'Killzone' — Devastating scale of Russia's drone terror against Ukraine's civilians laid bare in new report

People cross a road in Nikopol, Ukraine, overlooking the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant on March 29, 2025. (Ed Ram / For The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Along a stretch of the southern front line on the Dnipro River, Ukraine’s largest, the civilian population is shrinking, active fighting is relatively low, and the death toll keeps rising.

A key driver of this disturbing trend is Russia’s increasing use of cheap, highly precise FPV drones. It’s a modern weapon that, in theory, should reduce civilian harm. Instead, a new report demonstrates how Russia has turned it into a tool of deliberate, calculated brutality.

In a new report called "Killzone: How Russian Drones Are Devastating the River Dnipro’s Right Bank," the human rights organization Truth Hounds documents the impact of short-range drones against civilians across the Lower Dnipro region — a roughly 400-kilometer (249-mile) stretch where civilian casualties from drone attacks are among the highest in Ukraine.

"These drones are extremely accurate because the operator sees everything. They guide the drone until the very moment of impact," said Vitaliy Poberezhnyi, a researcher at Truth Hounds, during a panel at Crimea Global on Nov. 17.

"Just as the world once debated landmines, we may soon need a drone convention."

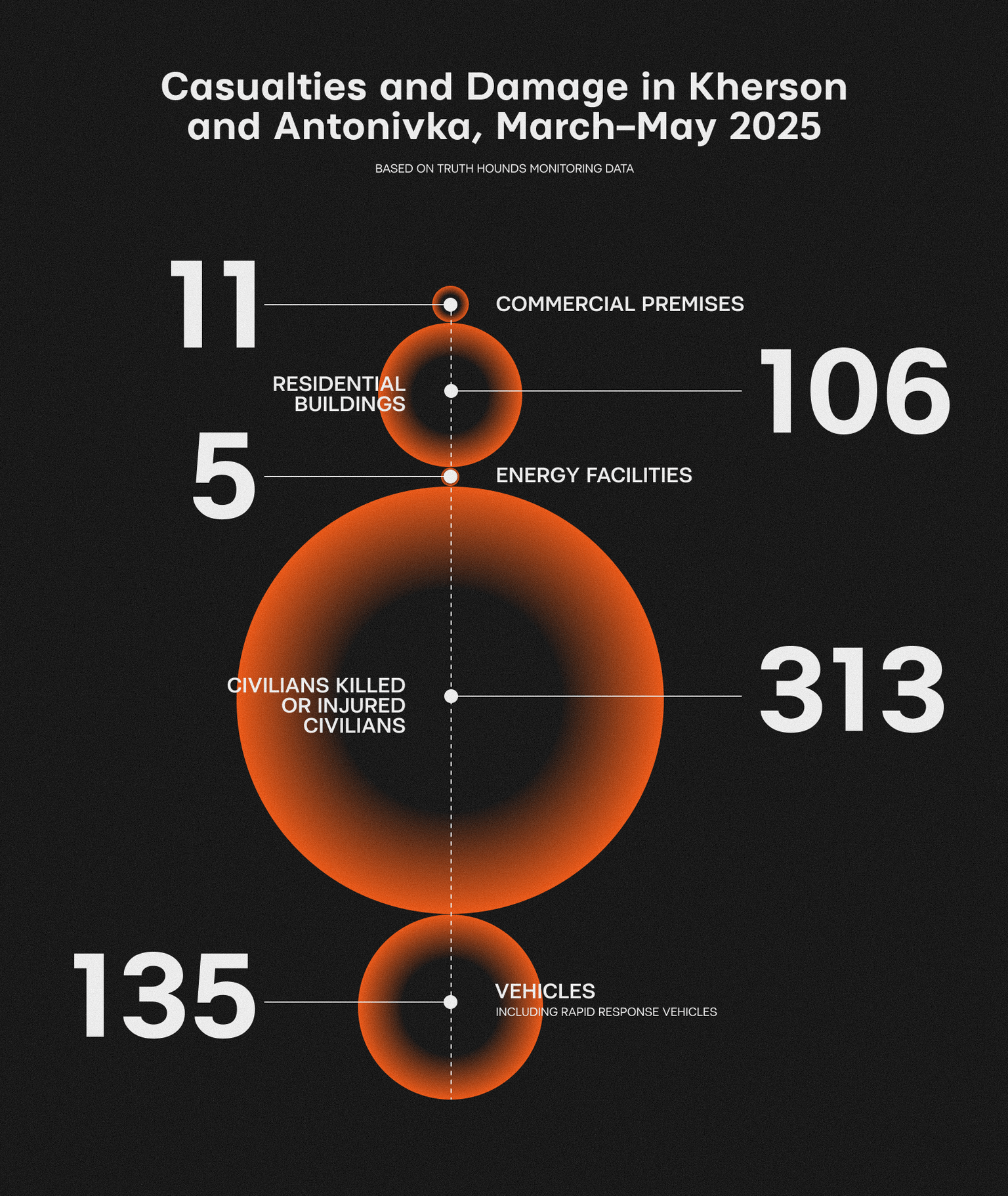

Their findings show how quickly the situation has escalated. In Kherson, Russian forces launched 600 to 700 drone attacks per week in March 2025. Between March and May alone, at least 313 civilians, 135 vehicles, including emergency service vehicles, and 106 residential buildings were hit.

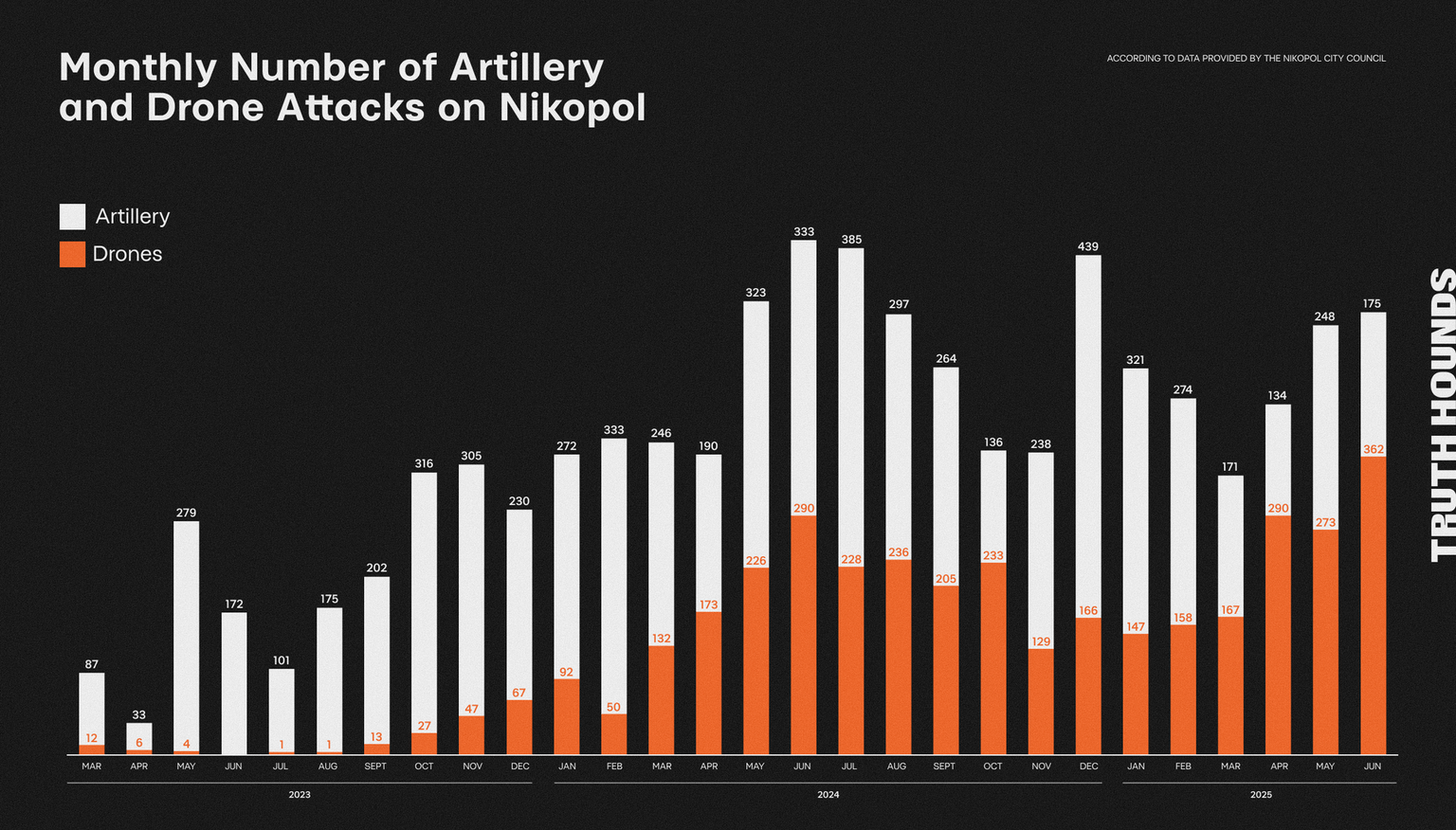

In Nikopol, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, separated from Russian-occupied territory only by the Dnipro River, drone use increased from zero in June 2023 to 290 strikes in June 2024 and 362 in June 2025.

According to Truth Hounds, these attacks are systematic. They form a consistent tactic: regular strikes on civilians, civilian cars, first responders, medics, and volunteers. The researchers say the pattern suggests not just disregard for the laws of war but, in many cases, deliberate targeting.

"They call everyone they attack ‘military.’ We see no intention to follow the rules of war. Attacks on firefighters and police, who have unique identification marks, are proof of that, " Poberezhnyi said.

Messages from Russian Telegram channels, including those linked to military units, reinforce this picture. They describe coastal areas as a "red zone," where any movement is considered a legitimate target, normalizing attacks on civilians.

Researchers argue this practice turns front-line settlements into places "without the right to life," where protecting civilians becomes irrelevant within Russia’s military narrative.

But the "red zone" is still home. Ukrainians remain there, living with drones constantly overhead. For more than two years, their daily routine has depended on luck, timing, and instinct.

Step outside — it’s a plan

"Every time you step outside, it’s a plan. Even driving from home to headquarters, I map it out — stick close to buildings, never open space," Serhiy Ivashchenko, head of the Antonivka community near Kherson, told the Kyiv Independent.

Fewer than 900 people remain out of a prewar population of over 10,000. The community sits just 200 meters from front line territory.

"You calculate every move. You rely on sound. That’s all we have left," he said.

While most Ukrainians monitor danger through mobile apps, that’s not possible in Antonivka. Russian forces destroyed the mobile internet network. People here rely on their hearing to sense incoming threats.

"I ran. The drone hit about five meters behind me."

"Fortunately, you can hear them," Ivashchenko says. "FPV drones make a very distinct buzzing sound. You have maybe 50 to 100 meters — sometimes just seconds — to react. If you’re in the open, you look for cover. Trees, basements, anything. Or you just hope to be lucky."

Ivashchenko survived his first drone attack in 2024.

"I had just stepped out of the car when I heard the buzz. The drone was already above the building. I took two steps toward a tree — and then it hit. It was a Mavic. Half the tree was blown apart. I was hit in the arm."

The second attack came later that same year.

"There had been a few explosions nearby. I waited, then went to check the damage. It was a school. Partially destroyed. One of the drones was still lying there, making a strange beeping noise. That’s what they do when they lose control."

"As I turned to leave, I heard the buzzing again. I tried to hide under a nearby awning — but the doors were locked. There was nowhere to go. I ran. The drone hit about five meters behind me. It went through my left leg. I got a blast injury."

All four schools and four kindergartens in the area have been destroyed or severely damaged. Children are gone, or so authorities hope. Rumors persist that some parents may be hiding children, afraid of mandatory evacuations ordered under Ukraine’s national security rules.

"If there’s a child still living here, they’re probably sitting in a basement. Ninety-nine percent of the buildings are destroyed. There are no schools. No kindergartens. Just ruins," Ivashchenko says.

Evacuating a child is a priority, but even that is dangerous.

"Just two days ago, a person was killed. Yesterday, police managed to reach the body, but their vehicle was attacked by two drones. The officers were wounded, but they survived."

Self-defense

After being wounded for the second time, Ivashchenko bought a drone detector and a shotgun.

"I needed a way to protect myself. After the second clash, I bought a gun. During the third attack, it saved my life," he said.

Across frontline communities like Antonivka, local residents have developed improvised layers of defense against FPV drone attacks. Ivashchenko describes a range of tactics: early warning systems using loudspeakers or radios, drone detection devices, anti-drone netting, mobile fire teams, and, in some cases, personal weapons.

Are civilians allowed to carry firearms for self-defense?

"Let me put it this way. Any means that help save lives — that’s a good thing. We are not aggressors. We have every right to protect our lives." he said.

While these measures are born out of survival, experts warn that the broader implications go far beyond Ukraine.

Hanna Shelest, head of the security programs at the Foreign Policy Council "Ukrainian Prism", argues that Russia’s mass use of FPV drones in Ukraine has turned a niche technology into a global concern.

"We’re entering uncharted territory — where civilian protection, asymmetric warfare, and cheap but lethal technology collide. Just as the world once debated landmines, we may soon need a drone convention," she told the Kyiv Independent.