A Russian opposition figure tries — and fails — to mythologize Zelensky

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, President Volodymyr Zelensky has come to occupy a singular place in the global imagination: not merely as Ukraine’s president, but as the voice through which the country’s courage and endurance are made legible to the world.

While an ongoing political scandal in Ukraine has involved some in Zelensky’s own inner circle, for many at home and abroad, it is in his public presence that the war’s meaning, its stakes, and its moral contours are most clearly felt beyond Ukraine’s borders.

It is hardly surprising, then, that so many are drawn to write about him. What is more striking is that this fascination extends even to members of the exiled Russian intelligentsia, whose typical attitudes toward Ukraine — sometimes ambivalent, other times hostile — underscore the power of Zelensky’s presence.

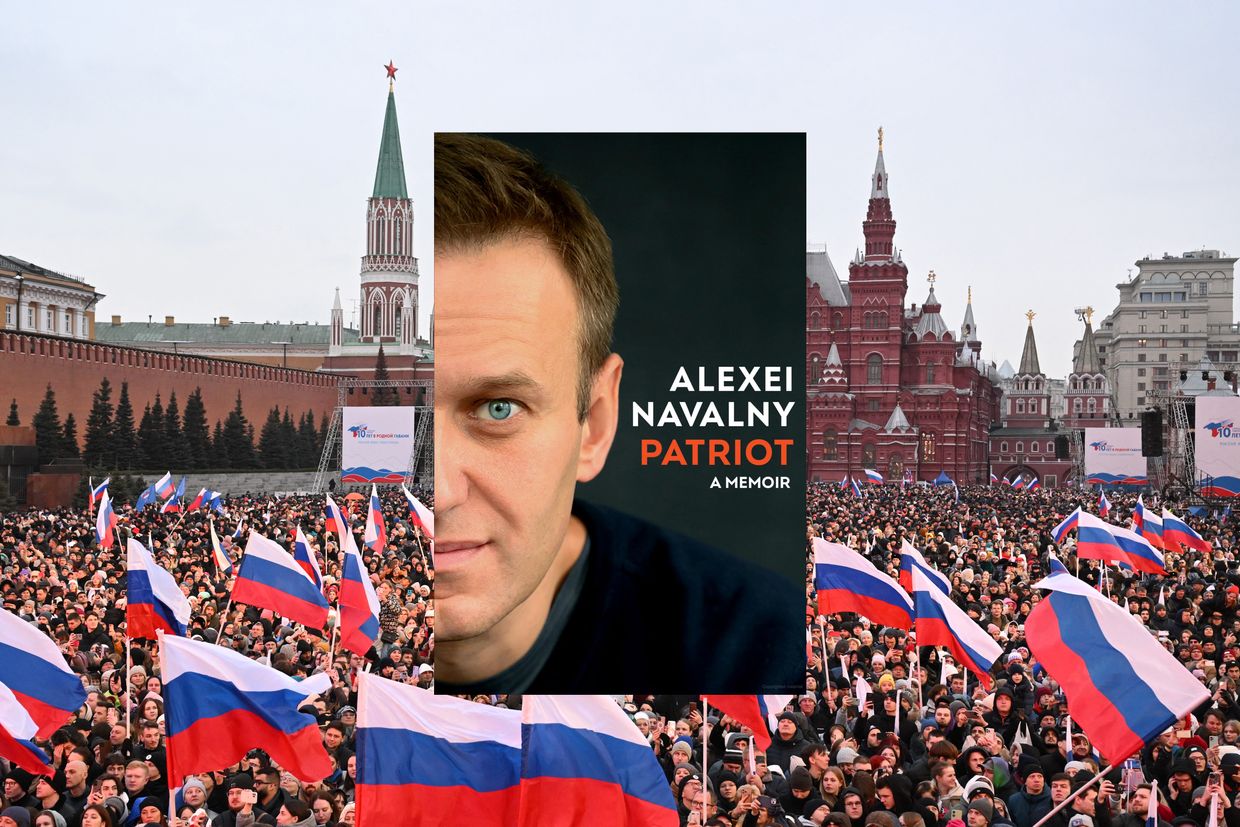

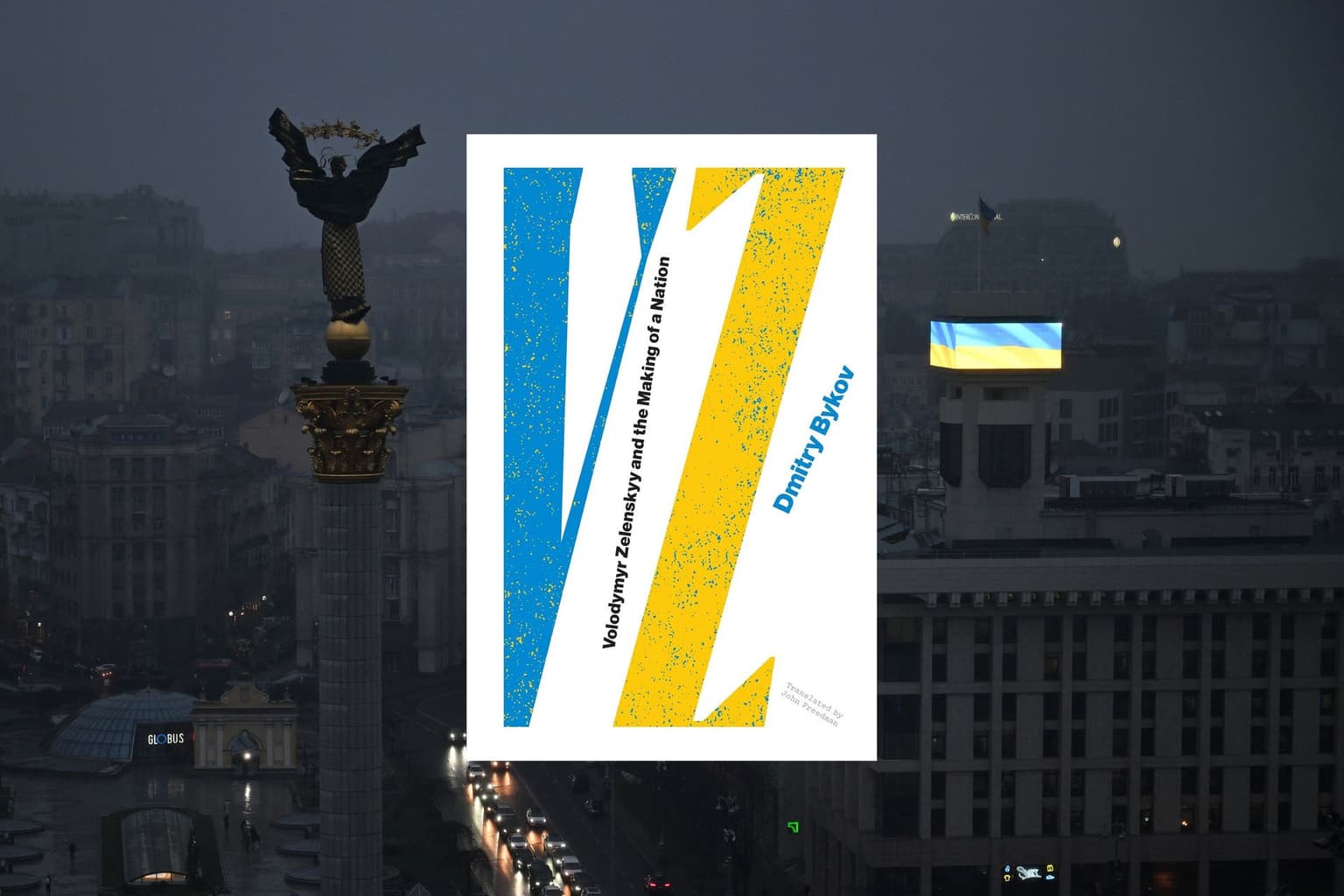

“VZ: Volodymyr Zelensky and the Making of a Nation” by Dmitry Bykov traces the arc of how Ukraine’s president went from the industrial streets of the eastern city of Kryvyi Rih to the bright, self-conscious world of television satire, and finally to the unforgiving stage of history, where an actor became a president, and a president became a symbol of defiance amid Russia’s full-scale war of total annihilation.

Bykov has long stood in the crosshairs of the Kremlin. He left Russia permanently in 2022, and since then, the state has pursued a series of criminal cases against him in absentia. He was also branded a “foreign agent,” a designation that functions less as a legal category than as a means of policing and constraining voices deemed politically inconvenient.

While Bykov has a clear anti-war stance and has long criticized the Kremlin, there are still a number of problems with the book — beginning with the title itself.

On the surface, the initials simply denote the first and last name of the Ukrainian president, but in the context of the Russian invasion, they also evoke the letters painted on Russian military vehicles, signs that have become shorthand for the machinery and ideology of aggression. In Russia, the letter “Z” in particular has been transformed into a rallying symbol for the war, appearing on flags, clothing, and social media as a sign of support for the invasion.

The most conspicuous weakness of the book is its sheer length. For all its setbacks, Simon Shuster’s “The Showman” offers a far more disciplined and coherent account of Zelensky’s political life and the path that led up to it. The result of an apparent lack of editorial restraint in Bykov’s case is a book swollen with anecdotes and digressions, five hundred pages that might more profitably have been two hundred.

The tangents are among the book’s more exasperating features, sprawling into miniature biographies of current and former figures of Zelensky’s inner circle. For example, we are treated, at unnecessary length, to the life and reflections of Oleksii Arestovych, a former presidential adviser for whom Bykov’s admiration borders on the devotional.

Bykov seems to lionize Zelensky not simply as a political figure but as a hero of the creative class with the hope of reassuring both himself and the rest of the Russian intelligentsia that their authority in this world has not entirely evaporated — that they, too, can achieve something great someday, even if they failed to do so in their home country.

These digressions serve mostly to dissipate whatever narrative momentum the book manages to build, leaving the reader with the sense of an author unable, or unwilling, to distinguish the essential facts from the merely adjacent ones. Bykov attempts to justify these biographical tangents by claiming that the very concept of the book is "about how God forces man to perform in a divine drama, and fulfill tasks put forth by God," and that men like Arestovych fit this description as much as Zelensky does.

For all his admiration of Ukraine’s resilience, however, Bykov still occasionally inhales the lingering fumes of post-Soviet discourse on Ukrainian-Russian relations, which may explain his fascination with a toxic figure like Arestovych. In a transcript from their interview included in the book, Bykov tells Arestovych that he does not see Russia’s full-scale war of aggression against Ukraine as "a colonial war," meaning he doesn't see one of Russia's goals as the destruction of Ukrainian culture. Arestovych agrees, declaring that "anti-colonial discourse is one of the leading idiocies being foisted upon us."

This imperialistic dog whistle sounds throughout the book, most notably in Bykov’s repeated references to Ukrainian culture as “folkloric,” and in his designation of Ukraine as an “emerging nation” rather than one that reclaimed its hard-won independence with the collapse of the Soviet Union. His historical and cultural references are firmly embedded in the Russian cultural framework, with minimal — if any — engagement with Ukrainian contexts.

Bykov argues that the construction of a nationalistic state is “not so much an unattractive idea as it is an unworkable one” and laments that the Russian language did not receive the recognition accorded to Ukrainian in the post-2014 climate, having boasted from the opening pages of the book that he is seen as an “enemy” of Ukrainian nationalists as he is of the Kremlin.

At the same time, Bykov is a shrewd and self-aware writer, evidently conscious that his worldview may be flawed or at the very least subject to the winds of change. It must be acknowledged, then, that he calls the Russian language after 2014 “the language of lies and hatred” and that Russians will be tasked with “cleansing it for a long time.” He also acknowledges that, under the extraordinary circumstances of Russia’s war, the Ukrainian government is justified in enacting laws that limit the use of the Russian language in public life, and that Ukraine is a nation of people that simply cannot be conquered.

An intellectual of the Russian opposition in exile who is eager to praise Ukrainian leadership amid the full-scale war is not an inherently bad thing. On the surface, it signals a departure from the centuries-old tendency of Russians who view Ukrainians as “little Russians” perpetually destined to follow the cultural and political lead of those in St. Petersburg or Moscow. Rightfully so, Bykov sees that the future of not only Ukraine but Russia is being decided from Kyiv.

However, the art of mythmaking seldom flourishes in the present tense — it relies on the passage of time, which enables an author to evaluate their subject’s flaws as thoroughly as their virtues. Bykov’s eagerness to explain away all of Zelensky’s perceived flaws feels especially rushed when the president is currently facing the biggest scandal of his political career.

For Bykov, it is Zelensky’s instinct as a performer — the quest for recognition that began on the stage — that most powerfully defines him as a formidable leader. In this light, Bykov seems to lionize Zelensky not simply as a political figure but as a hero of the creative class with the hope of reassuring both himself and the rest of the Russian intelligentsia that their authority in this world has not entirely evaporated — that they, too, can achieve something great someday, even if they failed to do so in their home country.

This becomes more evident as Bykov repeatedly attempts to entwine himself with Zelensky, declaring they both “belong to the glorious tribe of creative laborers” and suggesting that Zelensky “rehabilitated not just the creative Intelligentsia — he defended the meaning of our entire life” through his leadership during the full-scale war.

But the clumsiness of such hagiography may just reveal something essential about one of the main differences between Ukrainians and Russians. Bykov’s perplexed musings on Ukrainians’ disposition to reject authority inadvertently highlight the very reason Ukraine has avoided the authoritarian nightmare that haunts Russia: namely, that Ukrainians are quick to remind their leaders they are expected to serve the public good, and that doing so requires those in power to be held accountable each day — not treated as objects of unquestioned reverence, no matter how influential and powerful they may be.

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, thanks for reading this article. There is an ever-increasing amount of books about or related to Ukraine, Russia, and Russia's ongoing war of aggression against Ukraine available to English-language readers, and I hope my recommendations prove useful when it comes to your next trip to the bookstore. If you like reading about this sort of thing, please consider supporting The Kyiv Independent.