Dmytro Yefremov: China’s stance on Russia’s war reveals wider strategic aims

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent.

Amid Chinese President Xi Jinping’s official visit to Moscow on March 20-21, observers were fixated on whether the meeting would indicate an agreement on the supply of weapons to Russia by China.

While no official agreements on the provision of arms have been announced, there remains reason to believe that such cooperation may be possible.

Earlier, CIA Director William J. Burns and U.S. State Secretary Antony Blinken took center stage, stating that they had data indicating that China’s leadership is actively considering such provisions. U.S. President Joe Biden has warned China against taking such steps.

In response to the accusations, then-Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang said Beijing has not provided weapons to either side. Regarding Russia’s war, he added that China “always makes its own judgment and decides on this position independently based on the merit of the issue.”

The course of China’s foreign policy is increasingly shifting toward an escalating confrontation with the United States.

At the opening of the National People’s Congress session on March 6, Xi Jinping said, “Western countries – led by the U.S. – have implemented all-round containment, encirclement, and suppression against us, bringing unprecedentedly severe challenges to our country’s development.”

It is obvious that China is looking for means of counteracting its rivals, one of the forms of which could be arms support for Russia in its war against Ukraine. Beijing continues to view Russia’s attack on Ukraine as a reaction to NATO’s so-called provocative eastward expansion, which goes against Russia’s security interests.

For many years, China has undertaken great efforts to position itself as an alternative to the West as a world leader, forming its own pole of influence in opposition to it.

Now, this political line is on the verge of a radical test. Ukraine’s victory over Putin’s forces will mean a reaffirmation of the United States’ global leadership and the values it promotes: a rules-based world order, democracy, and individual freedoms. The influence of China, which views the world order through the prism of its own leadership, will then decline.

It is for this reason that, at the start of 2022, China adopted a specific, detached position on the brewing crisis in Europe. By not supporting Ukraine, China tried to avoid embodying the American position so as to prevent the indirect legitimization of its leadership.

The need to maintain a detached position is dictated by Chinese tradition, tactics, and strategy. The official line of China’s foreign policy since the mid-twentieth century has been a doctrine of “peaceful coexistence.”

It suggests respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of other states, the rejection of aggressive foreign policy and interference in the internal affairs of other countries, and the search for common ground for mutually beneficial cooperation. International Chinese initiatives and speeches have traditionally been filled with elements that refer to these principles.

However, there have been cases in the history of China’s foreign policy that have gone against this doctrine: the Sino-Indian clashes of the 1960s, the Sino-Vietnamese War of 1979, and interference in Cambodia, to name a few. American sources point to China’s involvement in supplying small arms to the Mujahideen during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

These precedents indicate the possibility that China is departing from its traditionally declared principles to achieve important current interests.

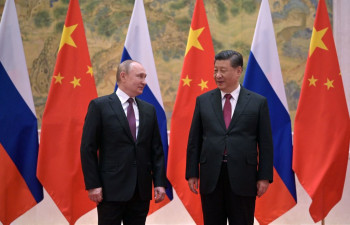

Chinese President Xi Jinping (L) arrives at the Kremlin for talks with Russian President Vladimir Putin on March 21, 2023, in Moscow, Russia. (Photo by Contributor/Getty Images)

In 2022, China’s tactical actions were aimed at artificially reducing the significance and severity of the events taking place in Ukraine. When describing Russia’s full-scale war, Beijing made a point of not mentioning the names of the involved parties, much less specifying Russia’s guilt for its actions in Ukraine.

In spite of the number of civilian casualties, Beijing stubbornly referred to Russia’s war as a “crisis” as opposed to a “war,” likely cognizant of the fact that the term “war” imposes strict obligations on permanent members of the UN Security Council. On a separate note, it should be mentioned that China has no experience in the meaningful mediation of international conflicts.

To avoid having to acknowledge Russia’s guilt when investigating the war, Chinese officials have tended to shift focus from addressing the cause of the war to its consequences, especially the humanitarian fallout.

This tactic of de-actualization allows Beijing to maintain its line of “peaceful coexistence,” as well as legitimize its seemingly passive position on the war. Under these conditions, China retains its ability to respond only to international crises that are convenient for it to demonstrate a form of leadership.

read also

China’s position on Russia’s war against Ukraine is also in part strategically aimed at trying to convince its neighbors, especially in Southeast Asia, of its alleged commitment to peace. The thought that Beijing might follow Putin’s model will provoke security concerns in the Indo-Pacific – states in the region will search for defense strategies more forceful than their current approach of “active neutrality.”

If China is even indirectly involved in the war by expressing open support for Russia or supporting it with arms supplies, the response to the growing threat will necessarily be new anti-China security alliances. In order to avoid such scenarios, Beijing will have to remain neutral, reject a military solution to the war, and demonstrate a commitment to achieving peace.

Western policymakers are now trying to apply pressure on China’s desire to build an image of itself as a “peace-loving” hegemon. Pushing back against China’s ambiguous intentions amid Russia’s war forces Chinese officials to leave their comfort zone and elaborate on their positions.

This result is beneficial for the West, as it narrows China’s ability to maneuver and forces it to play by its rules. It is also beneficial for Ukraine, as it provides some insurance against unfriendly actions and makes it easier to win the war.