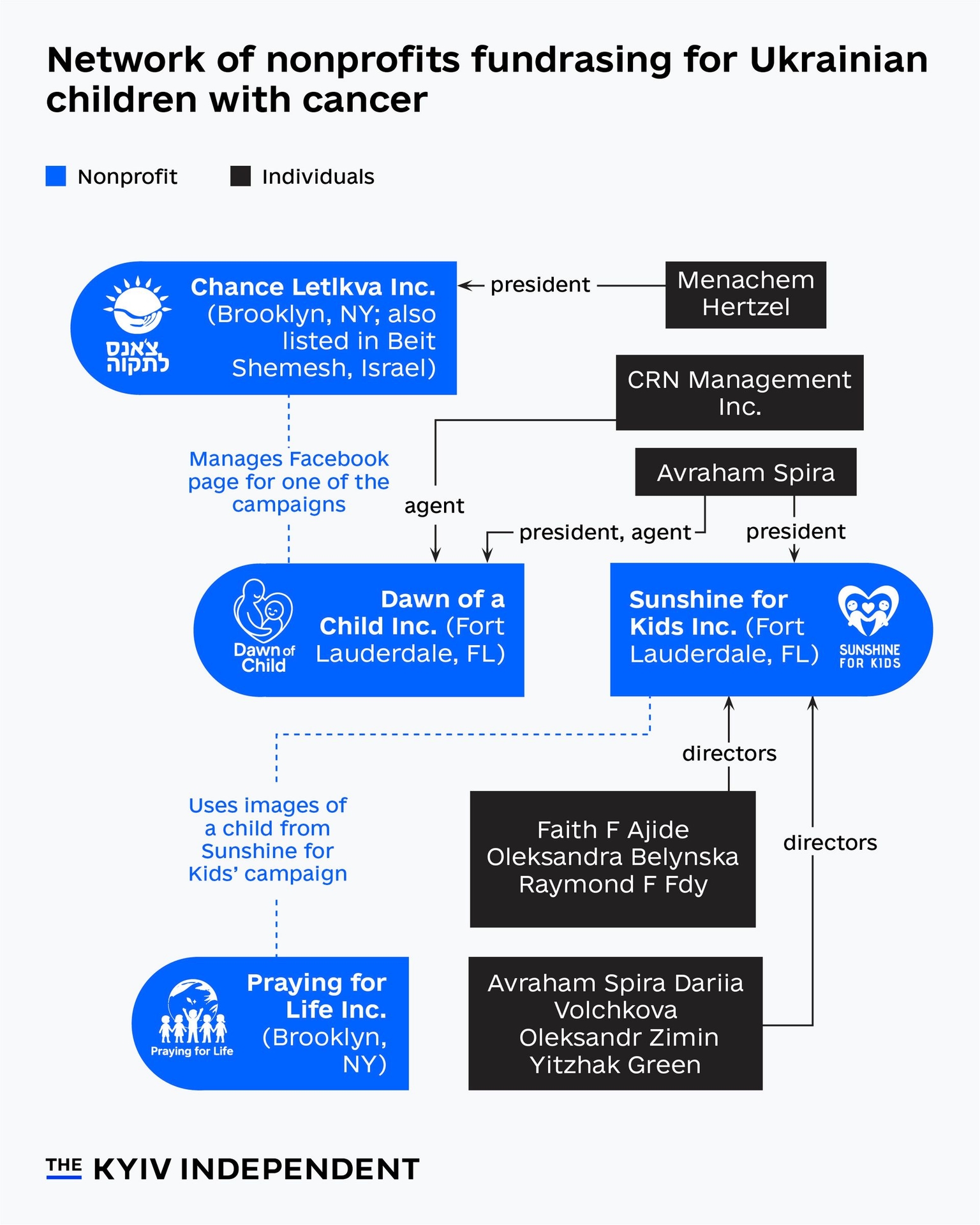

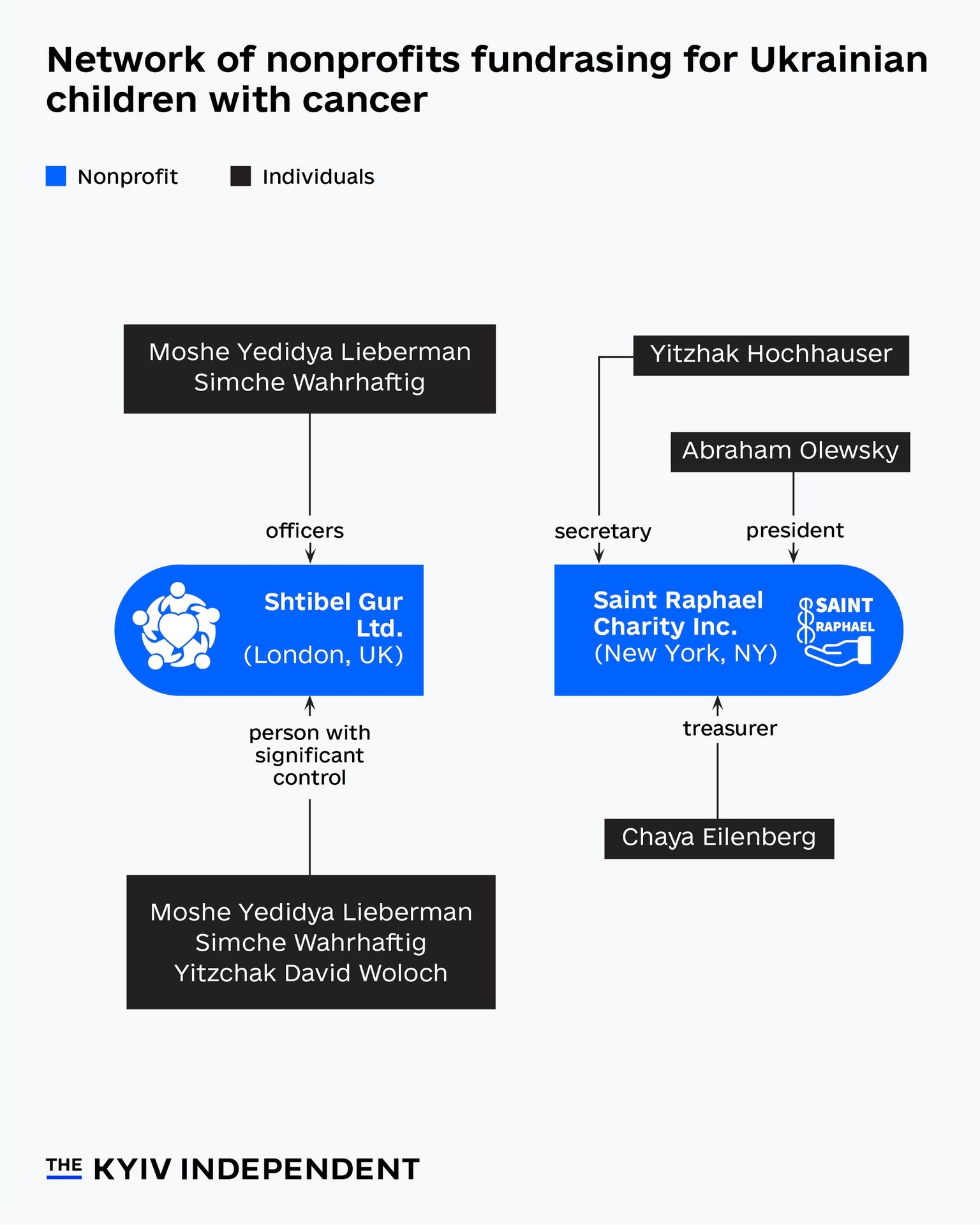

US network of nonprofits behind the fundraisers

The Kyiv Independent analyzed the websites hosting fundraising campaigns for at least 11 Ukrainian children with cancer. Contact details on these sites indicate they are operated by the following nonprofits:

- Tikvah Lechaim Inc. (the Hebrew name for Hope for Life)

- Dawn of a Child Inc.

- Sunshine for Kids Inc.

- Praying for Life Inc.

- Life’s Hope Inc.

- Shtibel Gur Ltd (Yiddish for “Gur prayer house”)

- Saint Raphael Charity Inc.

- Chance Letikva Inc. (“Letikva” translates from Hebrew as “hope”) appears as the company managing the Facebook page for a campaign supporting Daniel, one of the children.

The companies appear to be a network — some have the same president, others co-ran a fundraising campaign.

All are registered in the United States, except for UK-registered Shtibel Gur Ltd, which lists a U.S. contact address on its campaign page.

The network has ties in Israel. Campaigns are hosted on an Israeli platform. An Israel-registered Tikvah Lechaim appears to be related to the U.S. nonprofit of the same name, but didn’t manage the children’s fundraisers. An archived version of the website of the U.S.-registered nonprofit, Chance Letikva Inc., lists an address in Israel on its Hebrew-language page.

In a recent investigation into similar fundraising campaigns, the BBC traveled to the addresses listed for Chance Letikva in both the U.S. and Israel, but found no sign of the organization.

The U.S.-registered Tikvah Lechaim Inc. appears to be the central organization in the network: Their representatives were in touch, through “Taya,” with Ukrainian families whose children appeared in fundraising campaigns.

Public U.S. state registries list the directors and presidents of some of the organizations behind the fundraisers. However, the journalists were unable to find further information about them through open-source research.

Tikvah Lechaim Inc.’s 2024 Form 990 (U.S. nonprofit tax filing) lists only one person, Yomtov Stern, as president. However, a request submitted by Hope for Life to the Angelholm Medical Center in 2024 is signed by David Ognev, the organization’s director.

Using OSINT tools, the Kyiv Independent traced this name to a 21-year-old student at the City University of New York — in the same state where Hope for Life is registered. The journalists reached out to Ognev via social media and attempted to contact him by phone, but received no response.

The nonprofits didn’t answer the Kyiv Independent’s inquiries.

All campaigns are hosted via the Israeli platform Geev, which provides fundraising tools but reveals minimal information about the nonprofits running the campaigns. It typically lists only a landline — which doesn’t answer — and an email, allowing the nonprofits to maintain near-total anonymity.

Some of the nonprofits have standalone websites, which often feature AI-generated images and text.

Each campaign also maintains a Facebook page using targeted advertising to promote video content and maximize reach. In terms of transparency, the pages we analyzed generally disclose only one key detail: the countries of residence of the page managers, which are most often Israel and Portugal.

Interestingly, almost all of these Facebook campaign pages are blocked for users accessing them from a Ukrainian IP address — decreasing the chances of the children’s families seeing them.

Where does the money ultimately go?

The network’s online campaigns raise hundreds of thousands of dollars per child, but the families the Kyiv Independent spoke to have never seen this money. Where does the money end up?

Khaliavka, who goes under the name “Taya,” said she couldn’t say how the money was distributed, claiming her involvement ended when parents signed the agreement and received their initial small financial reward – typically $1,200 to $1,700, based on information from the parents.

From that moment, she said, the fundraisers were responsible for managing the campaigns and updating parents on their progress.

Parents we contacted confirmed that they do receive occasional calls afterward; these calls come from different international numbers, are conducted in Russian, and are often plagued by poor connections, leaving parents with little clarity on the campaigns.

When asked who was her contact, “Taya” provided a U.S. phone number for a man named Michael, who allegedly works in the customer service of the Hope for Life organization (Tikvah Lechaim Inc.). Meanwhile, OSINT tools indicate that the same number is also associated with Yomtov Stern, the alleged president of Tikvah Lechaim. “Taya” said they talk in Hebrew.

She also shared with us an example of the agreement that parents are required to sign in order to participate in the campaign. Section 4 states that families are entitled to a fee of $6,000 to $10,000, depending on the “success of the advertising campaign,” with a portion paid upfront and additional transfers “every 60 days… after deducting campaign-related expenses.”

Based on the average campaign total of €550,000 to €600,000 ($640,420 to $698,640), the promised payments amount to roughly 1 to 2% of all funds raised per child. Notably, the agreement does not disclose the total goal of the campaign.

Michael, a representative of Hope for Life, told the Kyiv Independent that 70–80% of the displayed total is allocated to advertising to promote the campaign. After platform commissions, the nonprofit receives about 18–20% of the raised money. Of that amount, it retains a portion for operational expenses. He did not specify how much ultimately reaches the parents.

"If it's $300,000, maybe we get $70,000–80,000, or $60,000, and out of that, we have expenses — for wire and all that… to make the videos and to make the pictures, and whatever is left, we spend on the family,” Michael said.

Viacheslav Bykov, CEO of Tabletochki, Ukraine’s leading charitable foundation for children with cancer, which discloses its funders and publishes financial reports, called such ratios “outside global standards” and “completely unjustifiable.”

“Globally, I would place the acceptable (fundraising expense) ratio at roughly 10% to 25%,” he said. Tabletochki’s standard requires about 82% of funds to go directly to assistance.

Michael from Hope for Life denied wrongdoing in a phone interview, saying they “do everything by the book” and do not alter children’s diagnoses. But campaign records contradict that claim: In at least four cases this investigation verified, diagnoses were changed, including two children with leukemia who were presented as having diffuse midline glioma.

At the same time, Michael acknowledged that families’ names were routinely modified, saying parents “asked in the contract not to use the names.”

The mothers the Kyiv Independent spoke with gave a different account: None were told that their children’s names or diagnoses would be altered. The agreement provided by “Taya” contains no mention of such practices either.

Michael said the campaigns are spread across multiple websites due to payment-processing limitations: “There are other companies that help us in order to receive the funding, because you cannot receive it all in one location.”

Still, as of early December, the campaign for the seven-year-old Daniel — Daneil Kotelnykov — remained active online, continuing to raise donations.

Kateryna Kotelnykova, Daneil’s mother, said she was promised some money in November but has yet to receive anything. When the Kyiv Independent showed her the campaign page, she was surprised by the goal of the campaign — more than $690,000. As of early December, 90% of the funds had been raised.

“When I looked at the amount, I started wondering what exactly they planned to give me,” Kotelnykova said.

Natalya Kiryanova, whose son Ivan also appears in one of the campaigns, was outraged when she learned how much had been raised using false information. She said that Ivan fell ill after their home near the front line in Orikhiv, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, was bombed by Russian forces.

"It's just so painfully offensive that they’re raising such large amounts, profiting off these poor children who’ve suffered psychological trauma from the war, and now, on top of that, are struggling with cancer,” Kiryanova said.

Note from the author:

Hey! This is Linda, the author of this story. Writing and untangling it was emotionally challenging, because it deals with the deeply personal and difficult topic of helping children with cancer. My hope is that by shining a light on how fundraising campaigns actually work, and where the money goes, readers will feel empowered to ask questions, dig deeper, and make informed decisions before donating or getting involved.

If you want to help us produce more investigative stories like this, consider becoming a member of the Kyiv Independent.