Where does Russia expect Ukraine’s counterattack? Overview of defensive lines

As Ukraine gathers forces for the counteroffensive, Russia continues to build defensive lines on a massive scale.

The lines are especially formidable in the southwestern part of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, where many observers expect the main Ukrainian assault to strike.

But defenses have been prepared along pretty much the entire front; in occupied Crimea and inside Russia. They incorporate trenches, bunkers and strongpoints, infantry and vehicle shelters, anti-tank ditches, pyramidal concrete tank barriers called dragon's teeth, and minefields, as well as terrain and water features.

When properly manned, these lines could pose a tough challenge without an easy solution.

Russia’s ability to properly man them is debated. The Russian military can’t hope to defend the entire 800-kilometer front line with equal vigor. During the defense, large Russian formations may have to fall back to prepared positions in a coordinated fashion — Russia’s shown that its large-scale maneuvering capability isn’t the best.

However, fortifications may allow Russians to put up heavy resistance in key areas, possibly slowing down the Ukrainian forces long enough for reinforcements to arrive.

Here is an overview of what Russia’s defenses and troop concentrations look like at different parts of the front and what that can tell us about the battles to come.

Kharkiv and Luhansk oblasts

Russia’s easternmost defenses start at the Kharkiv Oblast’s national border and run down through Pokrovske and Svatove, to around Kreminna and Bilohorivka in Luhansk Oblast, a distance of around 140 kilometers.

Satellite images show that this stretch consists primarily of a single, solid belt of defenses set back from the current front line by distances of 5-20 kilometers. However, Russian forces have begun to construct another layer in northern Luhansk Oblast and Kharkiv Oblast, freelance OSINT analyst Pasi Paroinen observed.

Karolina Hird, a scholar with the Institute for the Study of War, said that in case of a Ukrainian attack here, the Russian forces seem like they intend to fall back just once to that one defensive line and try to hold it.

“That’s kind of their only option – to hold that line,” she said. “And then if there’s a Ukrainian breakthrough on that line, that will allow Ukrainian forces to push into occupied Luhansk Oblast.”

According to multiple reports, the Kupiansk axis in Kharkiv Oblast is guarded by a fairly dispersed force grouping, including the battered 1st Guards Tank Army’s 47th Tank Division and the 6th Combined Arms Army’s 138th Separate Guards Motorized Rifle Brigade.

The Kreminna axis in Luhansk Oblast further south has a much higher force concentration, with elements from the Western Military District, Central Military District, Airborne troops, Spetsnaz (Russian special forces), militias from occupied Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, and other irregular formations.

Multiple groupings, including the elite airborne forces have been fighting in the area for months, taking losses without capturing territory. These troops are unlikely to be fresh.

Donetsk Oblast

The defensive lines continue from the west of Sievierodonetsk, running down along the regional border between Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts until reaching the area behind Bakhmut where they peter out.

These defenses were similar to the single-layer hard line to the north, according to the ISW’s April data. New fortifications started in the winter have been completed in the area recently, including in front of Lysychansk and Popasna, Luhansk Oblast.

According to the ISW, another line of defenses runs vertically from the south of Bakhmut, down to the national border.

However, the rear just east of Bakhmut is surprisingly unfortified, reflecting the fact that this is where Russia gained the most recent ground with Wagner Group’s offensive. “It’s too hot of a front line to build anything extensive,” said Paroinen.

Hird pointed out that there are reservoirs and rivers behind Bakhmut that act as natural barriers impeding mechanized movement. As for the existing defenses, the question is who will man them, as there are few conventional Russian forces around Bakhmut other than some Russian Airborne (VDV) units.

The area around occupied Donetsk itself is well-fortified after close to 10 years of both sides building up their defenses. There are extensive fortifications around the Avdiivka area and running from the edge of Donetsk to Marinka. Because these defenses have been there for a long time, they’re often omitted from recent maps of Russian defensive lines.

As a result, Donetsk and its surrounding settlements are a fortress, which would be very difficult and unsuitable for offensive operations. The forces here include many elements of the 1st Donetsk Army Corps, Russia's Southern Military District, the Northern Fleet, and multiple irregular and volunteer battalions.

Western Donetsk Oblast and eastern Zaporizhzhia Oblast

The Russian lines starting near Vuhledar, Donetsk Oblast, become much more sparse and scattered. This state of affairs extends all the way to north of Kamianka in Zaporizhzhia Oblast.

There is no hard line for Russian forces to fall back to and more of a reliance on the water and terrain features of the river-crossed farmland. What trenches and isolated strongpoints exist are probably unmanned for the most part.

The force groupings closer to Vuhledar were “utterly clobbered,” said Hird. “Elements in the area are in absolute shambles. They’ve been trying to take Vuhledar since October and have taken so many losses, entire naval infantry formations were restaffed in 3-4 iterations.”

The Russians along the spottily-defended area are exhausted and there are known issues with command and poor command structure and culture, experts said.

These units include Eastern Military District elements, the Pacific Fleet marines, VDV, some special forces, as well as a few private military companies and irregulars.

Zaporizhzhia and Kherson oblasts

The hardest going will be in the south, where Russian forces prepared for a defense in depth. There are multiple layers of defensive lines, running up to dozens of kilometers deep. Defensive positions radiate down critical roads and encircle important settlements like Tokmak, Melitopol, and Kamianka.

The roadside fortifications can be seen all the way down towards Crimea. A double line guards the narrow crossing from the mainland into the peninsula and Crimea’s main roads are also being lined with defenses.

Trenches have even been dug along Crimean beaches, which are unlikely to do much, since Ukraine doesn’t have enough of a navy to conduct big landings but they reveal the Russian forces’ concern about the counteroffensive.

But the defensive lines in the southern Zaporizhzhia Oblast are formidable. There are multiple layers of antitank ditches and dragon’s teeth, as well as sheltered infantry and vehicle fighting positions.

Russians have recently been spotted adding more positions between the defensive line and the forward line of contact.

If heavily pressured, Russian forces here will be able to continually fall back to positions behind them, while laying down damage and slowing down the Ukrainians, with the aim of bogging them down and picking them apart.

They will have to do so, in fact, because it’s unlikely that all of these defenses are manned right now. The forces in this part of the front contain the battered remnants of those that withdrew from Kherson and units redeployed from other axes of attack.

However, they’ve also seen months of relatively low-intensity fighting, meaning they’re fresher than their comrades in Donbas.

Likely groupings include elements of the Southern and Eastern Military Districts’ combined arms armies, the Black Sea Fleet marines, Spetsnaz, as well as multiple volunteer battalions.

In Kherson Oblast, the defensive positions start right on the left (eastern) bank of the Dnipro River, which has been heavily mined. Dragon’s teeth and pillboxes further harden the bank. Analysts think it’s unlikely that Ukrainian forces will conduct a large strike across the river.

Russia's defensive line north of Tokmak, Zaporizhzhia Oblast

Russia’s layered defenses, especially in the south, pose a daunting challenge to Ukraine’s forces.

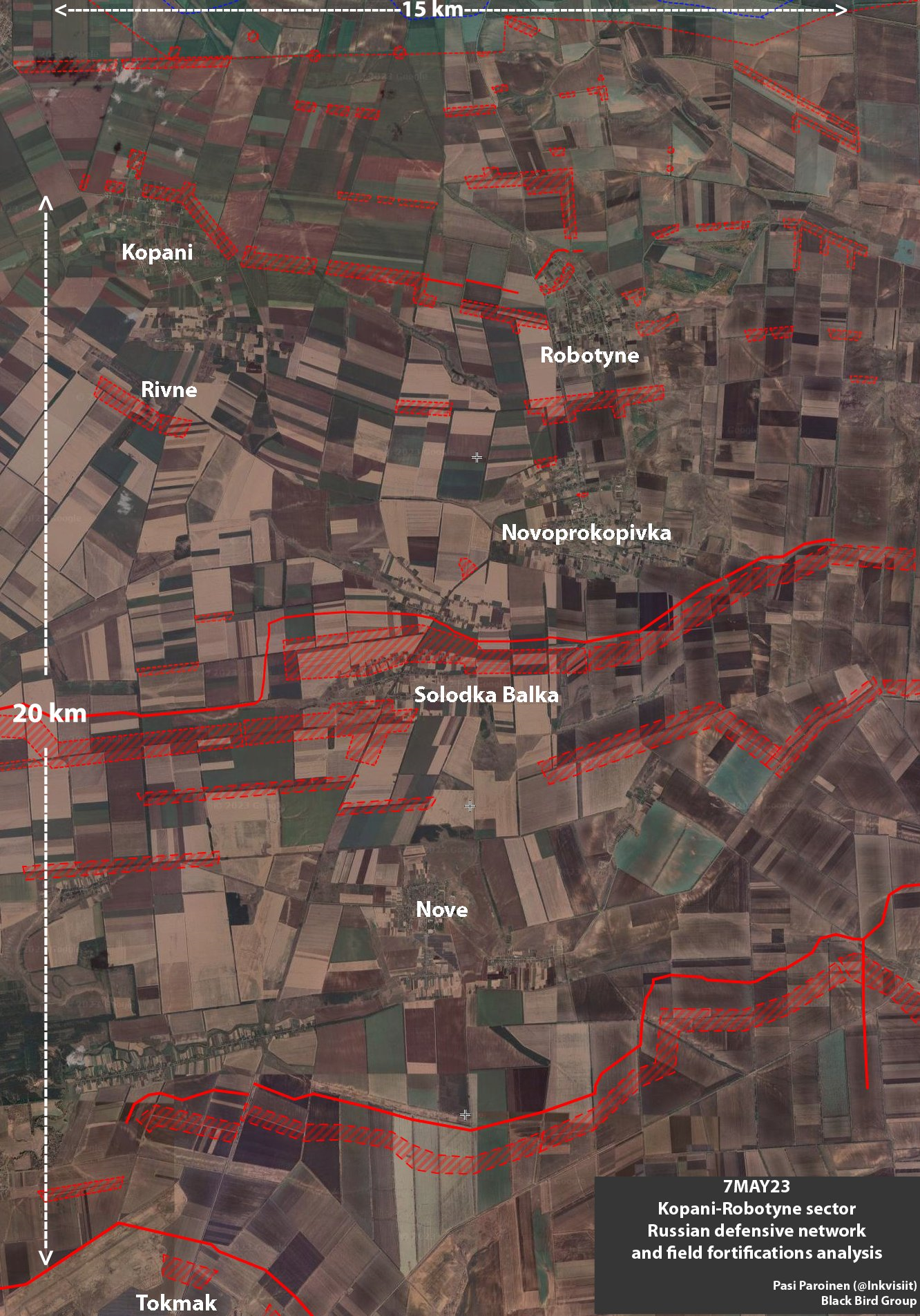

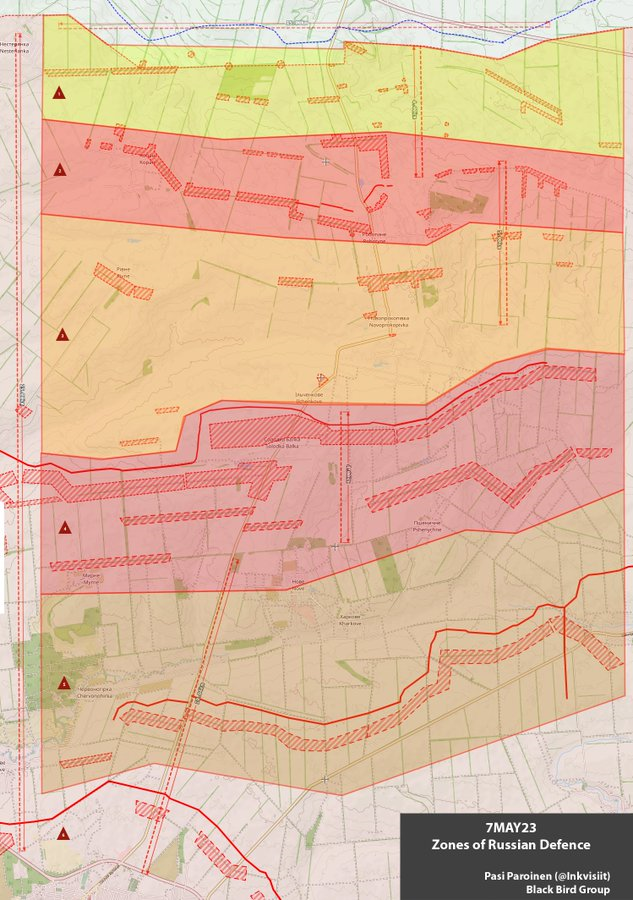

The following is a brief description of the segment of a single Russian defensive line north of the city of Tokmak in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, photographed by Airbus DS Pléiades Neo satellite and analyzed by Black Bird Group, a team of freelance OSINT analysts.

Since these images are from March, they are likely outdated and the defenses have most likely been reinforced.

The first zone, set back by up to four kilometers from the Russians’ forward positions, consists of squad and platoon level outposts and individual company strongholds.

The second zone is the first defensive line, several kilometers deep. There are company-scale trenches and strongpoints built in a continuous line, using natural terrain features to their advantage. This zone is continually being built up and improved. The villages of Kopani and Robotyne serve as the anchors of this specific position.

The third zone is up to five kilometers deep and contains positions for reserves and decoys, if Russia has them. The majority of Russia’s artillery and mechanized reserve will likely be maneuvering around this area. There are multiple shelters for vehicles and equipment.

The fourth zone is the main defensive line, a big network of multilayered trenches with anti-tank ditches, dragon’s teeth, and minefields to deter Ukrainian vehicles. This zone runs in a 3-4 kilometer deep continuous defensive belt along the front.

Behind this main line, there are reserve and fallback positions extending back towards another anti-tank trench running all around Tokmak, reinforced with strongpoints.

Can Russia man its defensive lines?

For their defensive positions to be effective, the Russian forces need enough troops, equipment, and fighting skill.

"The defenses have the potential to be formidable obstacles, but their utility almost entirely depends on them being supported by sufficient artillery and personnel. It remains unclear if the SGF (Southern Grouping of Forces) can currently muster these resources," the U.K. Defense Ministry has said.

The ISW has repeatedly observed that the Russians might find it problematic.

“For all the fortifications throughout the theater — Russian forces do not have the manpower to properly man these defensive fortifications,” said Hird. “It’s not like there are soldiers stacked up on all of these lines.”

She added that troops in many parts of the front are exhausted and arranged into odd, non-doctrinal formations.

For defenses to be effective, the defending side has to have substantial forces in reserve, being held back from the fortified positions. "Based on our understanding, this simply isn't the case," she said, with all of Russia's combined arms armies already committed.

However, some have cautioned against dismissing Russia’s preparations. Paroinen said that Russian forces could man the more forward defenses with lower quality troops, like mobilized conscripts, and keep more professional units in reserve, while pulling forces from other, quieter fronts, once they realize where Ukraine’s main attack is happening.

“The Russian military likely has the manpower and reserves to mount a stubborn defense, along with minefields and entrenchments,” wrote U.S. military analyst Michael Kofman. “This doesn't mean Ukraine can't break Russian lines, but past offensives suggest that Ukraine has challenges sustaining momentum after a breakthrough is achieved.”

The ability and spirit of the Russian conscripts and their equipment level are in question. It’s also unclear how mobile they will be when forced to fall back to defenses behind them. Russia has lost thousands of infantry vehicles and armored carriers in the war so far.

The other big issue with defensive fall-back maneuvers is the poor coordination in the Russian Armed Forces. Conducting an organized fighting retrograde of an entire brigade or regiment is not a skill Russian forces have exercised so far, Hird said.

“We have seen lots of small-scale tactical official operations all along the line,” she said. “The acumen it takes to do that is very different from what’s needed for large-scale defensive operations.”

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Igor Kossov, I hope you enjoyed reading our article.

I consider it a privilege to keep you informed about one of this century's greatest tragedies, Russia's ongoing invasion of Ukraine. With the help of my colleagues, I will continue to bring you in-depth insights into Ukraine's war effort, its international impacts, and the economic, social, and human cost of this war. But I cannot do it without your help. To support independent Ukrainian journalists, please consider becoming our patron. Thank you very much.