Amid brutal Russian occupation, Kherson’s resistance continues through boycott, guerilla operations

Editor's Note: The names of some of the people in this story who live under Russian occupation have been changed due to security reasons.

One morning in early March, Iryna, 33, was frantically going through her closet looking for comfortable shoes. She knew she would have to walk to her destination since public transport had stopped running in the Russian-occupied city of Kherson.

But she was also in a hurry. She was heading to a rally against the forced Russian regime and she couldn't risk being late because of possible searches and interrogations.

Running out of time, she opted for heeled boots that she often wore to work, a school where she taught Ukrainian language and literature. Before leaving the apartment, she grabbed a Ukrainian flag from the shelf, folded it in half, and hid it under her coat.

After almost an hour of walking, she finally got to Kherson’s center, where thousands of residents gathered to participate in a peaceful protest. Iryna unfurled the flag and raised it above her head — she wanted the occupiers to see it and know they were not welcome.

"In the early days of occupation, I had no fear, no self-preservation instinct even," Iryna, whose name has been changed due to security reasons, recalls now. "My anger left no room for it.

Russian tanks rolled into Kherson, a regional capital in southern Ukraine, as well as neighboring towns and villages, from occupied Crimea in early March, about a week after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion on Feb. 24. Kherson Mayor Ihor Kolykhaiev then said that about 300 civilians and soldiers were killed during the days of intense fighting.

Iryna speaks of her city’s resistance with pride. "We showed that Kherson residents are brave and unconquered."

But no matter how brave, locals couldn’t continue to openly protest. Russian forces used tear gas and stun grenades against them, injuring protesters and spreading fear in the city. The last demonstration in Kherson was held in May, according to local journalist Kostiantyn Ryzhenko.

Russians have also further tightened the grip, kidnapping and jailing opponents to kill the resistance.

Yet it didn’t entirely vanish. It turned into sabotage or moved underground.

And when news of Ukraine’s unfolding counter-offensive operation to liberate the south started spreading in June, locals say the underground fight stepped up.

Read more: What would a Ukrainian counter-offensive in Kherson look like?

Persecution, abduction, torture

Russia occupied most of Kherson Oblast, including its regional capital, in the early days of the all-out war. Then it quickly moved to oppress the resistance and enforce Russian rule.

Five months later, the residents of the region’s occupied parts live in isolation. The city had a pre-invasion population of 290,000 people. According to Ukrainian authorities, up to 180,000 of them remained in the city, as of May.

According to locals interviewed by the Kyiv Independent, there is little access to medicine and other essential goods. People can’t access their money, since neither Ukrainian banks nor ATMs operate there.

The situation is so dire that there are now flea markets where people sell their stuff from the trunks of their cars to get some cash – a scene one woman described as “going back to the dashing nineties,” when the Soviet Union collapsed and Ukraine’s economy crashed.

But the worst part, many say, is that their hometown now feels like a prison, where saying even one wrong word could cost them.

Local journalist Ryzhenko says he rarely goes outside and stays the night in different locations every now and then so that Russian occupiers can’t easily find him.

"I cannot move around the city freely, or say that I am who I am out loud without risking being taken captive," he says.

Ryzhenko runs a Telegram chat for locals, where he keeps them informed on developments in the region and often shares statements by Ukrainian officials. His channel has become the main source of information for almost 40,000 people, he says, and the Russians do not like it.

Once Ryzhenko almost got caught, when Russian occupiers came to his apartment.

“I managed to escape just a few minutes before they entered my home as a neighbor warned me," the journalist says.

But many other residents weren’t lucky to escape.

According to ex-Prosecutor General Iryna Venediktova, Russian troops have kidnapped at least 457 people in Kherson Oblast as of July 7.

The Human Rights Watch (HRW) non-governmental organization said in a report that they had recorded 42 cases of forcible disappearance of civilians, with many of them being persecuted in the occupied south.

According to the nonprofit, locals told them about being tortured or witnessing torture by beating and, in some cases, electric shock. Some victims said they had broken bones and teeth, cuts, bruises, broken blood vessels, and severe burns.

"Russian forces have turned the occupied areas of southern Ukraine into an abyss of fear and wild lawlessness," Yulia Gorbunova, senior Ukraine researcher at Human Rights Watch, said.

The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) reported on July 25 that Russian occupiers had resumed the work of the Berkut riot police, known for its extreme brutality, to suppress and threaten the Ukrainian resistance in the occupied areas of Kherson Oblast.

“Victims are subjected to psychological pressure, violence, and death threats. The facts of abduction and torture of people have been recorded,” the agency said.

Ryzhenko says that in Kherson, the fate of most people who have been taken captive remains unknown.

According to multiple reports by Ukrainian and foreign intelligence agencies, Russia planned to conduct an illegal, staged referendum to annex Kherson Oblast, just like it did with the Crimean Peninsula in 2014. The first intelligence reports of such plans were published as early as April.

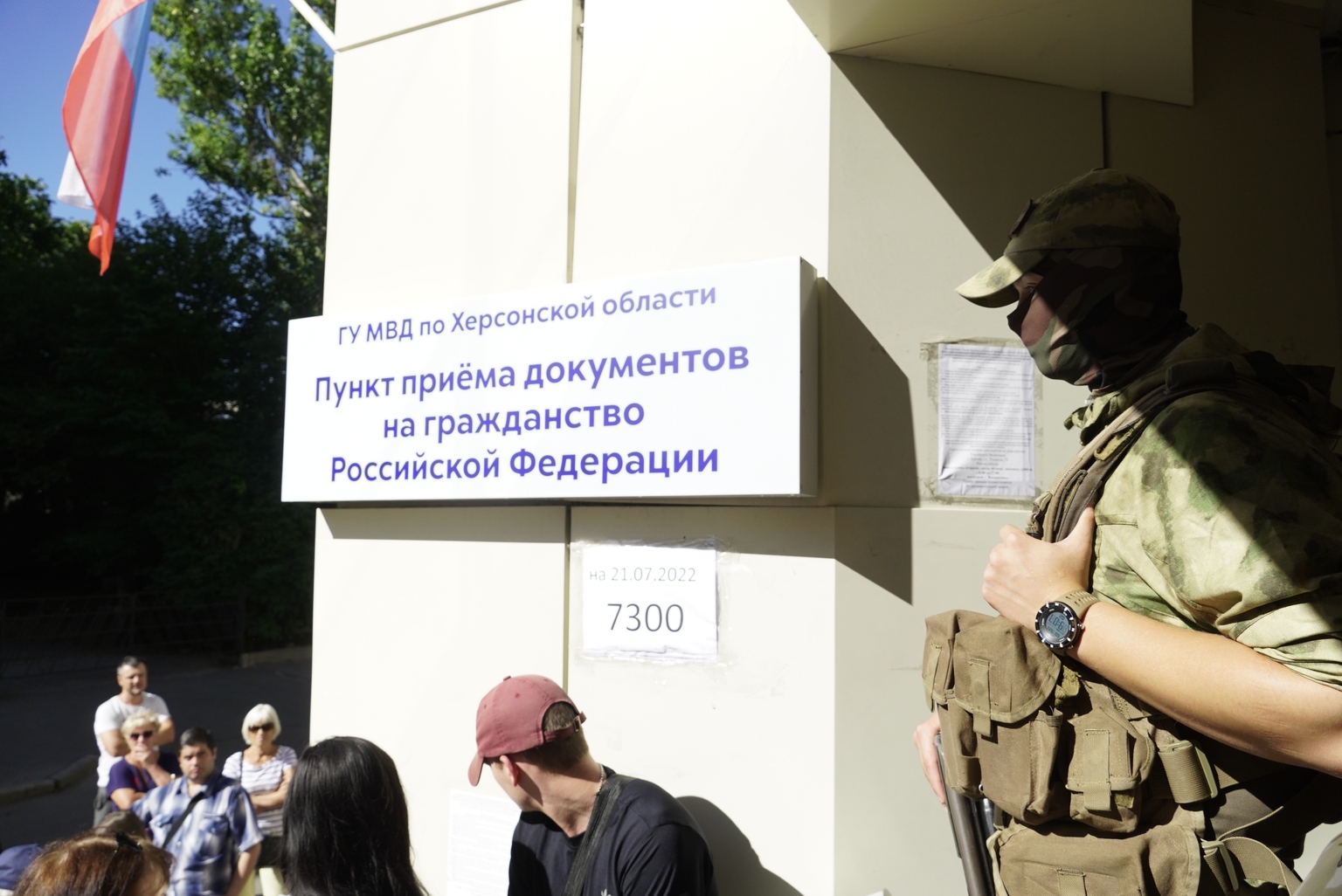

Russia claims that Kherson Oblast is "full-fledged Russian territory," as it continues to enforce the use of the Russian ruble and language, and forces locals into acquring a Russian passport. But it has so far failed to stage a referendum for its annexation. One of the reasons may be the continuous local resistance.

Read also: A front-line village in Kherson Oblast under heavy fire as local leadership flees

Sabotage

"Many locals, who cannot contribute more for various reasons, boycott basically everything Russian that is possible to boycott," Ryzhenko says.

Maryna, a 30-year-old pediatric dentist whose name has been changed due to security reasons, says that her clinic sabotages the occupiers' decree requiring enterprises to change documentation in accordance with Russian laws. She says the Russians set the deadline for July 7, but as none of the private clinics agreed to the terms, it was postponed to August 1.

The enforcement of the ruble is also mostly ignored by businesses in the city, the doctor says.

Maryna is also resisting the occupation on her own personal front by speaking exclusively in Ukrainian.

"Unfortunately, I grew up speaking Russian, but it's not pleasant to speak the same language as the soldiers that destroy my city and walk around it with machine guns as if they were at home," she told the Kyiv Independent.

She believes that if the Russians continue to hear the Ukrainian language everywhere, it will at least help weaken their morale.

"Once I even heard a Russian soldier saying 'thank you' in Ukrainian to a barista. He knows he isn't supposed to be here," Maryna says.

Underground fight

Local partisans have continuously caused inconveniences to Russian forces in Kherson.

People replace Russian flags on administration buildings with Ukrainian ones overnight and hang pro-Ukrainian posters on buildings, undermining the occupier's morale, according to a report by Ukraine’s National Resistance Center of the Special Operation Forces.

Sometimes more tangible actions are taken, presumably by Kherson guerrillas.

In late March, unknown people shot Pavlo Slobodchikov, who was an assistant to Russian-installed proxy in Kherson, Volodymyr Saldo.

Another attack happened on June 16, targeting the car of the pro-Russian head of a local prison Yevhen Soboliev. He survived the explosion but was hospitalized, as reported by Russian state-controlled news agency RIA Novosti. Russian troops blamed the attack on Ukrainian partisans.

Less than a week later, two more explosions were reported. One of them killed an alleged Russian collaborator Dmytro Savluchenko, according to an adviser to the governor of Kherson Oblast, Serhii Khlan.

The most recent explosion targeting two employees of the Russia-installed police happened on July 27. One of them was killed in the attack, which Ukraine’s Defense Intelligence Main Directorate believes to be the handiwork of the resistance movement.

There is no evidence that the attacks were linked or that the partisan movement in Kherson has a central command.

Ryzhenko says, however, that “an underground resistance movement in the city exists, but these people understandably hide their identity.”

In early July, it became known that President Volodymyr Zelensky had ordered the liberation of the south, including Kherson Oblast. By that time, Ukraine’s Armed Forces had already been making small but steady gains in the region.

Following the announcement, Deputy Prime Minister Iryna Vereshchuk urged the 450,000-500,000 residents remaining in Kherson Oblast to evacuate so that they are not used by Russian forces as “human shields.”

But for many locals, evacuating is not an option.

Evacuation may now only be possible through Russian territory, which pro-Ukrainian activists and journalists wouldn’t be able to pass without putting themselves at risk of being jailed, at best.

Others don't leave the oblast because they have no money to do so, or because they have elderly or disabled family members to look after, according to Ryzhenko.

The journalist says that those who could flee the occupied city had already done so long ago.

"And the others stay. And continue to resist as much as possible."

Listen to our podcast: Did the War End? Ep. 7: Fleeing Occupation in Kherson Oblast – A Story of Separation

____________________

Note from the author:

Hello! Thaisa Semenova here.

Thank you for reading this article. I hope you found it helpful and interesting. Since the early days of Russia's all-out war, I have been working almost non-stop to bring you quality journalism, mainly focusing on civilians affected by this aggression. For this story, I spoke with people who have been trapped in Russian occupation but found the courage and bravery to keep resisting. Our journalists have also shown those qualities, informing you about Russian aggression. By donating to the Kyiv Independent, and becoming our patron you can help us to continue writing stories like that.